If you were to ask someone to describe a “typical” Studio Ghibli film, they would likely sketch out a vague hybrid of Spirited Away and My Neighbour Totoro. Depending on who you ask, they might also draw from some of the films that are slightly less popular, but still adored. Think Kiki’s Delivery Service or Princess Mononoke. It’s all but certain, though, that Hayao Miyazaki’s Porco Rosso, which was released in 1992, would hold far less sway. This is a shame, but it makes sense, given how different it is from the rest of the studio’s back catalogue. While the film doesn’t abandon the sense of character or mysticism that characterize other Ghibli releases, it combines the two in a completely unique way. What results is something almost unrecognizable.

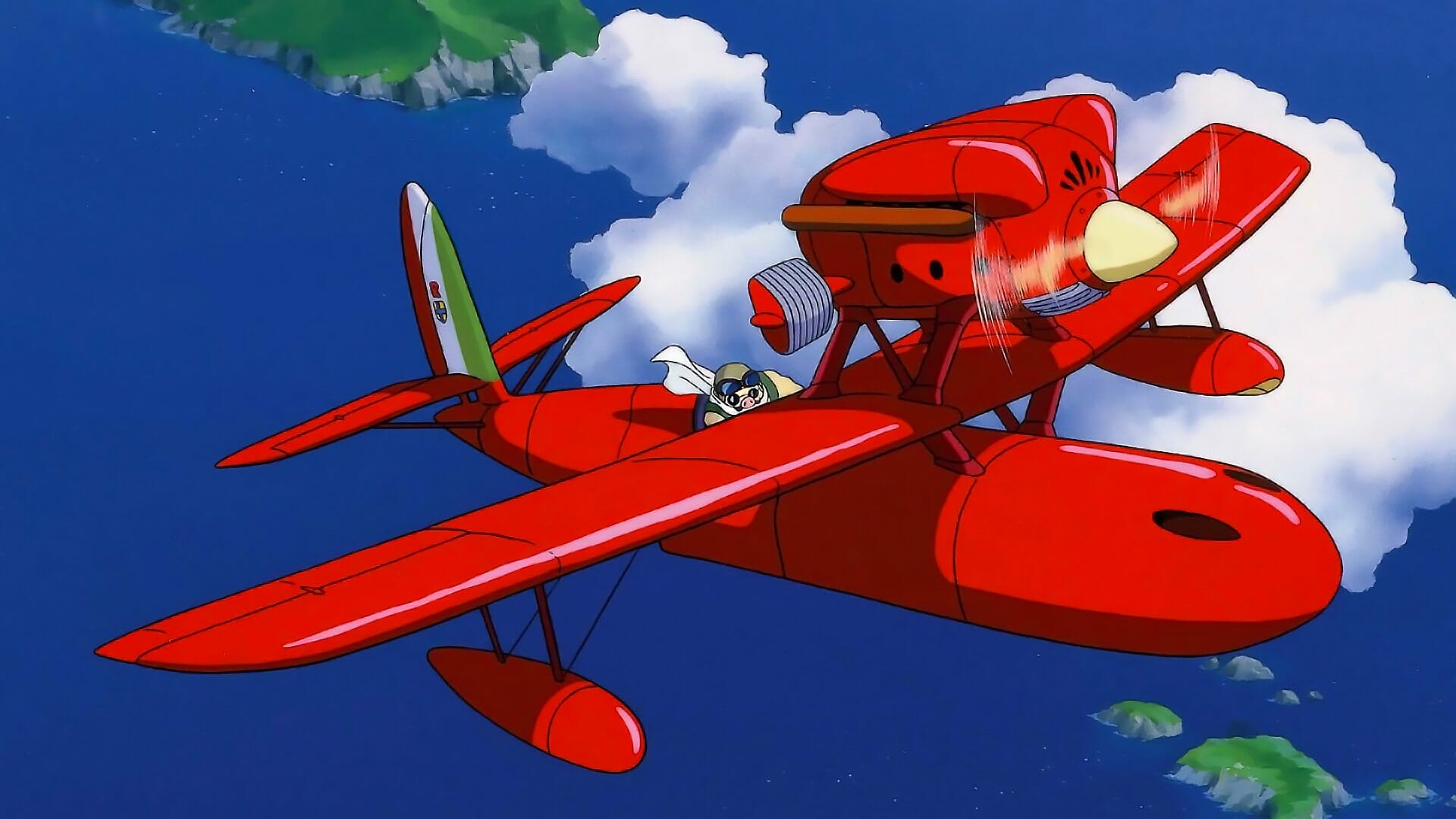

Porco Rosso concerns an eponymous World War I fighter pilot turned bounty hunter, eking out a living in 1930s Italy. The Great Depression is in full swing, and Porco has to contend with air pirates and the world not being like it was in the good old days. Oh, and he’s been cursed with the face of a pig.

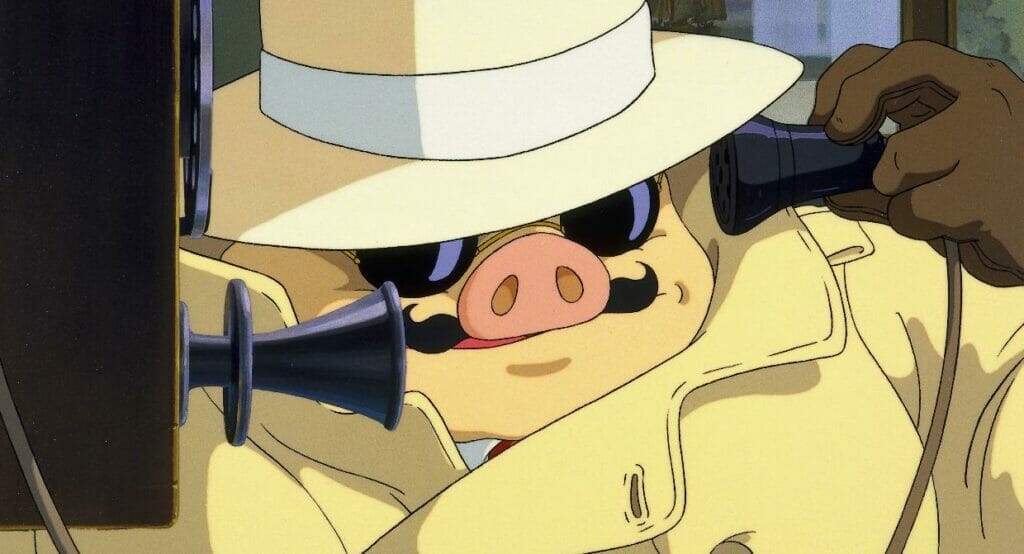

The most obvious way in which all this stands apart from other Ghibli films is in the things that have influenced it. Though set in the 1930s, Porco Rosso borrows most heavily from the cinema of the 1940s. Any viewers expecting to find another Spirited Away are left sorely disappointed when Porco gets tailed by the secret police, like in a gangster flick. The bar at Hotel Adriano, where pirates and pilots alike mingle, borrows heavily from Rick’s Café Américain in Casablanca. In a similarly romantic vein, its owner Gina is introduced to the audience by singing in front of a piano, moving her patrons to silence. In the next scene, she recalls her three dead husbands to Porco, explaining:

“I’ve got no tears left.”

As the score’s string section gives it its all, Porco replies:

“The good guys always get killed.”

So far, so feel-good. The film’s more somber undercurrent is compounded by another way in which it subverts expectations for a Studio Ghibli film: it gets political.

Though far from the studio’s only film to incorporate political themes, Porco Rosso wears them with unexampled prominence. Just as in real life, the Depression-era Italy portrayed in the film is in full grip of the National Fascist Party (PNF). Moreover, Porco isn’t happy about it. In perhaps the best line of the film, he reminds his friend Ferrarin, who flies for the Italian Air Force:

“Better a pig than a fascist.”

Here, the influence of the 1940s is even more obvious. Today, it’s rare to see fascists featured as the villains, even as their ideology drifts worryingly to the fore. During World War II, though, there was nothing more patriotic one could be than an anti-fascist, which bled through to the cinema of the time. Accordingly, Porco Rosso can be read as an earnestly anti-fascist text. Throughout the film, Porco’s free spirit stands in stark contrast to the totalitarianism with which the PNF seeks to break the country’s back.

Indeed, the main villain of the film could be fascism itself, given its urge to stamp out the individuality needed of bounty hunters like Porco. Rival pilot Curtis is certainly Porco’s nemesis, but he hardly has the makings of an antagonist. An over-the-top swashbuckling caricature, the only real weight he holds in the story is providing a reason for the final showdown. The film also doesn’t seem to take characters who present themselves as out-and-out villains too seriously. At the start, the pirate gang Mamma Aiuto kidnap a group of schoolgirls, one of whom asks:

“Are you bad guys?”

“Yep,” one of them replies gruffly before the schoolgirls proceed to run circles round them.

Porco’s main obstacle, then, is not a person or group, but an idea. Specifically, that of the past being replaced by a ruthless, fascistic present.

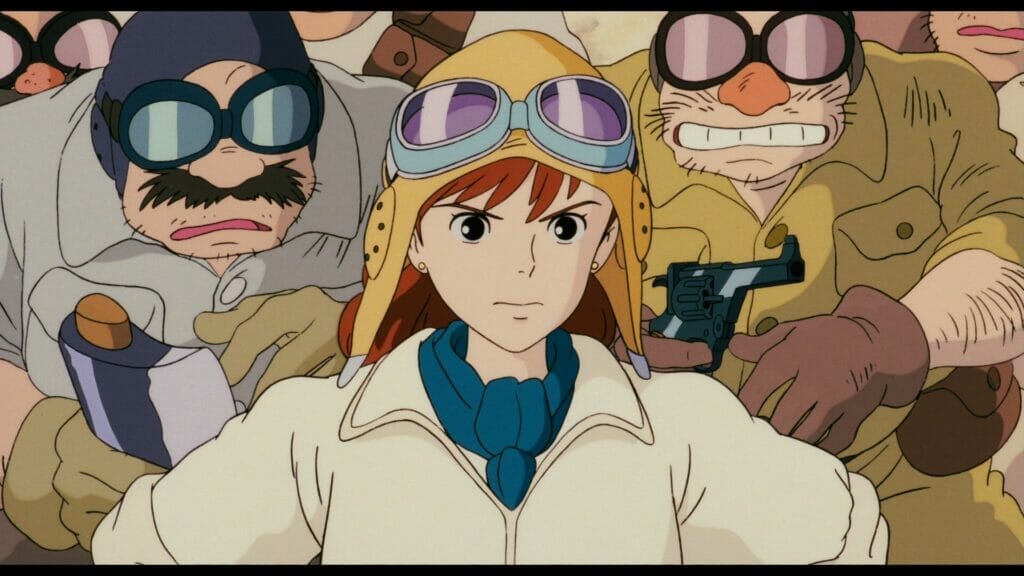

Of course, Porco is also flawed. Just as Porco suffers other people’s politics, so too do other people suffer his. In creating a world that is decidedly more adult, Porco Rosso veers frequently into sexism. Gina points out that the pilots who claim to admire her, all of whom are men, disregard her. When Porco first lays eyes on Fio, a brilliant engineer, he asks her grandfather Piccolo:

“Who’s the cutie?”

The moment becomes even more excruciating a few minutes later, when Fio is given the chance to introduce herself and explain she’s just 17. Porco tells her candidly that her age and her gender both make him reluctant to work with her.

The sexism doesn’t taper off, either. It comes to a head towards the film’s climax, when Curtis, a fully grown man, decides he is in love with Fio. This comes to a head when the mechanic is used as a betting chip in a wager between Porco and Curtis.. If Porco wins the dogfight with Curtis during the film’s finale, Curtis agrees to foot the bill for Porco’s new ship, which Fio designed. If Porco loses, though, Curtis wins Fio’s hand in marriage. The sight of Fio seated next to a literal sack of money is enough to make the viewer queasy. The Guardian seemed to concur in their 2020 ranking of 22 Studio Ghibli films, where it noted Porco’s sexism and put the film dead last.

That might be overdoing it. It’s clear that writer and director Hayao Miyazaki believes in Fio, even if his characters don’t. Her genius in engineering is obvious, and she’s far from helpless. By turns, she charms and shames an entire pirate horde out of trashing Porco’s new plane, earning their respect, and then some. Before the climactic dogfight, they scramble to shower her with flowers and take a picture with her. Far from looking down on her as a child – and one of the ‘wrong sex’ no less – as Porco does initially, they venerate her. Porco Rosso features sexism, certainly, but it doesn’t seem to agree with it.

It might be helpful to consider that the film offers two visions of modernity, in Ferrarin and Fio. Ferrarin has gotten with the times by embracing fascism. Fio, on the other hand, is on the decidedly better path, and works hard to have her talents recognized in what is still a man’s world. The stick-in-the-muds who are from the good old days and – more to the point – refuse to leave get some things right by staying in the past. Gina and Porco both mourn the days before fascism took over. Downstairs in the bar where Gina sings to obsessed regulars, though, it’s hard for her to become anything more than an object.

“I worry about you pilots, but you treat me like furniture,” she chastises Porco.

The film offers a view of times changing, and as far as it is concerned, sexism is on the way out. If misogyny isn’t outdated, as with Porco, it’s outright cartoonish, as with Curtis. Sometimes, though, it does feel more like a lazy shorthand – a cheap trick for telegraphing old-fashionedness – than more deliberate social critique. In breaking the Ghibli mold, Porco Rosso can miss as well as hit.

The film is not unalive to other cultural issues, though. During production, war broke out around where Porco Rosso takes place. Miyazaki has discussed how this complicated the process of making the film; indeed, the influence on its tone is obvious. In one scene, Porco recalls a dogfight in World War I, during which his entire squadron was shot down, except for him. As the music shifts to an ethereal dirge, Porco then describes the casualties – enemy and allied alike – floating back up from the clouds. They flew up, he explains, to join a band of thousands of other planes flying high in the sky, oblivious to his cries not to.

“I think God was telling me to fly alone forever,” he tells Fio.

It’s true that other Studio Ghibli films are capable of the same delicacy with their themes. Still, it’s rare that the themes are so inadvertently relevant – and therefore, harder to address sensitively – as with Porco Rosso.

It’s also important to note that, despite being packed with often grim subtext, the film is far from hopeless. It manages to be weighty, but not heavy. In large part, the key to pulling off this difficult balancing act is humor. Porco Rosso deals with death and disfigurement, yes, but it still finds time for pirates to bicker like the schoolchildren they kidnap. The theme for the Mamma Aiutos is so whimsical it robs them of any intimidation they try to muster. Even during the final showdown, Curtis and Porco abandon an epic, perfectly choreographed dogfight to start throwing things at each other. Moments like these help break up the more sober parts of the film, while also making them more cutting by contrast. As such, Porco Rosso is able to stay light on its feet while still leaving the viewer thinking.

That said, that’s only if the viewer wants to be left thinking. Like with the subtext, lots of little details and scraps of dialogue add substance to the story, but they aren’t forced down the audience’s throat. Porco remarks to Fio that he found his beloved plane in a warehouse. You could infer that Porco, too, is a relic, and a discarded one at that, but it isn’t essential to enjoying the story. In a flashback, we see that Gina named Hotel Adriano after an earlier one of Porco’s planes. In both cases, the moment is tender, but gone as soon as it arrives. Porco’s very disfigurement might symbolize how losing your friends in war can alienate you from human beings, including yourself. Then again, Porco seems to shrug it off so quickly, and entirely unpretentiously, that the viewer is tempted to as well.

Porco Rosso may not be the best-known Ghibli film, but it’s arguably the most rewatchable. Just when you think you’ve figured out every trick it has up its sleeve to subvert the studio’s tropes, you uncover three more. It’s as political as it is escapist. It offers up commentary just as easily as it provides levity. Put together, it comes at you kicking and screaming, like the planes the old pilots of the Adriatic are so desperate to fly.