In the world of video games, it’s not uncommon for the topic to shift to individual creators and the impacts their works have made upon the world. Though many of today’s most influential titles are collaborative works between many different hands and perspectives, people tend to place an oversized emphasis on the singular creator figure. As such, Hideo Kojima is accepted as the creator of the Metal Gear Solid franchise. Warren Spector dreamed up Deus Ex, Resident Evil sprung from Shinji Mikami’s imagination, and so on.

Though they didn’t work alone, these respected creators have left indelible marks upon the industry at large. Beyond the games they worked on, these individuals have made an impact on the markets, the companies, and even the very people that they’ve come in contact with.

In the case of Shinji Mikami, specifically, it’s hard to deny that there are few who made a greater impact on the Japanese gaming landscape. Mikami began his career in 1990, joining Capcom shortly after a meet-and-greet for new university graduates. He cut his teeth with the Game Boy quiz title Capcom Quiz: Hatena no Daibōken, before lending his talents to surprisingly well-received licensed games like Goof Troop and Aladdin.

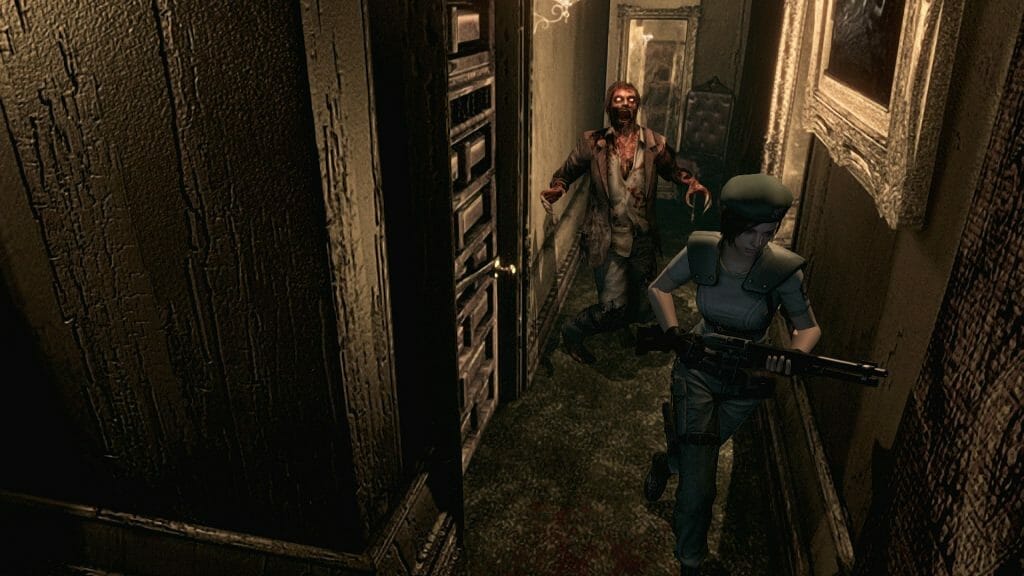

In 1993, Mikami sought to make his mark with something more ambitious. Following a mandate from Sweet Home director Tokuro Fujiwara, Mikami and the Capcom Osaka studio were challenged to make a new game using the experimental horror RPG’s gameplay systems. In 1996, the world would be introduced to the end result of this initiative: the title that would cement the identity of the survival horror genre known as Resident Evil. The title became an instant classic, selling millions of copies worldwide and solidifying the survival horror genre as it’s known today. The genre would again be revolutionized a decade later, when Mikami took the director’s chair to helm celebrated classic Resident Evil 4 in 2005.

This side of his story has been told time and time again, to the point that it’s treated as common knowledge among many fans. What you may not realize is that his clout in Capcom benefited other designers, and he actively encouraged creative risks. Just ask Hideki Kamiya, one of Platinum Games’ cofounders and star directors. He was entrusted with the task of directing Resident Evil 2, leaving his own stamp on the series when it launched in 1998. Moreover, he was also nearly handed the reins for Resident Evil 4. He was actually tasked with directing the title in its earliest stages, though the game’s convoluted development cycle saw the horror classic taking radically new forms as it went along.

Kamiya’s version revolved around a guy with superhuman powers on a mission to learn his past. The game traded the horror elements the series was known for, instead opting for fast-paced hack-and-slash madness accented by superhuman feats. Mikami realized this concept was a bit too different from what the Resident Evil series was at this point. Instead of just tossing the idea out, though, he figured that Kamiya should turn this concept into an original game, and encouraged him to flesh it out from there.

The end result was Devil May Cry, where the concept of a character action game was first introduced, and later polished by Hideaki Itsuno and his team with Devil May Cry 3: Dante’s Awakening. Kamiya’s project completely redefined what a 3D action game could be, and forced the entire industry to alter their views on how to handle 3D action. Before all of this, before Capcom let him make what he wanted to make and he continued to do so with Platinum Games, Kamiya was just one of the Resident Evil team. He may never have received his shot to direct games like Bayonetta, The Wonderful 101, and Okami were it not for Mikami’s ability to see something special in the young director’s strange ideas for a new Resident Evil game.

That’s to say nothing of the time when Mikami met with a quirky and inventive developer (and former gravekeeper) named Goichi Suda, better known as SUDA 51. Suda was a former designer from Human Entertainment, having worked on a gaggle of experimental Japan-only games. After leaving Human Entertainment to pursue direction, he formed Grasshopper Manufacture in 1998. Truth be told, it’s likely that Suda still would have had a major impact on the gaming medium even if he never met Shinji Mikami. The violent and bizarre Moonlight Syndrome, for example, is listed as a major inspiration by the creators of Danganronpa. Still, it’s hard to imagine that he would still be actively working in the industry if he hadn’t partnered with Mikami to create Killer7.

In late 2002, Capcom was trying to show major support for Nintendo’s then-new Gamecube. As a show of solidarity, the House that Ryu Built unveiled the Capcom Five initiative: a series of five exclusives that would be unlike anything the gaming world had ever seen. The project deserves its own article, if just for the fact only four actually released, but the important part here is that Killer7 was one of these games. It was a truly bizarre hybrid of rail shooter and survival horror, mashed into an absurd story that often teetered between political commentary and nightmare sequences. Suda directed and wrote for the project and fleshed the concept out with Mikami, who offered guidance and assistance alongside co-writer duties.

Despite its low sales, Killer7’s 2005 release was a flashpoint, in which the western world learned the name SUDA 51. That foot in the door would later prove to be the event that would save Grasshopper Manufacture. In 2007, the studio released No More Heroes as a Wii exclusive. The title would be a retail failure in its home country, selling just 10,000 copies on its first day, one of the worst game launches in the history of Japanese gaming. As a silver lining, the game would later receive a western release, becoming a cult favorite among players worldwide, selling more than 360,000 units in North America and Europe. Though he is greatly respected as an auteur director today, Goichi Suda wouldn’t have had the opportunity to even continue working within the gaming industry, had Mikami not taken note of his talents. Suda was granted an opportunity to introduce himself to the world through Killer7, a blessing that he didn’t dare squander.

Arguably Mikami’s most concrete impact, though, came from the founding of Tango Gameworks. This was the studio that Mikami founded in 2010, and one he worked with to direct his latest game – The Evil Within.

Though reception to the first The Evil Within was mixed, it was a completely different story for its sequel, the aptly-titled The Evil Within 2. Mikami didn’t direct this 2017 horror title. Instead, it was helmed by a newbie developer named John Johanas, who worked as a visual effect specialist on the first game. Under Johanas’ direction, the project took a completely different tack, opening the world and introducing more in-depth mechanics like crafting, not to mention more engaging writing and strong character arcs. Mikami took a backseat supervisor role to help guide the new talent he gathered, and the vision was theirs to form. As a result, the final product was received far more warmly than its predecessor.

While it’s sad to see Mikami shift to the background as his career continues, one has to respect the impact he continues to have upon those he works with. Even now, he works behind the scenes to help younger developers have their shot to create the games they want to make. It makes one wonder just how many people Mikami impacted through his wider influence. This question becomes particularly relevant over the course of Goichi Suda’s Travis Strikes Again: No More Heroes.

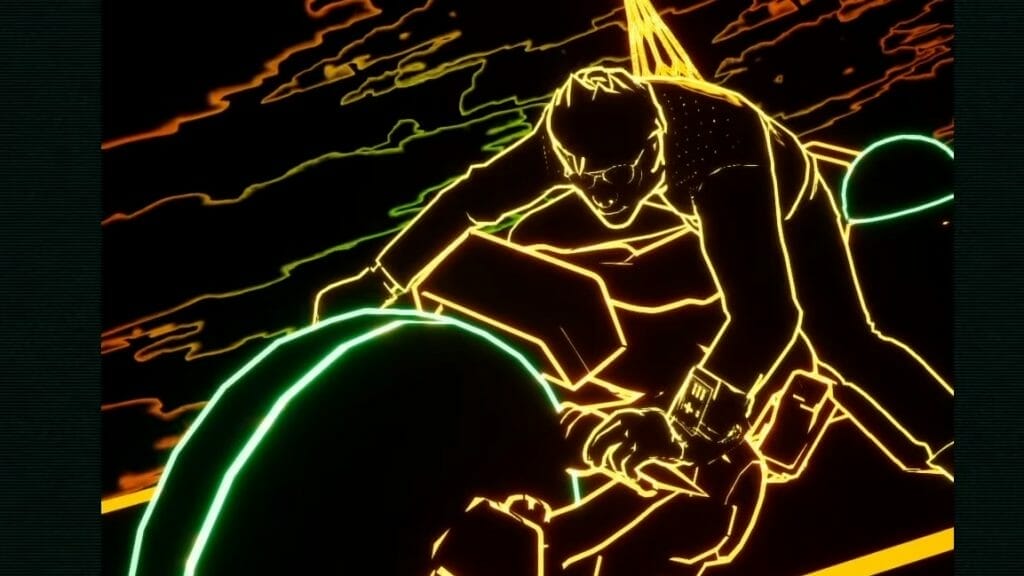

Travis Strikes Again is a 2019 action game, which was written almost entirely by Goichi Suda. It’s an autobiographical game told in layers of metaphor about his life and his time within the game industry that uses Travis Touchdown, the protagonist of the No More Heroes series, partly as an insert for himself. Sandwiched between a homage to his Human Entertainment days and a return to the messy world of Shadows of the Damned (which, again, he made with Mikami’s help) is a chapter about an aging racing star named Smoking King.

It’s a story beat that feels exciting and triumphant, as players speed through a vector-graphics world while a galaxy of fans watches. The experience reaches its climax in a tense race against legendary racer Smoking King. It feels like a dream come true – only for the entire experience to come to a grinding halt, as Smoking King decides to settle things like every other boss to this point did: with a battle to the death. He realizes his glory days are behind him, and admits he’s too old to continue on. Still, Travis still tries to encourage him to keep going.

One could read this chapter as Suda revisiting the highs of the time he got to make a game for Capcom, one of the biggest studios in the world, with one of the most famous designers in all of Japan. If Travis is Suda’s stand-in, then the tired and aging Smoking King is Shinji Mikami, weary after being on top of the world for so long, his age catching up with him. Through it all, though, Suda still believes in him. Suda still wants him to make games.

We’re currently living in an age where the many abuses of the game industry are just now starting to come out, from the horrifying stories spilling out about Ubisoft’s management, to the normalization of crunch as a key part of the development timeline. These horrific events make people like Shinji Mikami stick out all the more. He truly believed in the medium as an art form, and encouraged those who shared that passion to deliver their very best. Shinji Mikami valued people and creative visions, and every decision he made in his career since he directed Resident Evil really shows this.

Shinji Mikami changed the lives of many people, giving them a chance that this brutal industry would never do under normal circumstances. While he’ll always be remembered as the father of survival horror, with a few loud GOD HAND and Vanquish fans in the background, his real legacy will be the people in this industry he encouraged to continue creating. The world of gaming would have been a wildly different place if he wasn’t there, less for the games he helped make, and more for those he helped support – and that’s just the people we publicly know about.