In my previous article on mecha history, I examined various figures and genre standards that were introduced in the 1970s. The decade proved significant, thanks to shows such as Mazinger Z and Mobile Suit Gundam pioneering and popularizing the Super Robot and Real Robot subgenres, respectively. The 1980s continued this trend, offering real evolutions to both formats, while also helping to establish a number of new standards, particularly the concept of the multi-stage transforming robot. Moreover, as both Super Robot and Real Robot works saw releases over the course of the decade, particularly on television, international interest in mecha as a whole grew in turn. It was an era marked by bold strides and controversial practices, which formed a tapestry of content that could (and would) never be replicated.

In Japan, mecha anime experienced continued popularity as the nation entered the 1980s. The genre built upon the successes found in the previous decade, which saw the debuts of iconic properties like Giant Gorg and the iconic Gundam franchise. With regards to Gundam, though the original TV series did not achieve success initially, it eventually found an audience through reruns, leading to three new productions in the 1980s. The first, Mobile Suit Zeta Gundam, introduced a new generation of pilots, including the now-famous Kamille Bidan. The series proved popular with women, who made up roughly 30% of the audience at the time of the show’s debut.

Zeta’s successor Mobile Suit Gundam ZZ, was released the following year. In the series, Neo Zeon rose as a force composed of former Zeon remnants, who set their base up in an asteroid base. Haman Karn, who was introduced in Zeta Gundam as a supporting villain, returns to become the show’s main antagonist as the leader of Neo Zeon.

Feature film Char’s Counterattack debuted in theaters in 1988 and would go on to become a beloved staple of the greater Gundam franchise. The movie, which is based on the novel Mobile Suit Gundam High-Streamer by Yoshiyuki Tomino, is set in the in-universe year of U.C. 0093. It concludes the story of Amuro Ray and Char Aznable, with the former leading the new Londo Bell task force against the latter, who plans to destroy the Earth with an asteroid. In the same year, Tomino would write Beltorchika’s Children, which tells an alternative version of the story. These three Gundam productions, in addition to the 1979 original, would form a bedrock from which the franchise’s popularity could grow.

Tomino would also produce a number of other mecha projects during the decade, including 1980’s Space Runaway Ideon and the 1982 series Combat Mecha Xabungle. Xabungle tells the story of an orphaned boy named Jiro Amon, who wishes to exact vengeance against the person who murdered his parents. Like Gundam ZZ, Xabungle adopts a generally lighthearted tone for its story..

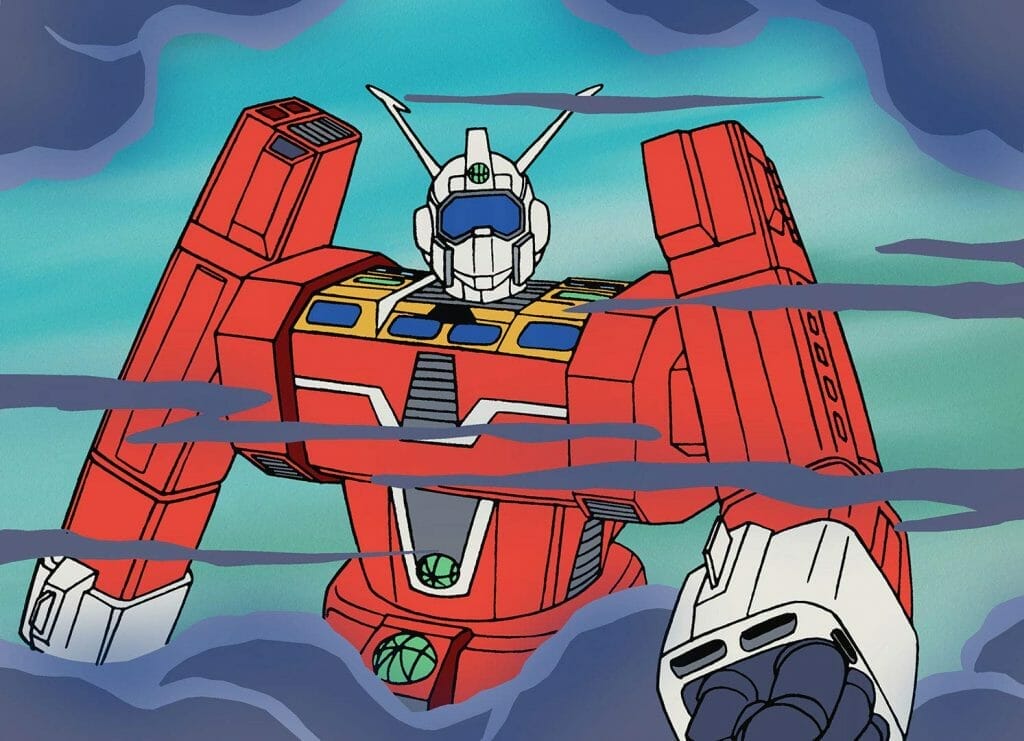

Ideon, by contrast, presents a more bleak worldview, focusing on a conflict between the villainous Buff Clan and the inhabitants of the planet Solo who are locked in a seemingly endless war. In execution, the title plays more towards the Super Robot subgenre. The eponymous Ideon is the combination of three separate units, each with its own pilot, which can attach to each other to form the iconic robot’s profile. It’s a concept that was quickly copied by other mecha works, with the most notable being 1981’s Beast King GoLion. GoLion was one of two shows that were, like the mighty robot itself, merged together to produce Voltron for American distribution (the other being Armored Fleet Dairugger XV).

This practice of combining shows to form a new production no longer exists, as it was essentially an artifact of 1980s syndication regulations. While no official law existed to govern which shows were allowed to be distributed in syndication, a rule of thumb suggested that a cartoon needed at least sixty-five episodes (ideally 100) to be syndicated on a daily basis, as the count ensured that a show could fill at least thirteen uninterrupted weeks of weekday broadcasts without repeats. . Since neither Dairugger XV nor GoLion had enough to pass that threshold, American company World Events Productions chose to merge the two together to satisfy the rule.

This practice can also be seen in another 1980s work, Robotech, which was produced by Harmony Gold. In Robotech’s case, three separate shows, rather than two, were combined to form a new narrative context that would see the works connected. In particular, the title brought together Super Dimension Fortress Macross, Genesis Climber MOSPEADA, and Super Dimension Cavalry Southern Cross, all of which were produced by Tatsunoko Entertainment.

Super Dimension Fortress would soon become the focal point of a legal battle that would affect the greater franchise for decades to come. Though this will be explained in a later installment, a 2005 court case ultimately found that Tatsunoko maintains ownership over the original footage and international licensing rights for the original Super Dimension Fortress Macross anime, though creators Big West and Studio Nue co-own the rights to the Macross characters and stories outside of Japan. The Robotech property, as an entity, is currently held jointly with Harmony Gold, and has been extended for the foreseeable future.

On the note of Macross, the franchise began with the release of Super Dimension Fortress Macross in 1982, which was created by Studio Nue and Big West, with mecha designs by Shoji Kawamori. Macross tells the tale of a great interplanetary conflict between the inhabitants of Earth and the Zentraedi alien race, with the eponymous space-faring battleship serving as the main space vessel for Earth’s forces. Though forebears such as Getter Robo explored the concept of transformable mecha in the past, Macross showed the units as individual mechs that did not connect physically in any way. The series presented this idea with the Valkyrie units operated by Earth’s pilots. Each unit had three different configurations, including a plane, humanoid mecha, and an intermediary step known as “Gerwalk” which had characteristics of both.

Another show used in Robotech, Genesis Climber MOSPEADA, was also produced by Tatsunoko and made its debut in 1983. The title follows humanity’s attempt to reclaim Earth from the Invid, an alien race who decimated and conquered the planet in the year 2050. Like Macross, MOSPEADA features transformable units in the form of the Legioss mecha, which were similar to Macross’ Valkyries in their construction. In addition, the show also includes powered armors known as MOSPEADA, which could transform into motorcycles.

Though shows like Macross and Zeta Gundam served as harbingers of the Real Robot subgenre, one would be remiss to ignore the thriving Super Robot category. Aside from the aforementioned GoLion and Ideon, shows like Giant Gorg, Chō Kōsoku Galvion, and Galactic Whirlwind Sasuraiger continued to find success over the course of the decade. Sasuraiger, in particular, is part of the influential J9 Series, alongside its predecessors Braiger and Baxingar. The series follows the story of I.C. Blues, a gambler who sets out to travel the solar system after betting a crime boss he can achieve that feat in a year. To do so, Blues enlists the help of three other people, as well as the eponymous transforming train mecha. Sasuraiger, specifically, bears the distinction of a musical score provided by Joe Hisaishi, who famously contributed scores to various Hayao Miyazaki films, including My Neighbor Totoro and Spirited Away.

Galvion, meanwhile, stars pilots who happen to be criminals, who agreed to operate the mecha in exchange for reduced sentences. The title features mecha designs by Koichi Ohata, who is best known for his work on iconic OVA Gunbuster. Galvion did not fare well critically, and it was subsequently canceled. Kokusai Eiga-sha, the studio responsible for the series, ultimately folded by mid-decade, and the toy manufacturer Takatoku went bankrupt before it was able to produce any merchandise intended for the series. In the years that followed, the series gained infamy as a rarity; a piece of lost media, kept alive only through TV broadcast recordings that continue to circulate to this day.

In addition to the growth of the Super Robot and Real Robot genres, the 1980s would usher in numerous spinoffs and related works, like the quirky SD Gundam and the genre-bending Gunbuster. Meanwhile, thanks to works like Voltron and Robotech, American interest in mecha saw remarkable growth, which would carry into the following decade. In the next installment, we will cast our gaze on works like these, as well as other mecha productions from the decade, particularly those that found their way to the world via the nascent direct-to-video OVA market.