Content Warning: Contains frank discussions of Aoi House’s problematic elements, which include homophobia, female objectification, and queer fetishism. Reader discretion is advised.

To say the early 2000s was a wild frontier for anime fandom is an understatement. Television blocks like Toonami introduced young audiences to a multitude of series that they’d otherwise never experience in their lives. The internet was, for the first time in human history, commonly accessible to a majority of North American households. Forums, either sprawling or niche, could link unrelated people together for the first time in history. This was an era where fans not only realized they were not alone, but they could also create material celebrating this newly united western anime fandom.

It is in this context that Aoi House was created. Distributed by Seven Seas Entertainment and proudly heralded on the omnibus’s back cover as “IGN.com’s Third Best Manga of the Year,” Aoi House is an American comic that lovingly pays tribute to every manga, anime, and geek culture reference that seemed to saturate the years in which it was first published.

For many, it was like a sweet sundae — a desert offering fans excess of everything they wanted and more. Much like a sundae, though, if fifteen years pass, it’s almost certain that the ice cream’s long since melted and the goop leftover has gone rancid. Aoi House is a wonderful snapshot of an era of anime fandom, but it’s a snapshot that illuminates many of the problems that pervaded early anime fandom in America. While it offers a loving tribute to many nostalgic anime of the ’80s, ’90s, and early 2000s, it’s also a comic centered on fairly sexist wish-fulfillment that’s more than a little homophobic.

The Story

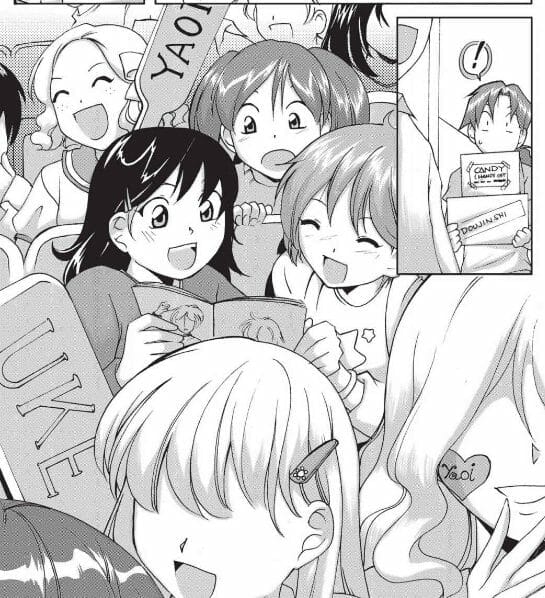

Aoi House revolves around two guys, Alex and Sandy, who happen to join an on-campus house at their college. It’s sort of a co-ed fraternity. The club members are all enthusiastic yaoi fangirls who, at first, think Alex and Sandy are gay and into yaoi.

Upon realizing they’re straight, though, the club members… well, they decide to force them to watch yaoi, coerce them to act gay around one another, and ensue in actions that would be kindly referred to as “criminal sexual harassment” if this story were based in any realm of realism or logic.

The plot itself can safely be divided into three arcs: an introduction, in which the characters get used to campus life and their club-mates; a convention arc that takes up the end of the first omnibus and first half of the second; and the finale, which goes so far off the rails that it merits its own discussion separate from everything else.

If Aoi House were to be categorized into a genre, it would fit securely in the “harem” genre of romantic-comedy, popularized in mainstream fandom by Tenchi Muyo! and Love Hina. As such, the characters all occupy very rigid and precise archetypes. Elle, the Aoi House club president, is an ice queen tsundere. Nina, the vice-president, is the aloof badass. Jessica, a nurse-in-training, is essentially the token fanservice character, Morgan is the wild genki girl, and Maria is the curvy shy dork.

If these sound like characters you’ve seen a million times before, that’s because they are. The characters in Aoi House, for the most part, aren’t developed far beyond their tropes. Elle seems to be the big exception to this rule, though her development primarily focuses on the core conflict of each arc, and rarely affects the other core players.

While it is no shock that the shy dork Sandy ends up with equally shy dork Maria, Alex’s romantic situation proves to be far less logical. At the outset, it appears he will wind up with Ellie. Halfway through, though, it becomes apparent that Morgan also holds strong feelings for him. This feels shocking to the reader, since up until this point there has been no indication that Alex has feelings for Morgan. Yes, we see hints that Morgan has a crush, but the story spends more time centering Ellie’s complicated feelings about her new roommates, juggling her disapproval of them with her growing attraction to Alex. All this is basically relegated to the margins of the plot during the anime con arc and after. While the title’s first half sets up the romance quite well, the second half strangely enough drops the ball, allowing character arcs to stall and stagnate until the end.

A Love Letter to Fan Culture

That said, the primary appeal of Aoi House — arguably, the core reason it exists — is to serve as a love letter to anime fandom as it existed in the 2000s. There are several chapters devoted to characters dressing in cosplay and reenacting scenes from classic games and anime. A whole two chapters are devoted to the characters recreating scenes from Utena, Final Fantasy VI, VII, VIII, and X (showing blatant disrespect in the process to the superb Final Fantasy IX).

There are references to anime and games in every scene, to the point where listing them all would be an exercise in futility. Evangelion, Ah! My Goddess, Sailor Moon, Fushigi Yugi — basically, any anime that had a fanbase before 2010 plays some role in this series. Numerous non-anime/gaming references even find their way to center stage, including a girl named Stephanie Kane and her bat pet Babs, as well as two girls named Harley and Ivy, all clear references to the Batman mythos.

The series’ middle arc, the convention arc, is an entire love-letter to Katsucon. The characters go to Hatsucon: a convention that takes place over the course of New Year’s Eve into New Years Day. And though the convention arc is an over-the-top love letter to cons in general, it’s hard not to draw comparisons between it and Katsu, with them taking place around the same time of year and having a similar name.

Aoi House is a great example of a narrative that exists to support fan references, rather than a narrative that has references to lend to support it. For example, there’s a mall arc that features a Dance-Dance Revolution battle scene. Furthermore, the series is brimming with harem clichés and, when it isn’t throwing fan references at readers, the comic’s throwing sex comedy clichés at them. There’s even a multi-part panty raid arc, in which a little hamster runs around peeping at girl’s panties.

It’s difficult not to draw comparisons between Aoi House and Bryan Lee O’Malley’s Scott Pilgrim, since both were created around the same time. Both featured countless references to pop culture, but while Scott Pilgrim created a narrative with characters and arcs that stand out apart from the references, Aoi House prioritized celebrating geek culture over everything else. As a result, it’s more of a time capsule for the anime subculture at the but fails to rise far beyond that.

At the same time, it also is a time capsule for the more problematic elements that pervaded fandom.

Fetishization

Your enjoyment of Aoi House is dependent on how much you can distance yourself or compartmentalize the problematic elements scattered throughout.

The casual sexism is arguably the easiest to digest. The comic was written by male readers, and, thankfully, all the characters are of age. The sex comedy is milder than the titles it took inspiration from, like Love Hina, making it, while not excusable, at least an expected trope. For example, when the characters Sandy and Maria play Dance Dance Revolution, it is not at all surprising when Maria’s jiggling breasts distract Sandy, resulting in a clueless Maria winning while Sandy ogles her.

What is more uncomfortable is the blatant homophobia, and the way gayness is often portrayed as something to be fetishized by women or something to be feared by heterosexual men.

The series focuses primarily on yaoi fangirls, a subset of fans commonly referred to as “fujoshi,” nowadays. Many longtime fans probably remember the stereotypical yaoi fangirl as a young teen who ogled and fetishized the romantic and sexual exploits of queer men because they thought it was “hot.” More still likely will relay tales of paddle-wielding fangirls being a convention blight during the period.

Similarly, Aoi House really fetishizes queerness in profoundly uncomfortable ways.

As alluded to earlier, the Aoi Club, itself, fetishizes its male members, subjecting them to humiliating and fairly abusive exploitation. The club often pushes Alex and Sandy into scenarios where they will be put in sexually suggestive positions for their own amusement.

For example, they are pressured into going to the bathroom or showering together and forced to watch explicit yaoi in a Clockwork Orange-esque set-up with their eyelids peeled open. Most galling of all, though, for the longest time, the character Morgan even refers to the boys as the club’s “yaoi pets,” indicating that they see the boys more as playthings to enact their craven fantasies upon.

This culminates in a yaoi panel at Hatsucon, during which the character Elle forces Alex and Sandy to cosplay various ships (including Shinji and Kaworu in Evangelion and even Harry and Draco from Harry Potter), while giving a speech about how amazing yaoi is. Rather, she discusses how hot it is to see two men bang regardless of whatever emotional connection they may have, even going as far as to celebrate Mario and Luigi Rule 34.

It’s a tongue-in-cheek scene, for sure, but this fetishization of queer identity for the sake of pornography is also reflective of yaoi fandom at the time. It is telling that even Maria, a more chaste character who’s uncomfortable with watching hardcore porn, only talks about male-male relationships in terms of physical intimacy rather than emotional intimacy.

This makes it even more uncomfortable whenever actual gay characters are presented.

Early on, we’re introduced to Carlos, a queer character who founded the Aoi House. Carlos is either a gay man who is also a drag queen or a trans woman, but the story never really explains enough for us to understand as an audience either way. Carlos is treated as a punchline in every scene he’s in, being just a stereotypical queer man who, much like the famous cosplayer Man-Faye — who makes a cameo alongside the Pedobear and a woman named “Monica” (possibly voice actor Monica Rial?) — exists solely as a stereotype rather than an actual person.

Most uncomfortable of all is a scene, where Alex is forced to go on a date with Carlos. In it, every interaction between Alex and Carlos comes across as Alex fearing the gay character might molest him. It’s profoundly uncomfortable.

Queer women, though? Entirely different story.

Later on, the characters are introduced at Hatsucon to the rival Uri House, who, rather than celebrate yaoi, celebrate yuri. These characters are fairly level-headed, with both male and female characters who get along fairly well. The women are either bisexual or lesbians, but are treated with some degree of dignity, minus one scene where the two girls fondle one another. It’s also telling that Nina, the only member of Aoi House to never be a target of romance for Sandy or Alex, finds herself in one gag scene having a threesome with two women from Uri House, indicating that Nina might be bisexual.

In some ways, this blatant bias is just another component of the 2000s anime fandom time capsule, as it demonstrates how neglected queer male fans within the anime fandom were at that time. This begs the question, though: should we judge Aoi House from our modern lens, when the series exists as a reflection of what fandom looked like at that time? This question is one without an answer, since it really depends on what you as an audience member feels when returning to this comic.

Let’s Talk About That Final Arc

As mentioned before, Aoi House’s plot can be divided into three core arcs. Most of the emotional narrative culminates with the conclusion of Hatsucon, but with a few dangling threads remaining, the series continues into an arc that feels completely detached from everything that existed before.

In it, the Aoi Club lands in Silent Hill, where they’re confronted by a whole bunch of supernatural entities. As a result, Elle joins forces with the rival Uri Club to go rescue them. The group does battle with the Necronomicon from Evil Dead, Cthulhu, and tons of Shadows, along with a Cow Head entity that could either be a reference to the Japanese urban legend of Gozu or the Takashi Miike film of the same name.

While the fantasy action is beyond belief, the revelation about Aoi House’s true nature proves to be more bewildering. Namely, everything the club does is being filmed and broadcast over the internet without Sandy or Alex knowing about it.

Throughout the series, it’s revealed that a mysterious figure known only as “Oniisan” is observing and interviewing the girls of Aoi House without the main characters really knowing who he is. It turns out that Onissan is actually Elle’s elder brother who, as part of a get-rich-quick scheme, decided to create a reality TV show on YouTube that showcases the day-to-day life of a college yaoi club.

There’s something inherently unsettling about the idea of the main characters being exploited by this mysterious Big Brother figure. While Aoi House did predict the ever-increasing demand for live entertainment online, it also feels incredibly demeaning and borderline pornographic, upon reflection of the fact that the other girls in the club know the boys are being filmed and choose to humiliate them anyway. It makes the entire cast far less likable, especially after the revelation that the series’ most humiliating moments were orchestrated by Oniisan.

The Strange Melancholy of Nostalgia

Aoi House’s final chapter sums up the next year or two of the characters’ lives in a rushed, super-fast sprint to the end, with a brief epilogue that offers a series of wish-fulfillment “Where Are They Now” segments. Some are logical, like characters getting married, having kids, or getting dream jobs. Others skew far siller, with goals like winning American Idol for singing “Eyes on Me” from Final Fantasy VIII, or a hamster getting a pig pregnant.

You don’t walk away from Aoi House feeling a sense of emotional catharsis. Instead, you walk away with a sense of possibly painful nostalgia. It’s a reminder of a ton of strong memories of the anime fandom that existed in the mid-2000s. At the same time, it ends with a feeling like nothing you just read actually mattered, since it’s so clearly wish-fulfillment that ultimately reminds you of how much has changed in the greater fan culture since it was written.

In so many ways, the subculture has improved since those days, especially in regards to the acceptance of queer people in fan spaces. Regardless, it’s hard not to feel melancholic to see all these stories lovingly referenced in this comic. Titles that, nowadays, often go overlooked. It is genuinely sad to see the character Elle cosplay Rosette from Chrono Crusade, a character notorious for her heartbreaking end in the anime’s last episode, only to realize that a modern reader would read this and just not get the reference.

Is Aoi House worth reading in 2020? I would argue that it is, if only to remember an earlier time in the anime fandom. Is it a great read, though? Well, it is a great tribute to anime of that time. Upon finishing it, though, I felt an urge to go through my closet and fish out old copies of Ah! My Goddess, Evangelion, and, yes, even Love Hina, to feel a strange sense of melancholy for the days when I first discovered them at my local library.