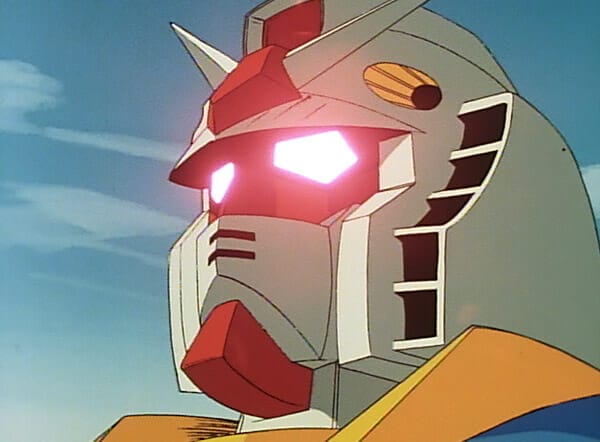

In this day and age, countless examples of mecha and robots can be found within Japanese popular fiction. From the Mobile Suits in the Gundam franchise to the titular humanoid units of Mazinger Z and Getter Robo, mecha have a great history within Japanese media. Most fans of pilotable robots recognize the most popular and influential names in mecha, but when, exactly, did the genre originate? How far back in history can we, as anime fans, trace the robot in Japanese pop culture?

As it turns out, the archetype traces its roots to World War II, if not earlier. Some of the earliest examples of the mecha can be found in propaganda, which was produced to symbolize Japan’s military might as the country fought against (and ultimately lost to) Allied forces, especially the United States. This article will examine the development of mecha in Japanese fiction from its earliest examples, beginning with its war-period predecessors and advancing to the 1960s. It serves as the first of a series dedicated to the giant robot, exploring the history of the archetype in Japanese popular media to the present day.

To begin, I shall make a clarification: the term “mecha” as used in this article applies specifically to pilotable (or, in one case, remote controlled) robots popularized in such manga and anime as Gundam and Mazinger Z. As such, other examples of robotic constructs or cybernetic beings, like Astro Boy or One Piece’s Franky, will not be considered in the definition. That said, they may be considered in the historical development of robot fiction in Japan. Regardless, this article series will primarily focus on the mecha as defined above.

As stated in the introduction, the concept of mecha initially developed during World War II, as part of the propaganda machine designed to present Japan and its military as a sort of supreme colonial force in both Asia and the world. Japan’s expansionist behavior during the war led to the country’s brief dominance of the Pacific into the 1940s, and the government subsumed its media into the propaganda effort. Many manga and anime produced during this period emphasized the country’s military aggression as it entered the war on the side of the Axis powers. For example, the popular dog character Norakuro enlisted as a soldier, becoming a potent symbol of Japan’s push towards a cultural and economic dominance of Asia, and tales of Japanese soldiers fighting the good fight proliferated.

The earliest known mecha production, a manga, debuted in 1940 – known as Denki Dako (which can be translated to “Electric Octopus”), this work focused on the exploits of a young boy who pilots an octopus-shaped mecha. Three years later, Kagaku Senshi New York ni Shutsugensu (“The Science Warrior Appears in New York”), an overtly propagandistic manga depicting a massive robot’s devastation of New York City, made its debut. As a bit of trivia, the creator of Kagaku Senshi, Ryūichi Yokoyama, would later direct Otogi Manga Calendar, the first televised anime in history, which ran from 1962 to 1964.

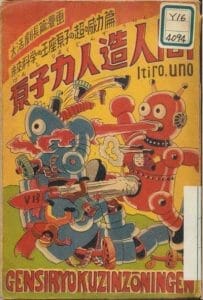

These two early examples illustrate how the mecha genre practically began as war propaganda, with the featured robots representing Japan’s military aggression. Despite this, the militaristic aspect of mecha history is brief, as Japan’s wartime devastation and eventual loss against the victorious Allies in 1945 would have a profound effect on its society. The immediate postwar period, through the 1950s, was marked by intense economic recovery as the Japanese recovered from the horrible losses inflicted upon them, One significant postwar mecha work, known as Genshiryoku Jinzoningen, appeared in 1948 and was created by Uno Kazumichi via a pseudonym. This particular work presents one of the earliest examples of the exploration of nuclear weapons in Japanese fiction. Subsequent works, such as the classic 1954 film Godzilla, would be equally explicit in their treatment of nuclear testing and its potential global impact.

These two early examples illustrate how the mecha genre practically began as war propaganda, with the featured robots representing Japan’s military aggression. Despite this, the militaristic aspect of mecha history is brief, as Japan’s wartime devastation and eventual loss against the victorious Allies in 1945 would have a profound effect on its society. The immediate postwar period, through the 1950s, was marked by intense economic recovery as the Japanese recovered from the horrible losses inflicted upon them, One significant postwar mecha work, known as Genshiryoku Jinzoningen, appeared in 1948 and was created by Uno Kazumichi via a pseudonym. This particular work presents one of the earliest examples of the exploration of nuclear weapons in Japanese fiction. Subsequent works, such as the classic 1954 film Godzilla, would be equally explicit in their treatment of nuclear testing and its potential global impact.

After the dissolution of the Occupation government in the 1950s, Japan had more freedom to explore its own recent history as it continued its economic recovery. By the 1960s, the country entered a period of great economic prosperity known as the “Golden Sixties,” and its pop culture grew as television became a prominent part of society. One of the key developments of the era was the production of the first televised anime. Otogi Manga Calendar became the first serialized broadcast when it began in 1962, but a year later, it was joined by two other major productions: Astro Boy and Tetsujin 28-go. The latter, which became known as Gigantor when NBC picked it up for American distribution, qualifies as the first televised mecha program in Japan. The titular robot could be controlled externally with a special remote, operated by the young protagonist Shotaro Kaneda, who was famed for his detective skills.

Tetsujin 28-go features an episodic format, wherein the villains are primarily opportunistic humans hoping to gain control of the mecha for their own nefarious purposes. Said antagonists do not last for more than three episodes, with new villains appearing frequently. The show also happens to be one of the first anime to include sponsorship as a means of alleviating production costs. In its case, the sponsor was Glico, the confectionary company famous for its Pocky, which included the mecha on its candy wrappers as a promotional effort. Sponsorship of televised anime began when executives such as Osamu Tezuka discovered that they required outside assistance to balance the costs of animation. They could only reduce the animation so much, and requested sponsors to promote the shows to help finance them. This practice can also be seen with Astro Boy, which received support from the Meiji Confectionary Company. Astro Boy itself is also thematically significant for its exploration of humanity, as the eponymous android interacts with a world still struggling with discrimination.

As the ‘60s progressed, other robot-themed productions appeared on Japanese television. Cyborg 009 and Eight Man include the first cyborgs in Japanese fiction, and the 1966 comedy series Robotan features the eponymous household servant robot who has the ability to wield special techniques such as the “Robotan Punch”. Such works helped cement the television as a profoundly important medium for animation in Japan, and established some of the first recurring robots and mecha in Japanese media. Tetsujin 28-go, in particular, demonstrated the viability of mecha as it achieved popularity, and its eponymous robot became an icon of Japanese pop culture both in its home country and internationally. The following decade would become far more significant with the mecha genre, though – two distinct subgenres (Super Robot and Real Robot) emerged in the 1970s as manga and anime expanded, and some of the most iconic mecha works debuted.