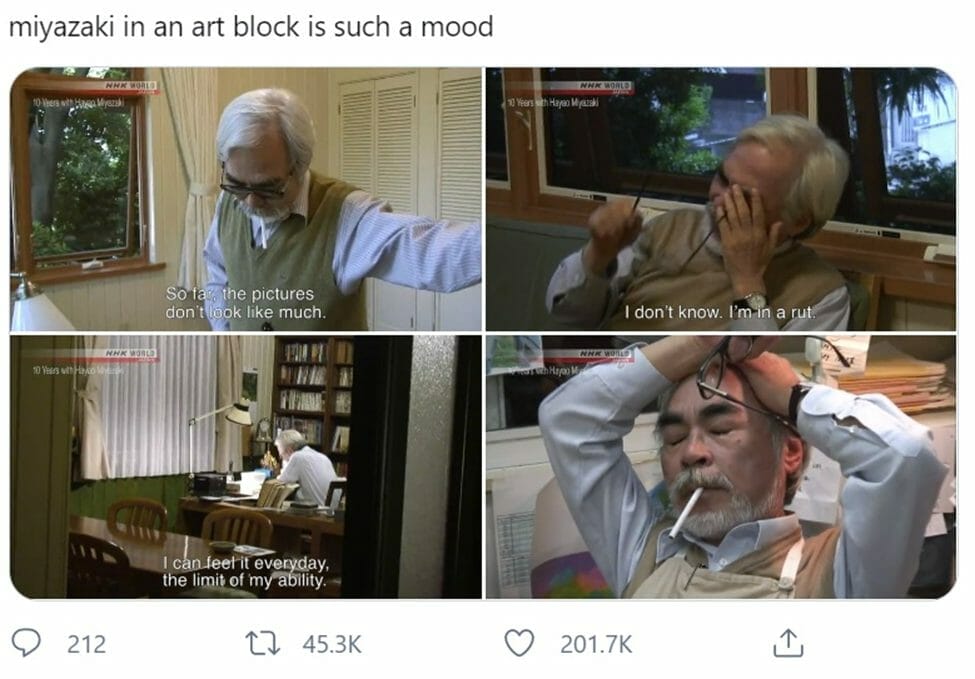

The myth of the animator-auteur has gained a lot of attention over the last few years. This is perhaps due to the rising popularity of re-watch podcasts that have centered the discourse around director-specific filmographies, a perfect fit for a weekly release schedule, or maybe even to Toshio Suzuki, the tireless behind-the-scenes operator at Studio Ghibli who has worked to position Hayao Miyazaki as a cultural institution. Seriously, Miyazaki memes have become a cottage industry on the Twittersphere as of late. But whatever the case may be, the idea of the “god-director” has really taken hold in the popular imagination.

But auteur theory has been around for a while. It can be traced to a group of cineastes in postwar France who wanted film to be taken more seriously as a medium of artistic expression. These critics argued that cinema wasn’t solely driven by commercial interests, pointing out that some directors exert the same control over a film that an author does over a novel. Suffice to say, this idea caught fire.

Auteurism soon became the gold standard in academia. Scholars began elevating directors to this vaunted position, combing through their work in order to pick out enduring themes and signature flourishes. This lens was predictably applied to the Japanese animation industry as it experienced its first boom in the 1980s, when a rising economy propelled a group of budding artists to international prominence. Susan Napier, who taught a course on the subject decades later, included four individuals in this first wave of “anime auteurs”: Katsuhiro Otomo, Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon, and Mamoru Oshii.

While not the oldest of the bunch, Mamoru Oshii’s star arguably ascended first. An ardent fan of European cinema, Oshii worked in an intellectual tradition and applied that energy to his early films. But it wasn’t until Patlabor: Early Days—and especially the subsequent two movies—that Oshii established himself as an artist with a clear vision: namely, to track the evolutionary changes technology forces upon humankind.

By the mid-’90s, Oshii’s reputation as a premier director was all but certain. Unsurprisingly, he cast a long shadow, so much so that when he wrapped up his involvement with Patlabor in 1993, the franchise—except for a handful of manga and light novels—was left fallow for nearly a decade. WXIII: Patlabor the Movie 3, a film beset by production issues, didn’t release until 2002. While it is by no means the strongest entry in the trilogy (if it were, this essay would have been written long ago), or even an unsung classic, it’s not without merit.

The final Patlabor movie exists on the fringes of the fandom, circling the drain of critical discourse. “Wasted XIII? More like wasted potential.” But the venom it has continued to engender remains unjustified—it’s a competent, albeit uneven, film. I believe its flaws are unfairly exacerbated due to Oshii’s noninvolvement and the suffocating influence of his reputation. Just because Patlabor the Movie 3 is devoid of an auteur figure, though, doesn’t mean it’s devoid of artistry.

“God in Film”

Seventy years ago, films were considered a “lesser” art form, occupying a similar position in popular culture that novels did in the early nineteenth century (and video games did until recently). Detractors argued that movie production shared more in common with the workflow of an assembly line. Studio executives commissioned new projects based on demographics and market demand, with a disregard for artistic expression. At least, that’s how it was largely perceived.

It wasn’t until the middle of the twentieth century that scholars began to seriously push back against these assumptions. A group of French theorists—most notably, André Bazin, François Truffaut, and Jean-Luc Godard—began noticing patterns in American films that spoke to a greater authorial voice. Even though Hollywood was producing a glut of westerns and noirs, the epitome of commercial shlock, they were able to identify patterns between movies that shared the same director. “What fascinated the French critics,” David Tregle points out, “was when an American director took a genre movie with a basic story and created compelling characters with an interesting story that amounted to more artistically than its parts would lead a viewer to believe” (6).

Truffaut made this argument in “A Certain Tendency in French Cinema,” an essay that many consider to be the founding document of auteur theory. In it he eviscerates the French film industry, criticizing the “Tradition of Quality,” an umbrella term he uses to refer to the entrenched popularity of novel-to-film adaptations. He takes issue with the mechanical and, quite honestly, rather pedestrian way in which most directors approach their literary source material. He contrasts this with a handful of “auteurs who often write their dialogue and…invent the stories they direct,” thereby creating something original and worthy of merit.

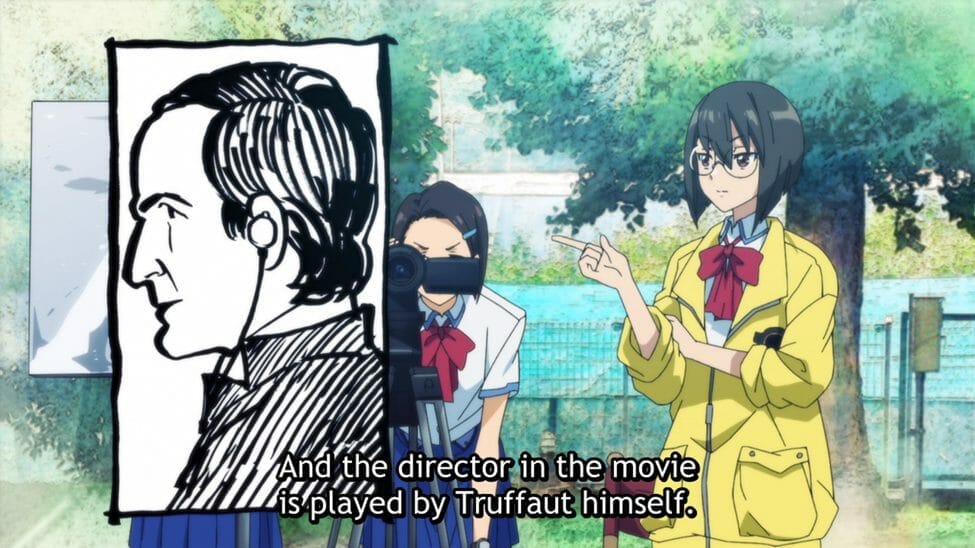

Coincidentally, Oshii is a fan of French New Wave, particularly the films Truffaut and Godard. Truffaut makes an appearance in episode 7 of Vlad Love, Oshii’s latest show.

Auteurism eventually migrated across the Atlantic, and when it did, it struck a chord. Andrew Sarris, an American film scholar, was perhaps its most public and passionate promoter. Even though he acknowledges that “auteur theory is…in constant flux,” he did establish some guiding principles. “If a director,” Sarris stressed, “has no technical competence, no elementary flair for the cinema,” they’re not an auteur (562). Furthermore, “a director must exhibit certain recurrent characteristics of style, which serve as his signature.” Otherwise, they’re not artistically advancing the medium.

These principles did not sit well with everyone. Some critics bristled at the exclusionary and male-centric vision provided by these theorists. In the pages of Film Quarterly, Pauline Kael resisted the growing popularity of auteur theory, practically going to war with Sarris. She wrote, “movies are so rarely great art that if we cannot appreciate great trash we have very little reason to be interested in them.” Unfortunately for Kael, Sarris won out in the end. By the ‘70s, auteur theory had become the de facto method of film criticism.

The pendulum has recently swung back, though. There’s been renewed interest to revisit these debates. Paul Sellors put forth a compelling case in “Collective Authorship in Film,” published in 2007. Sellors stated that “authorship of a film needs not identify only one individual,” emphasizing that “authoring can be a collective action.” And believe it or not, Patlabor the Movie 3 is uniquely equipped to address these issues given the legacy of the franchise and the film’s tumultuous production.

“Mutual Interaction”

Originally conceived as a one-off OVA set to release in 1995, development on Patlabor 3 stagnated for the better part of a decade. What began as a simple side story set between the first two movies soon morphed into a feature-length film that changed hands on numerous occasions. It’s a surprise the final version remains as coherent as it is, given that Triangle Staff, the studio originally tapped for animation, filed for bankruptcy during pre-production. Work eventually shifted to Madhouse, but not without acquiring a new co-director in the process. It goes without saying then that Patlabor the Movie 3 was not willed into existence by a single creative force. It took a village.

Even with these troubles, Fumihiko Takayama stayed the course and provided directorial oversight for the duration of the production. A veteran animator, Takayama doesn’t command the same respect as Mamoru Oshii, despite having a similar tenure in the industry. While still active at nearly sixty years old, Takayama’s resume is surprisingly sparse. He’s selective of the projects he takes on, preferring to work quietly and without fanfare. Still, he cultivates a distinct style that’s almost documentarian in execution.

Japanese fans have noted Takayama’s concern for visual verisimilitude. Instead of exclusively relying on flesh-and-blood characters to do his thematic lifting, he shifts meaning to “surrounding buildings, signboards, and interiors.” This concern for environmental detail can be found throughout his works, most notably in Gundam 0080: War in the Pocket. While part of a long-running franchise, with all the requisite glitz and glamour, 0080 still manages to be an exceptionally grounded piece that immerses viewers in the suburban complacency of a space colony.

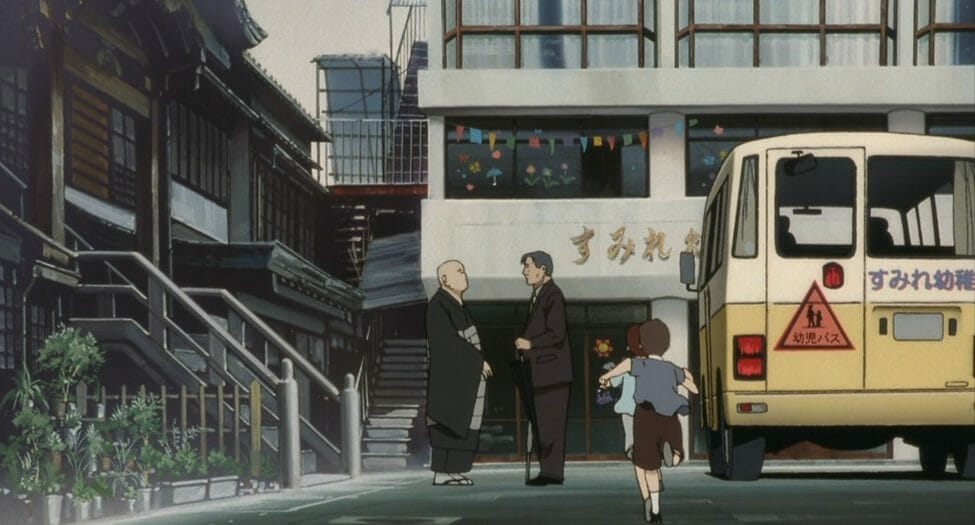

Similarly, Takayama elevates the setting of WXIII to the point where it becomes a central character. Unlike the Oshii films, which often take humans out of the equation to allow the audience to soak in the malaise of a post industrial wasteland, Takayama’s Tokyo teems with life. This diversity of personality is on full display during the montage sequences, which feature a pair of mismatched detectives sleuthing the backstreets of Tokyo to uncover the origins of a kaiju mystery. Whether they’re questioning a Shintō priest as a group of excited children run back to their school, or idly walking along the docks among a crowd of blue-collar fishermen, these scenes have an unmatched sense of place, which makes Patlabor 3 such a remarkably sensory experience.

This time capsule quality wasn’t unintentional. When it opened in theaters Takayama said that he wanted “to recreate how it feels to be living within modern-day Japan.” We get an intimate glimpse of a country that straddles two eras, a dichotomy made even more apparent by the protagonists’ age difference. Detective Kusumi struggles with computers and relies on Hata, his greenhorn counterpart, to navigate the digitized requirements of his job. Similar contradictions mark the film’s various settings, as the architecture of postwar Japan deteriorates and gives way to a more technologized present. Takayama foregrounds the background, and when it lands, it’s spellbinding.

The attention Patlabor 3 pays to its visuals also extends to its writing. Screenwriter Miki Tori stressed his commitment to realism when he later reflected on his creative process for the film. While not the most captivating or inspiring pair of gumshoes ever to grace cinema, there’s a core integrity to Kusumi and Hata that’s admirable. Tori exercises restraint with his characterization, avoiding the timeworn cliches that often plague anime. Kusumi, a fifty-plus year-old veteran, copes with the existential solitude of a bachelor existence. Hata, meanwhile, attempts to make a lasting and legitimate connection with a potential romantic partner, only for it to take a tragic turn. There are no easy answers. No one gets a storybook ending. There’s an honesty in their struggles that resonates on a human level.

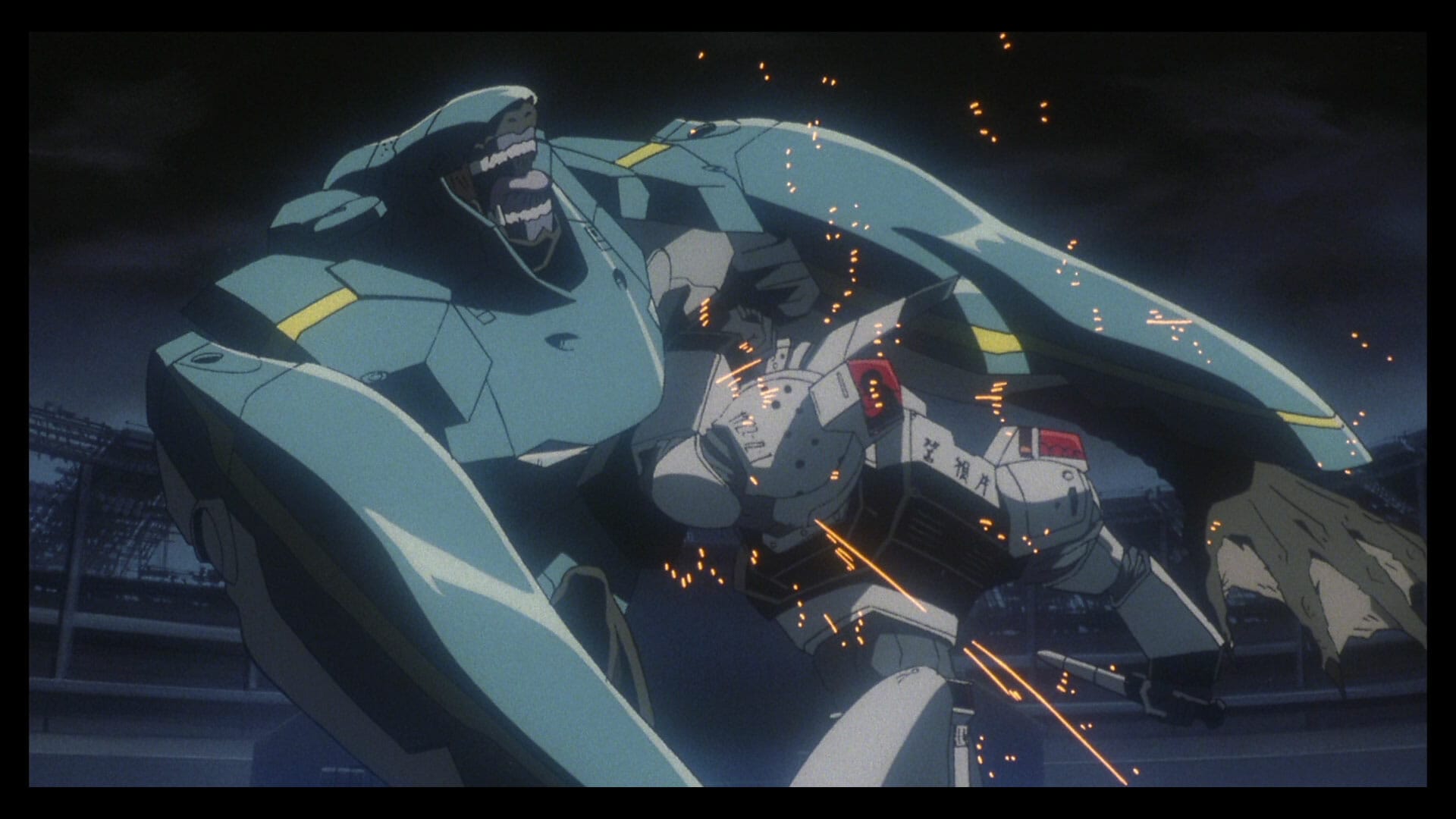

Furthermore, Tori doesn’t harbor any idealized notions about the corrupt and cutthroat world these characters must navigate. Unlike the Early Days, which adopts rather rose-tinted glasses when it comes to assessing power structures, WXIII can be quite sharp in its critique. The story of Patlabor 3 involves a Japanese biochemical company that’s developing organic weapons for the US military. In so doing, they subject unethical horrors upon a sentinel creature codenamed “Wasted XIII.” This being wreaks enormous havoc throughout Tokyo, polluting the neighboring bay and indiscriminately killing bystanders. Tori puts the blame for this destruction squarely on the shoulders of American imperialism and its pernicious presence in Japanese life. And unlike its predecessor, it doesn’t flirt with a nationalistic agenda, which makes for more consistent messaging overall.

In conversation with Mori’s writing, Kenji Kawai’s soundtrack does such elevating work. No stranger to the franchise, Kawai again provides a haunting score that compliments each scene so well. The music, while not the most memorable of the trilogy (“Unnatural City I&II” will forever be the tracks to beat), might be the most consistent. It’s equal parts ethereal and contemplative, which makes watching Patlabor 3 especially synesthetic. Stephen Holden, who reviewed the film for the New York Times, refers to this unique blend of music and atmosphere as “Technomood,” and for viewers of a more melancholic persuasion, it’s a real siren’s song.

To be fair, while these aspects sing in isolation, Patlabor 3 never really comes together in the end. The film arguably climaxes within the first forty-five minutes with the nocturnal chase through the Ark. Nothing in the second half matches the tension and dynamism of that hair-raising confrontation. The characters, while genuine, lack concrete arcs and are generally uninspiring. The mystery behind the bayside murders isn’t that captivating; parts of the movie absolutely trudge, submerged in the squalor that the animators so expertly capture. To compound these issues, the commentary on the military industrial complex and its desire for deadlier weapons, albeit consistent, remains skin-deep. It makes passing nods to a more nuanced examination but fails to provide a thorough evaluation that the subject requires. Which is unfortunate because WXIII has so much potential.

By writing this essay I do not mean to suggest that auteurism should be eliminated, or even that it’s worthless as a tool of critical analysis—that’s simply not true. Like Truffaut and Sarris (and probably even Oshii) have stressed, auteur theory exists as a useful paradigm to evaluate the artistry of cinema. Rather, I do believe the way in which critics have stressed the importance of an increasingly narrow selection of directors is an overcorrection. It’s no longer 1954. Film is a viable, celebrated, and yes, collaborative medium. By concerning our attention on such an exclusive coterie of artists, we do it a disservice. Some movies, like Patlabor 3, never transcend the sum of their parts. And that’s alright.

Works Cited

C. Paul Sellors. “Collective Authorship in Film.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art

Criticism, vol. 65, no. 3, 2007, pp. 263–271.

Holden, Stephen. “Machines, Noir Mood And Mayhem” New York Times, 10 January 2003,

<https://www.nytimes.com/2003/01/10/movies/film-review-machines-noir-mood-and-may

hem.html>

Sarris, A., 1962. Notes on The Auteur Theory in 1962. 1st ed. [ebook] New York. Available at:

<http://alexwinter.com/media/pdfs/andrew_sarris_notes_on_the-auteur_theory_in_1962.

pdf>

Tregde, David. “A Case Study on Film Authorship: Exploring the Theoretical and Practical Sides

in Film Production.” Elon Journal of Undergraduate Research in Communications 4.2

(2013) <http://www.inquiriesjournal.com/a?id=1700>

Truffaut, François. “A Certain Tendency of the French Cinema.” In Movies and Methods: An

Anthology, edited by Bill Nichols. Vol. 1. Berkeley, Calif., 1976.

Wikipedia. 2021. “Fumihiko Takayama.” Last modified Monday July 9, 2018.

WXIII: Patlabor the Movie 3. 2003. DVD. Directed by Fumihiko Takayama and Takuji Endo.

Geneon.