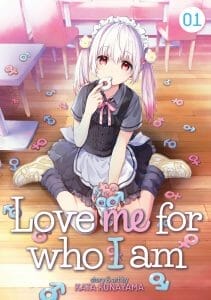

Newly released and translated into English, manga Love Me For Who I am (Japanese: Fukakai na Boku no Subete o or FukaBoku for short) from Seven Seas Entertainment is artist Konayama Kata’s attempt to explore the complexity of gender and gender identity through the eyes of a group of high school students working at a maid café. While on first inspection the café appears to have the theme of “cross-dressing boys,” it soon becomes obvious that such a label is highly inaccurate and very few of the characters identify as boys, specifically the central character, Mogumo who struggles to articulate an identity neither boy nor girl.

Newly released and translated into English, manga Love Me For Who I am (Japanese: Fukakai na Boku no Subete o or FukaBoku for short) from Seven Seas Entertainment is artist Konayama Kata’s attempt to explore the complexity of gender and gender identity through the eyes of a group of high school students working at a maid café. While on first inspection the café appears to have the theme of “cross-dressing boys,” it soon becomes obvious that such a label is highly inaccurate and very few of the characters identify as boys, specifically the central character, Mogumo who struggles to articulate an identity neither boy nor girl.

In considering FukaBoku, I wish to give a disclaimer that I previously read the work in the original Japanese. Therefore, unlike many reviewers, I have had a great deal of time to get to know these characters and think deeply about their identities. Although I have read carefully through Amber Tamosaitis’ translation, I’ll give my own thoughts on how I interpreted the original Japanese work, as it pertains to how the characters identify.

It’s worth noting that I have lived in Japan for a fairly long time now as a gender variant person, and as such, I would say I have actual, lived experiences of how these terms operate, and these experiences color but also support my own “translations.” However, I’m not a professional translator. Just someone very familiar with the terms I am about to discuss as they exist in my daily life, and as someone who speaks Japanese, albeit non-natively, on a daily basis. Also, I will state plainly: translation is an art. It is also a skill, but there are many ways to consider the original language and parlay it (word choice here intentional) into the target second language.

What makes translation so difficult in FukaBoku is the fact Japanese gender variant vocabulary is incredibly fluid. Tamosaitis includes a very necessary translator’s note about the term “otokonoko,” and how the character of Mei uses it in her discussions with the non-binary Mogumo in a much narrower way than it is often utilized across the Japanese queer community.

The kanji choice for the word literally means “male daughter” and works as a way of talking about sex and gender as two distinct concepts. It’s also a pun, because the homonym “otokonoko” means “boy,” or more literally, “male child.” The use of the kanji character for daughter (“musume”) is a way of drawing the distinction between a male physicality and feminine gender identity. In English, we can say “she was assigned male at birth but is a girl” now. Likewise, even more bluntly (and perhaps inappropriately or offensively, depending on the person) we can say, and be grammatically consistent and conceptually distinct, “she is male, but she is also a girl.” Trying to say that in Japanese is more difficult, because “otoko” can be “man/boy” or “male.” The same can be said of every compound of “otoko” and another kanji, like “danshi” or “dansei.” Therefore, the use of the “ko” kanji meaning “daughter” serves that same conceptual function.

Although, the term “otokonoko” is much broader than “binary trans girl.” While it applies to those assigned male at birth, it’s much closer to the English idea in the concept of “transgender” as an umbrella term. It can mean anything from very femme gay boys, to trans girls, and really anyone who is anywhere on the line between them. It can include crossdressers to a degree, though I’m of the opinion that there is a distinction between “otokonoko” and “josou;” the latter term referring to crossdressing.

The “daughter” aspect is wrapped up more in gender presentation and gender expression and less in gender identity, but binary trans girls definitely fall under it as well—unless, of course, a particular trans girl or non-binary individual rejects it due to the “otoko” root. There are most certainly those who define themselves as “toranzu shoujo” or “toranzu josei”—trans girl, trans woman. They reject the term “otokonoko” outright. None of Love Me For Who I Am’s characters fall into this category except Mogumo, and we’ll discuss Mogumo last.

So, let’s consider the main part of our maid café cast. It’s difficult to even articulate, without making value judgements, how this should proceed. Saying “least complicated to most complicated” or “least interesting to most interesting” isn’t correct, nor is it appropriate. Perhaps “requires the least explanation to the most explanation” might be the best way to go.

Mogumo requires the most discussion, and also rejects the term “otokonoko.” Who requires the least amount of discussion?

Probably Ten-chan. If “otokonoko” is a transgender spectrum, Ten is probably on the most, er, “cisgender” side of it. Ten is a crossdresser, whose interest is cosplay by his own admission. I would say, generally speaking, “josou” is probably a more accurate term for Ten. This doesn’t mean I consider Ten’s gender variance to be invalid, though! Still, I think it’s important to note that Ten’s crossdressing is part-time, a performance, and it doesn’t define his gender. We should respect Ten’s cis-ness by not ascribing to him a gender identity he does not have due solely to his cross-dressing choices. That, too, would be inappropriate and unfair.

Mei does require a fair bit of discussion, but only because she has to work up the courage, with the help of the others, to really articulate her gender identity. Mei seems very clearly to be what we would call a “binary trans girl” in English. Mei’s reactions sound a lot like the discussion about identity trans women might have had as recently as possibly ten to fifteen years ago in English, but certainly going back much further.

Her attachment to “otokonoko” and attempt to define it narrowly, to which Tamosaitis rightly draws our attention, reminds me somewhat of living th rough the “transsexual as a noun” debate. “Reality won’t just let me say ‘I’m a girl,’ so I’ll say this term applies to boys who wished they’d been girls, even though I guess they have to accept they’re not!”

rough the “transsexual as a noun” debate. “Reality won’t just let me say ‘I’m a girl,’ so I’ll say this term applies to boys who wished they’d been girls, even though I guess they have to accept they’re not!”

Mei is clearly afraid she’ll be so utterly rejected if she claims the gender of “female/girl” outright, with no compromise, that she not only places herself within “otokonoko” with its “otoko” root, she defends it from broader use beyond her own situation and those with experiences like hers. By no means is this a 1:1 comparison, obviously, but there is a reason why “transgender,” or just “trans” as an adjective has almost completely replaced “transsexual,” and noun usage is generally considered unacceptable or offensive. Mei’s ability to take ownership of an identity she has absolutely always had, but been afraid to claim for fear of rejection, comes surprisingly early in the series.

My favorite character is actually Suzu, an example of movement from “ungendered” to “gendered.” A poor reading of Suzu’s character would be that Suzu is a femme, but cisgender and binary, gay boy, in order to contrast Suzu with Mei or Mogumo. I think this does a great disservice to Suzu, though. Suzu does use “ore” as a personal pronoun (as compared to Mei, who uses “boku” (kanji) or Mogumo, who uses “boku” (kana) ), which is traditionally viewed as being overtly masculine. This isn’t as important an indicator as it might at first appear, though, because Suzu’s personality and presentation (aside from school uniform when at school) is really feminine, even overtly “girly,” and not really that different inside or outside the Café Question. Only Suzu’s fear of queerphobia keeps Suzu somewhat muted.

So, how do we draw a conclusion about Suzu’s gender?

Well, what does Suzu say about Suzu? My own translation, rough as it was, would have been something like, “I would say my gender is ‘wearer of cute clothes,’” said humorously. More seriously, Suzu follows it up with (again my rough translation), “The truth is that I started to become the girl that the person I liked likes. The fun type, I guess.” I’d be curious to know why my translation is so much stronger about gender than Tamosaitis’ “I wanted to be the girl that the guy I liked was into…”

I think we’re both headed in the same direction, but I read “Suzu’s Case” as Suzu having turned a significant identity awareness corner. Suzu hadn’t really contemplated gender, but after the influence of her boyfriend, her gender identity began to exist. Unlike Mei, Suzu didn’t have any strong attachment to a gender. She wasn’t a boy, she just put on “boyness,” almost as if it was part of her school uniform. It was expected, and it was no big deal to go with the flow.

Until it suddenly became a big deal. Only within the context of her romantic relationship did she come to have a gender… And that gender is “girl.” This is a completely valid narrative, often occluded by the much more known narrative of “I always knew” or “I always felt,” as we have with Mei.

This doesn’t mean Suzu’s identity is complete. I’m certainly looking forward to seeing how Suzu continues to grow into “becoming a girl,” and if her willingness to show her gender expands beyond her boyfriend, her friends, and the café. Despite her awareness coming from dressing up for her boyfriend, Suzu’s gender is not a costume. Ironically, her “boyness” is and was.

Which leads us to Mogumo, a character who outright rejects “otokonoko,” even if others might apply it to them. As the central character, the difference between Mogumo and the others is pretty obvious. While all characters represent gender variance, from Ten to Suzu, they’re all binary. Even Suzu, who is moving towards a clear binary identity, even if she started without a conceptualization of gendered self, was not non-binary in the way Mogumo is non-binary. Mogumo is strongly identified as neither a boy nor a girl, and they reject “otokonoko” because the root indicates an existence or reality starting from or within “boy.” I have argued here that neither Mei nor Suzu were ever boys, but their own circumstances mean they simply do not find “otokonoko” invalidating the way that Mogumo does.

Mogumo’s presentation fits in the box we as a cisheteronormative society typically label “feminine” or “girly” or, until very recently, just labeled “girl.” Mogumo’s use of “boku (kana)” itself likely references the shift of “boku” from a male pronoun to a more gender-neutral pronoun, with the increase of female narrators and young women using it. In comparison, Mei’s use of “boku (kanji)” might reference the recognition by Mei of her struggle to separate herself from the “reality” of being assigned “male” at birth.

We can even put Mogumo’s expression in this box, though this is difficult to glean just from static pictures, despite how talented Konayama is in showing tension and movement. But gender as a whole requires the confluence of presentation, expression, and identity. And Mogumo’s identity is neither boy nor girl. Mogumo’s identity is Mogumo. Which means that Mogumo’s presentation and expression themselves perhaps should be referred to as “Mogumoteki” (Mogumo-ish), rather than feminine or girly.

This is the major way in which Mogumo is different from all of their co-workers, and also the factor which makes it difficult to understand Mogumo’s feelings. Ten may be a boy, but he wouldn’t question that his cosplay of girl characters means presenting girlishly, at least before meeting Mogumo. Mei is a binary trans girl and actively wants to demonstrate the gender identity she has always had through choosing a presentation which identifies the box in which she already exists. Suzu has found her gender by putting that same box on herself in the context of her relationship with her boyfriend, and finding it seems to fit and the more she explores it, the more comfortable she is.

It’s easy to understand how Mogumo’s identity might, at first glance, contradict the identities of the others, especially Mei and Suzu. It also becomes perfectly understandable why Mei reacts the way she does. Yet on closer inspection, the point of Love Me For Who I Am seems quite clearly to be when it comes to gender, two simultaneously opposing views might not actually be in conflict at all. It’s absolutely crucial that Ten be allowed his hobby without losing his box, Mei’s box be recognized as existing, and Suzu has the freedom to keep exploring her new box… while it is similarly crucial that Mogumo doesn’t get put into a box at all.

Boxes matter very much indeed, you see, except for when they don’t matter at all.

A huge thanks to Seven Seas for providing us with a review copy!