Over the past year or so, you’ve heard me talking about disruptive products. More specifically, you’ve heard me describe them as “crappy products for crappy customers.” While I’ve gone into detail about the “crappy products” end of things, I’ve rarely delved into the notion of a “crappy customer.”

In the business world, customers are often referred to as points of data on a chart. At the top of the chart is the “best customers.” These are the loyalists, the fanboys, the “hardcores” that will line up on day one to buy a product sight unseen. They’re the ones who will camp out at midnight for every big title. They’ll watch a series via the company’s web portal, then fork over $60 for the boxed set. They are the ones that’ll fill the forums and social media outlets with praise and complaints. They are the ones who will plan their schedules around releases, then bitch ceaselessly about everything that comes out as they continue to open their wallets.

On the opposite side of the spectrum is what I’ve been referring to as “crappy customers.” Businesses give much nicer, more friendly names to this group, like “casual buyers”, “transient customers”, and “outer markets.” They’re the group that doesn’t usually go out of their way to buy a product. Crappy customers usually buy a product only when it appeals to their needs or their interests. They don’t care if a product isn’t the most advanced on the market, but they do care that it’s accessible, usable, and fills a need they have. They’re not going to hunt a product down, and they’re not going to spend months obsessing over minutiae, nor are they going to spend hours trying to figure out how certain aspects of products work. More than anything, if they’re dissatisfied with the product, this group will often just stop buying and move on to their next interest.

On a superficial level, then, it’s easy to see where businesses will often side. Their most loyal customers are, without a doubt, the easiest money they can earn. This group will do everything for them, from buying the product to hyping it up amongst themselves and their like-minded peers, and even telling businesses exactly how to tailor things to their needs. They’re the ones who will double, and sometimes triple dip on their favorite properties, and they’ll go out of their way to show that they love a property in very public ways. In a niche market, this easy money is hard to ignore. Higher-ups see that this group turns out in spades when they want something. And, because of this, whether it’s from overt pressure from above or by subconscious action, businesses will align toward these proven revenue centers and do everything they can to make the group happy.

On a superficial level, then, it’s easy to see where businesses will often side. Their most loyal customers are, without a doubt, the easiest money they can earn. This group will do everything for them, from buying the product to hyping it up amongst themselves and their like-minded peers, and even telling businesses exactly how to tailor things to their needs. They’re the ones who will double, and sometimes triple dip on their favorite properties, and they’ll go out of their way to show that they love a property in very public ways. In a niche market, this easy money is hard to ignore. Higher-ups see that this group turns out in spades when they want something. And, because of this, whether it’s from overt pressure from above or by subconscious action, businesses will align toward these proven revenue centers and do everything they can to make the group happy.

However, this does create a somewhat difficult atmosphere for expansion.

By catering primarily to the best customers, you begin to attract those who will impose their own tastes, no matter how off-putting, on a company’s habits. Say, for example, this market suddenly develops an appetite for, oh, I don’t know, shows that revolve around magical princesses that solve their problems with pillow fights. Now, you and I both know that there is very little market for such a license, were it to exist. However, that’s not the point we’re trying to make.

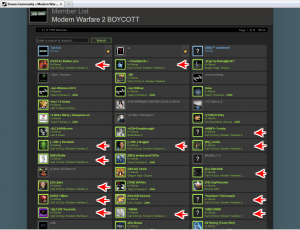

In the case that this group knows their status in the hierarchy as the so-called “golden geese”, they’ll do everything they can to try to get what they want – petitions, forum lobbying, social media harassment… anything that could possibly garner the attention of the company (or a sympathetic segment of the press that would give legitimacy to their crusade). This would leave the company with two options: to relent and give the group what they want, or to dismiss the claims with the explanation that the average customer doesn’t want shows about pillow fighting princesses. In the latter case, there would be some fallout, calls that ‘Company X hates their customers” and boycott threats. While some would carry through, the vast majority would just fold in on their threats and line up for the next product in the pipeline.

The former case, though, is where things would get interesting. If the company relents and gives in to their “best customers'” demands, it emboldens this group. This batch of customers realizes that they are the favorites of the company, and that they can make absurd demands to get what they want even at the expense of the greater well-being of the company that delivers the products they consume. This, in turn, attracts the worst elements of the bunch – those with no lives, who will ride in on the wave of euphoria to stake their places in the customer-base. They will be the ones that lead drives to products with smaller and smaller appeal, and drown out any dissent. They’re the group that will boast about how they got company Y to do what they desire, and that anybody who disagrees is wrong. Discussions are stifled, and the market continues to shrink until the company itself takes corrective action.

“This sounds a bit far-fetched.”

I’ll agree that it sounds a bit “out there”, reader. However, we have seen such behavior arise over the years, especially in gaming communities. In Nintendo game Super Smash Bros., we have the “tournament scene” that insists that games be played only on Final Destination, with no items, with certain pre-approved characters. In World of Warcraft, we have people who will grind for countless hours to get a rare mount or item, to lord it over other users, and use the item as a claim to power in guilds (“proof” of one’s mettle, you could say). It’s an observable phenomenon that can, and does often repeat in communities where the divide between core consumer and infrequent buyers to represent itself.

“So how does this tie into crappy customers?”

Well, dear reader, to begin, focusing on the crappy customer bypasses the potential pitfall this outcome entirely. By focusing on the outer market, the power structure isn’t allowed to form, and these vocal customers remain just that. They’ll complain, they’ll argue, and they’ll scream about how the product is being “dragged downhill” or “dumbed down”, but these people will usually purchase the product, if they don’t retreat upmarket to more advanced and expensive products.

Instead, focusing on crappier customers presents a brand new challenge. Crappy customers know what they want, and they know what they like. However, they have to be able to see how certain products appeal to them. In the anime world, this is easier said than done. While there are titles that can attract the “crappy customer” set, like Naruto, Dragon Ball, and Cowboy Bebop, these products are few, far between, and at the mercy of the shows’ Japanese creators. And, unfortunately, what works in Japan, doesn’t necessarily translate to success in the west – phenomenons like K-On! and Lucky Star went on to disappointing American sales, for example. So, in addition to a keen eye and proper promotion, a degree of luck is needed, in hopes that a company will release something that appeals to more than just hardcore fans or kids.

But, of course, that’s what makes the anime industry to intriguing. There’s always the gamble, always the uncertainty and the romance of the “dice roll” on a big title. There’s room for experimentation, and the occasional misstep, and there appears to be just enough of an interaction with all markets to prevent the nightmare scenarios from kicking into gear.