Tonight, I’d like to take a few minutes to discuss something that has been in the back of my mind as I’ve wandered through business and marketing, through sales and slumps. It’s something that I’ve considered, but never explicitly mentioned as I wrote pieces like “A Word on Image, or A Failure of the Market and Marketers” and a biting insult for those on the outside.

Tonight, I’d like to take a few minutes to discuss something that has been in the back of my mind as I’ve wandered through business and marketing, through sales and slumps. It’s something that I’ve considered, but never explicitly mentioned as I wrote pieces like “A Word on Image, or A Failure of the Market and Marketers” and a biting insult for those on the outside.

We need to kill the term otaku.

Now, dear reader, put down the pitchforks and let me speak. “Otaku” is a derogatory term in its mother-tongue. These are folks that are seen to be so absorbed in their hobbies, so obsessed with what they do that they can hardly function. They are the folks that are trotted out in tabloids to sell copies, the social misfits that spend their waking hours playing erotic games and gawking at girls in maid cafes. They’re the ones that show affections to virtual idols, and who marry their video games. They are the undesirables that people prefer to ignore.

“Why is that important,” you ask? “It means something more here! It’s a badge of honor!”

If only that were true, dear reader.

Yes, the term “otaku” was adopted as a somewhat proud term in the west. For many years, it was used to refer to the core market – the customers that were knowledgeable of the medium. They were the sneezers in the market, the ones who would host viewing parties, and work on getting fan-subbed VHS copies of the hottest new shows, like Utena or Violinist of Hameln. They were the storytellers, and they were the drivers of a fledgling community.

“That doesn’t sound so bad!”

Honestly? It wasn’t at that point! The dynamic was a normal function of a growing market – the passionate would become the mouthpieces of a grass-roots, word of mouth movement.

“So why…?”

I’m glad you asked! Have you ever heard of the term “assimilation?”The process in which a group takes on the traits of a far larger collective? In the case of the term “otaku,” this process began to rear its head in the later half of the 1990s, as the term began to dilute, and came to mean “huge fan” among the sub-culture. From 1997 to 1999, the use of the term spiked.

Going forward, we began to see the term’s meaning degrade. As 2000 flowed into 2005, we saw the term fracture within the anime community, as a new meaning began to emerge in the greater market. In the anime community, a second term began to associate with the word. While there were many that continued to use the term as a positive, it also adopted the meaning of “fanboy.”

Outside of the community, thanks to numerous articles by publications like Time and the New York Times, people began associating the term “otaku” with a more whimsical sort of sight. Stories of costumed super-fans and geeky youngsters began to color the dialogue. They were seen as a curious, if harmless minority in a larger market. And, of course, we had the stereotype of the “basement dweller” take prominence in this era. During this time, the term would conjure images of an overweight thirty-something, whose ratty anime shirt showed the scars of the last battle with a McChicken. This sad stereotype would spend his days watching “those crazy Japanese cartoons” day in and day out, as the concept of a shower eludes him.

The descent continued further, as we pushed toward modern day. As stories such as the “Otaku Kidnapper” made headlines, the market associated the term “otaku” negatively. They were suddenly anti-social, sociopathic mega-fans that had no qualms with snatching people off the streets. They were perverts, pedophiles, and kidnappers. Within the anime community, the term “otaku” continued to hold a dual meaning. The “eager fan” definition still has fairly wide usage. However, it is being replaced, by and large, to describe the “Wapanese,” those so enamored with the idea of Japan, and the notion that the country is somehow “better” than America. These are the folks that use broken Japanese phrases in place of an English equivalent, and they are the ones that will wear Naruto headbands year-round while talking about how Japan would worship them for enjoying anime.

“So it’s negative already. Your point?”

It’s negative to a point. In the greater market, the term is toxic. People associate the term with perverts, rapists, and kidnappers, which pushes them away from the subculture in which the term originated as a side-effect.

In the subculture, though, there are still many that view the term as a positive. They wear it as a “badge of honor,” of sorts as they are blissfully unaware of how much of a black mark it is. This group will argue and fight about how such generalizations are “wrong,” and how they don’t need the approval of “the masses.” They huddle together and comfort each other, saying how they are “being themselves,” and that everybody else is in the wrong. It’s their word, and only they can say what it “really” means.

Unfortunately, language doesn’t work that way. If it did, certain hurtful slurs would still be merely innocent terms for sticks, or strange occurrences.

If we, as a whole, hope to expand the anime market into a greater audience, we need to begin shedding the baggage that haunts the niche, from the toxic people, to the toxic terms. While it’s easy to step away from the militant geeks and the creepers, creating an image that won’t repel the greater market will take far more work.

Killing the “O” word would be an ideal first step, as it would signify not only a change in attitude, but a change in focus for the anime market. After all, there are words that people are simply conditioned to respond to in various way. Terms like “aficionado” or “enthusiast” garner a far more positive reaction than “geek” or “fan.”

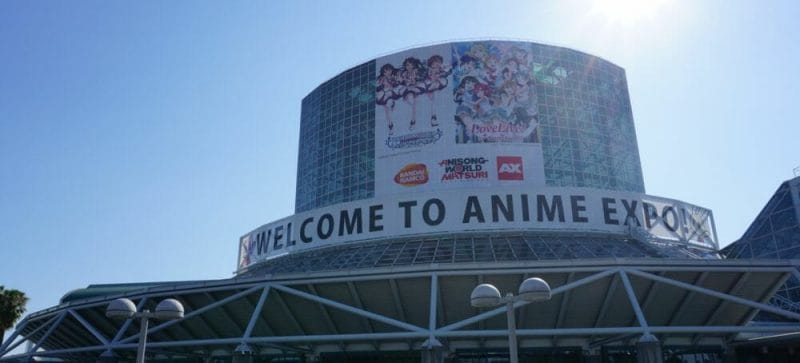

While this does little for people who scream games of “Marco Polo” in the halls of the Hynes Convention Center, it certainly doesn’t need to, either. Instead, rather than pander, we need to embrace. We need to begin to shift focus on what works – the many (and I mean many) positive things that come from the community. We’re a large, diverse group that has individuals that range from the aspiring youth, to the distinguished professional. We’ve organized massive charity drives and blood drives. We’ve donated thousands to the relief efforts in Tohoku, and we’ve gone above and beyond on many dozens of occasions. It’s about time that we “cash in” on this, so to speak. We need to begin to leverage our positives – our giving natures, our willingness to go above and beyond for those around us, and the generally welcoming sense of community that flows through the subculture. We need to highlight the passion in artists and cosplayers, and in the various clubs across the country.

After all – once we begin respecting our own market, we’ll begin earning respect from others, and with this respect comes a curiosity that can finally be satisfied without fear of stigma.