Studio Ghibli was established in 1985, following the success of Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, which opened the previous year In the years that followed, the studio would go on to release twenty films, , with an upcoming feature based on Yoshino Genzaburo’s 1937 novel How Do You Live? currently in production. One of the studio’s most famous films, though, is Spirited Away. The 2001 film was a critical darling, and became the first recipient of the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature (a category introduced in the 2002 ceremony), and has since gone on to become the highest-grossing film in the history of Japanese cinema

The work focuses on the young girl Chihiro Ogino as she works for the malevolent ruler of a bathhouse situated in an abandoned amusement park. The choice of an amusement park as the film’s setting reflects the recession that struck Japan in the 1990s, which saw several theme parks, like the historic Nara Dreamland which closed permanently in 2006, suddenly defunct. The park depicted in the film helps establish an ethereal quality, and provides a suitable location for spirits and kami to reside and work.

Numerous beings exist within the grounds’ confines, including a large radish spirit bearing a sake-cup hat and traditional sumo attire. This particular character is known as Oshira-sama in Japanese, which refers to a similarly-named agriculture kami also known as Oshirabotoke. Said namesake can be found mentioned within the northeastern sections of Japan, where they serve as a tutelary deity which presidesover both agriculture and silkworms. Houses in northeastern Japan often contain a kamidama or alcove that enshrines Oshiro-sama. Moreover, a festival day honoring the kami exists in the lunar calendar, and people provide offerings to the deity and move dolls in a dance-like motion to ensure protection from Oshiro-sama.

One of the most recognizable characters in Spirited Away is No-Face, known as Kaonashi (which translates to “Faceless”) in the original Japanese script. He initially appears as a spectral, shadow-like entity but, through the absorption of others, he obtains their personalities and begins displaying greed and avarice. He ultimately abandons those traits when Chihiro refuses his offer of gold, and instead accompanies the girl on her journey on the train to meet Zeniba, the benevolent older sister of Yubaba. While not based on any specific yōkai, No-Face does take inspiration from the silkworm. The production of silk in Japan goes back centuries, and originated in China approximately 5,000 years ago.

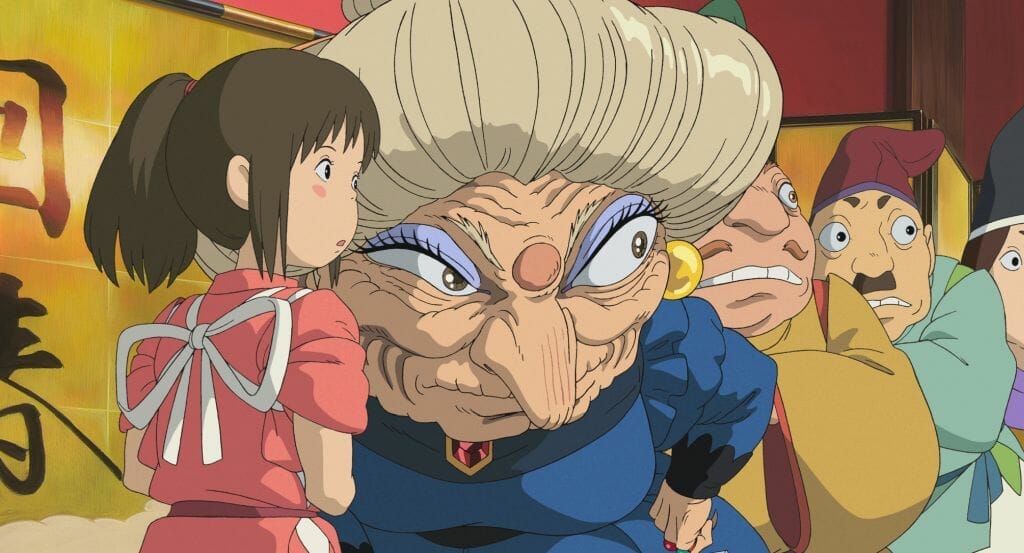

No-Face’s behavior, meanwhile, as a rapacious, greedy creature who motivates several of the bathhouse staff to do his bidding, reflects the general atmosphere of the bathhouse itself. Proprietress Yubaba exhibits cruel and avaricious traits as the onsen’s owner, surveying her domain with an iron fist, and going as far as to steal Chihiro’s name and forcing the girl into a life of indetured servitude. She is based specifically on the yama-uba, the “mountain crone” of folklore. Various different depictions of the crone exist, with the classic image of her being a decrepit hag that may be cannibalistic. This image from folklore forebears helps make for a great antagonist, with Yubaba as a modern variation of the yōkai. She perceives fortune as her primary motivation, mistreating her employees (and anyone who might wander into her realm, as seen with Chihiro) in order to obtain gold.

On the flip side, her older sister Zeniba exhibits the opposite characteristics: although initially intimidating in her first appearance, she is willing to assist Chihiro in recovering her name, as well as that of the amnesiac Haku.

Haku happens to be a river spirit, his real name being Nigihayami Kohakunushi. Though he first meets and befriends Chihiro when the latter arrives at the onsen, their history extends further back than the girl could ever begin to fathom. Moreover, Haku is able to take the form of a white dragon at will, which allows him to fly. Dragons in Japanese culture have a deep folkloric history, with numerous examples including the eight-headed and eight-tailed Yamata no Orochi (defeated by the kami Susano’o) and the Azure Dragon, which is one of the Four Symbols representing such concepts as the east and spring.

In addition to the examples noted, Spirited Away makes numerous references to other mythology and folklore throughout its run. This includes the three rolling heads known as Kashira, a reference to the traditional red-and-white Daruma dolls regarded as symbols of good fortune in Japan. Kamaji, the being running the onsen’s boiler room, is based upon the tsuchigumo: a spider-like yōkai appearing in the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki that aggravate Japan.

Even some ushioni appear as minor characters inhabiting the onsen. They are explicitly based on the similar yōkai, also known as gyūki, who most frequently appear in places such as beaches, forests and ponds. Various ushioni stories exist with varying details, but the most common one depicts them as having cow heads and spider bodies. According to folklore accounts, they can produce poison, and typically use it to attack any nearby humans. Various namahage also appear in the film, also as background characters who patronize the bathhouse. Their folklore forebears are humanoid yōkai that resemble oni, and New Year’s rituals in Japan occasionally involve participants dressed as them visiting houses to reprimand any misbehaving children.

Such examples show how Spirited Away draws extensively from Japanese folklore and history to inform its story. The characters all dress in traditional kimonos and court attire, resembling Heian-era forebears, which contrasts with the more modern imagery of the amusement park that serves as the onsen’s home. The park itself, meanwhile, is reminiscent of such liminal spaces that one might encounter in classic folklore.

Throughout Japanese fiction and mythology, humans encounter yōkai in various areas such as temples, their own homes and similar spots. In this light, the abandoned park functions in a comparable vein. Spirited Away presents modern life as still being highly connected to the supernatural and extraordinary – even though modern conveniences such as parks and motor vehicles exist in our society, they inhabit the same space as the yōkai and spirits of folklore ,who have never really disappeared. With this in mind, Chihiro’s experiences at the onsen reveal how yōkai can still be found, wherever one might go. Like GeGeGe no Kitaro and Mushishi, Spirited Away looks inward towards a supernatural past to show how the unusual can still be experienced by humans.