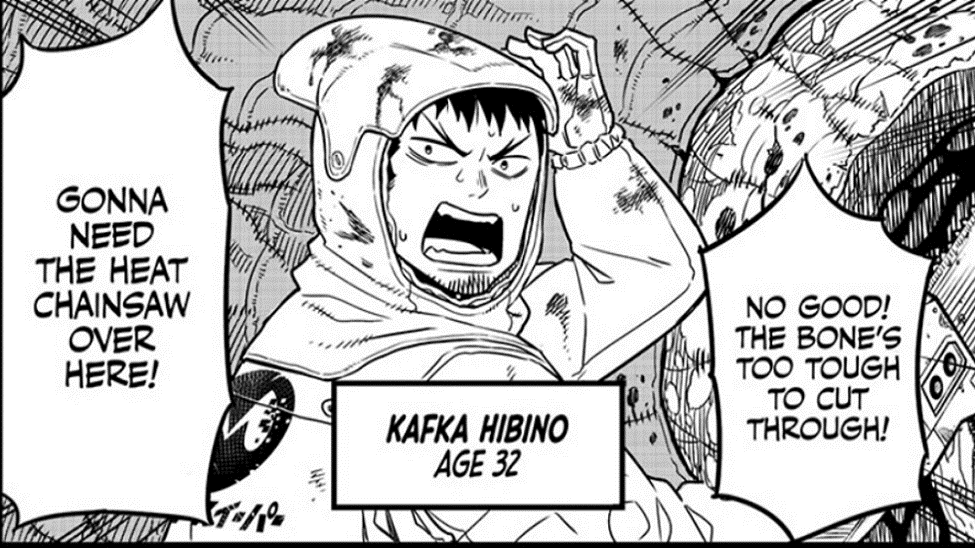

In the Tokyo of Kaiju No. 8, the destruction, chaos and gore left in the wake of giant monster attacks are an accepted part of daily life. Kaiju rampages are a regular occurrence, to the point that an entire economy has formed around anticipating, defending against and cleaning up. The series’ narrative draws readers into this world through a member of one such clean-up crew. Thirty-two year-old Kafka Hibino is a particularly stubborn cog in the cleaning machine, as he wages an “unsung war” against the never-ending mess of kaiju remains.

Hibino is hardly phased by the giant beasts (or their innards), despite the fact that he’s up close and personal with them on a daily basis. What does scare him, though, is the thought that becoming such a monster could ruin his life, dashing his idyllic fantasy of a future that could only be shaped by a lifetime toiling on the lowest rung of a dystopian system. It’s through this lens that Kaiju No. 8 asserts itself as a series about more than just Kaiju attacks; it’s also a manga about chasing your dreams, and the vulnerability of trying to do so after failing at it.

Fractured

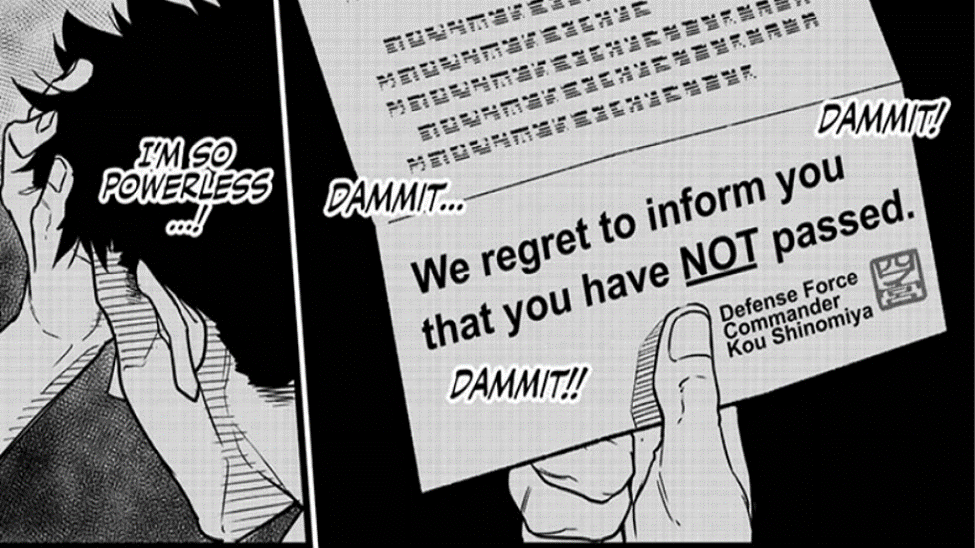

Unlike other shonen heroes, Hibino has clearly tried and failed to follow his dreams through his twenties. The noble ambitions of youth have already been beaten out of him, and he’s come to accept the rut that life has prepared for him. Rather than become one of the heroic few who fight the kaiju as part of the mythicised ‘defense force’, Kafka settled into a role at Monster Sweeper, working until age thirty-two: a year past the cutoff age for the force.

As fortune would have it, though, the Defense Force recently raised their application age limit by a year, and a daring on-the-job rescue rekindles Hibino’s motivation to apply. Minutes later, he swallows a strange insect, which triggers a transformation into a hulking, draconic beast. It’s this transformation that forms Kaiju No. 8’s thematic foundation, providing the keys to Hibino’s liberty through the cruel fate that burdens him.

It’s this tragic irony that colors the series’ major premise. The monstrous kaiju form strengthens Kafka physically, sharpens his senses, and primes him to respond to the threat of the kaiju in a way that their human form never could. Despite this, his motivation to fight against the kaiju is still intrinsically human and deeply entangled with a romanticised vision of what he could be, if he makes it to the top.

This is made apparent through a repeated visual of Kafka’s “dream,” in which he stands triumphantly — in his human form — alongside Mina, his childhood friend and Captain in the Defense Force. The composition of this visual denotes not only how Kafka views himself, but also how he would like to be viewed. There is important detail in the confidence and grace of their stance as he gazes upon the ruined cityscape before him: Kafka wishes to become a heroic—perhaps even “mythical” figure in a world on the brink of destruction, but reality casts him into a farmore inconvenient role.

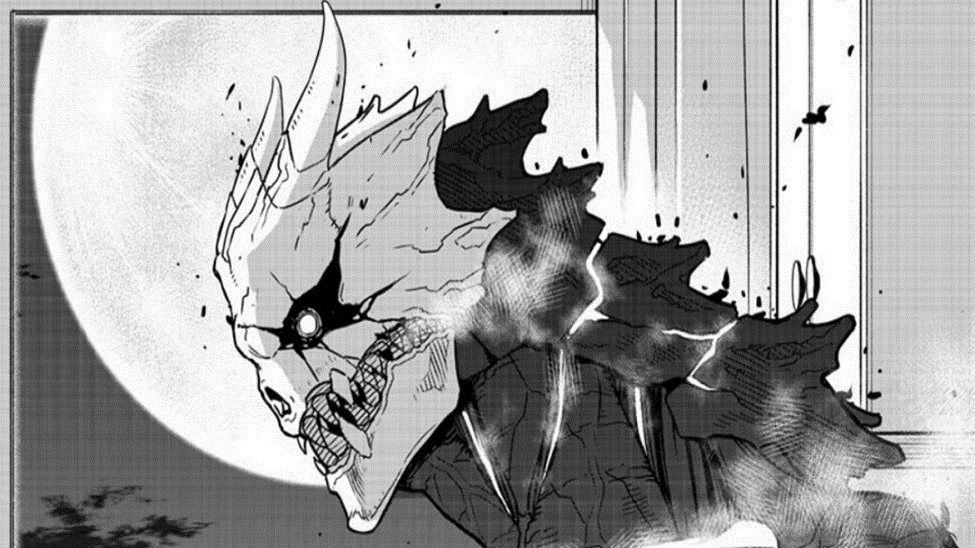

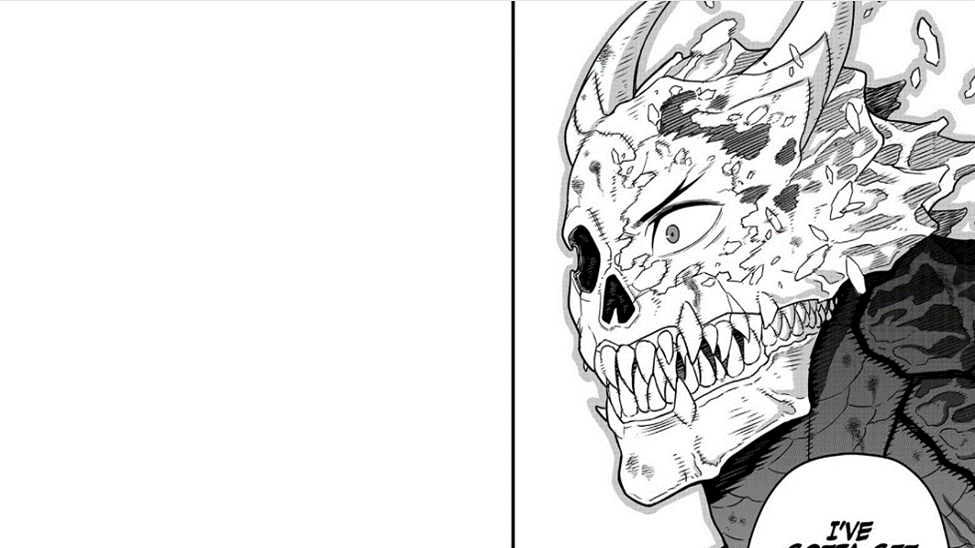

Indeed, Kafka is quickly forced into situations that require him to utilise his new kaiju form to save lives and achieve his goals. From that initial transformation onwards, Kafka is fractured into a being of two distinct but conjoined halves – they are never fully human again, but rarely fully kaiju either. This is something the composition of panels communicates excellently, with many highlighting Kafka’s more human features against their kaiju design. Likewise, the series is not afraid to show the monstrous design of Kafka’s kaiju form, making goofy expressions or adopting a particularly slouched human-like posture. Even when he’s fully human, Kafka’s spiky hair and eyebrows provide the outline of his monster form’s jagged skull. In his monster form, his wide eyes and smirking grin help to communicate the malformed idealism that Kafka is allowing himself to re-learn.

Kafka’s kaiju design is noticeably weathered and ‘broken’, with a hairline fracture that runs through the middle of their skull. In certain scenes where Kafka transforms into his human form, the beast’s skull shatters into fragments, revealing his human face underneath. This not only helps to affirm the idea that Kafka’s kaiju form acts as a form of mask that disguises Kafka’s more bumbling human side, it also symbolically gestures towards the idea that the boundaries between Kafka’s two forms are particularly fragile. Much like the cracks in Kafka’s new kaiju skull, his place in the world has come to be defined by the anticipation of reaching its inevitable breaking point, when the amorphous nature of their identity is revealed to the world and his two forms inconveniently collide.

While Kafka is able to exert some control over their form switches, it’s quickly made clear that the metamorphosis is influenced by circumstance . At times, their monster form suddenly arises in an attempt to mask their human form, whilst at others, the opposite seems to occur. In both cases, though, Kafka’s transformations are sudden, often spurred on out of a particular fear: the aforementioned concern of being ‘unmasked’ in a social context. It’s a phobia that capitalises on the modern idea of ‘impostor syndrome’, and the tendency towards inaction that comes with it. Kafka is finally able to attain his goals thanks to his new amorphous identity, albeit in a way that is always risking his position as a ‘human’. It’s therefore easy to read the kaiju version of Kafka as the one who is helping to achieve heroism that Kafka’s human form is routinely taking credit for. A mistimed transformation could lead to the Kafka being exposed as not just a kaiju, but also as someone unsuitable for the heroic role he wants to shape himself into.

This thematic throughline of Kafka’s “fractured” and “amorphous” identity as being at odds with his dream whilst also giving him the powers to achieve it provides a layered tension that helps to highlight the stakes for the story ahead. Furthermore, it contextualises our understanding of the dream that Kafka clings to whilst all this is occuring by placing it firmly at risk.

Dreaming in a Kafkaesque World

Alongside their ‘amorphous’ nature, Kafka is portrayed as something of an absent-minded dreamer. It’s an idea that further shapes the idea of Kaiju No. 8 as a form of “coming-of-age” story for someone in their thirties. Unfortunately, it’s also a coming-of-age story set in a hostile world, which forces a maximalism of productivity and an allegiance to the Defense Force’s questionably utilitarian views.

The series utilises its secondary characters to advance the audience’s understanding of how Kafka’s worldview has developed, both in response to and in rejection of its world’s status quo. The culture of Kaiju No. 8’s world is defined by determination and drive, particularly through the character of Kikoru Shinomiya. In particular, Shinomiya represents a form of toxic perfectionism, spurred on by the weight of familial expectations. Her mindset and motivations are indicated to the audience through a short flashback, with straightforward dialogue that is juxtaposed with her present day struggles in the Defense Force exam. She carries the burden of being “humanity’s last hope” as the daughter of the supposedly important Commander Shinomiya, and attempts to meet the expectation of being literally perfect by powering through even at the risk of her own life. This is communicated to the audience as a visual parallel between Commander Shinomiya’s eyes in the flashback and Kikoru’s eyes changing to match them in the present day. Kikoru’s eyes become more rounded and precisely lined, which happens only panels later as she makes a final stand against the kaiju.

Over the course of just a few pages, Kikoru’s ‘toxic perfectionism’ is addressed, and begins to paint a picture of the type of people who keep Kaiju No. 8’s Defense Force running. Specifically, it’s those who have already resolved that they can make a difference in this world. Kafka is much less certain of their ability to reach their goals without being exposed, especially with their new amorphous identity. Meanwhile, characters like Kikoru, who feel determined to give everything they have to stop the problem of the kaiju, leaving little wonder that Kafka feels immense pressure to succeed in this ‘final shot’ at his dream.

Through its secondary cast, Kaiju No. 8 also invites us to consider whether faith in the Defense Force is ever well placed. While it’s difficult to tell where the manga might go with this in the future, recent developments in the story have highlighted flaws in the Defense Force’s methods and logic. Several of these passing critiques are loosely reminiscent of thematic ideas in the works of Kafka’s namesake, czech novelist Franz Kafka, whose works made a significant impact on their literary world in their fusion of surrealism and the mundainities of bureaucracy to critique capitalist thought. “Bureaucracy” is the key word here, because while the obvious allusion to Franz Kafka in Kaiju No. 8 is the protagonist’s very own Metamorphosis, Kaiju No. 8’s Kafka is also linked to the author by the illogical, often hypocritical machinations of bureaucratic processes that both orbit.Naoya Matsumoto’s manga is not exactly teeming with scathing criticisms of bureaucracy, but recent chapters have done an effective job of destabilizing the series’ previously rigid definitions of right and wrong. Moreover, the series shines a spotlight on the differences between humans and kaiju, calling the motives of the Defense Force and in particular, their respected Commander Shinomiya, into question.

By the point that Kafka is finally exposed, the fragile and amorphous nature of their new form has already been made clear. As Kafka’s status as a human is debated, weapons forged from kaiju are employed to attack him. As he loses control to his more monstrous side, so too does the commander. The focal conflict becomes more ambiguous as the ‘human-kaiju’ Kafka goes head-to-head with the commander, who also “emits the aura” of a kaiju. Aside from its raw spectacle, the battle serves to call the logic of Kaiju No. 8’s society into question. In particular, it raises the question of whether there is any real meaning to the distinction between human and kaiju in this world that operates solely on their opposition. This is reflected in the artwork, which renders the battle between Kafka and the demonstrably human commander as a battle between Kaiju No. 8 and Kaiju No. 2, even though both characters indisputably retain some element of a human form. It is here that Kaiju No. 8, as series, doubles down on the idea of an existence between the human-kaiju binary, and uses it to highlight society’s illogical methods of classification.

In Franz Kafka’s Metamorphosis, protagonist Gregor Samsa is similarly boxed in by an inflexible capitalist society. The tale sees Gregor transform into a giant cockroach, and the characters that surround him—including all of his close family—are all more concerned about Gregor’s inability to perform his job than they are concerned for Gregor’s wellbeing. In Kaiju No. 8, a similar preoccupation with the protagonist’s “utility” is sketched out when compared to the opposing Commander. The definitions of “kaiju” and “human” are quickly made unstable by the series’ depictions of both, and the difference between a “good” and “bad” kaiju is shown to be similarly weak, as the distinction is shown to be based entirely on how willing they are to fit within the Defense Force’s agenda. As of the most recent chapters, it’s shown that If Kafka can prove his “utility” as a kaiju to the commander as a living weapon, then the Defense Force will seemingly be willing to accept him back into the fold.

Kafka doesn’t really have a choice in accepting these new terms, and his dialogue indicates that he doesn’t want to be regarded as just a living weapon. Now that his fear of being exposed has come to fruition, the pendulum has swung to the opposite extreme, reducing Kafka’s “value” down to his functionality. It’s as dystopian as it gets, but the Commander allows Kafka to hang on to his hope of becoming an officer. At this point, though, it remains unclear as to whether this is a hollow carrot-on-a-stick gesture or a genuine possibility.

Many of Kaiju No. 8’s cast members dream of reaching some abstract peak of self improvement to stop the threat of the kaiju, or to merely pay lip service to the Defense Force’s utilitarian ways, Kafka Hibino, though, wants to reach the top for a reason that is far more naive and selfish: a chance to continue a bond and make good on a childhood promise. The way Kafka clings to a dream that is so far removed from the collective concern of the kaiju is as endearing as it is rebellious, especially as it remains his motivation despite everything he’s been through. Though the series is still in active serialization, Kaiju No. 8 clearly still has a long way to go. Still, with every chapter, it reminds us to keep on dreaming.