What first comes to mind when you hear the word “superhero”? Caped crusaders and friendly neighborhood web-slingers? Many people probably equate superheroes with American comic books and flashy, high-budget feature films. For the manga and anime fan, though, superheroes come in other forms: a bald man in yellow with one hell of a punch, or a young boy with no special abilities in a world where superheroes are the norm.

Superheroes in manga may not yet be as ubiquitous internationally as long-standing characters such as Batman or Spider-Man, but My Hero Academia, a popular series that parodies the American superhero genre, has topped the US comic book and manga charts from as early as 2018 [1] . This trend is so notable that Satoru Saito, an associate professor of Japanese literature at Rutgers-New Brunswick’s School of Arts and Sciences, highlighted “self-reflective parodies of the superhero genre” as a recent trend among Japanese superhero narratives in a 2019 interview.

Of course, Japan has its own culture of superheroes that can be traced back to kamishibai, or paper theater, a form of storytelling featuring painted picture cards that a travelling storyteller would narrate to children. One of the earliest kamishibai series featured a skull-faced superhero Ōgon Bat (Golden Bat) whose 1931 debut even predates Superman’s first appearance in 1938. Another kamishibai superhero character from the same period, Prince of Gamma, was an alien with an alter ego as a street urchin.

With its rich media culture full of superhero characters in manga and anime, American superhero comics themselves have maintained a relatively niche position within Japanese popular culture. Today, only a fraction of superhero graphic novels released in English are translated into Japanese, and superhero films struggle to maintain top positions in the Japanese box office.

The release of Avengers: Endgame, the second half of the final entry in the original Avengers film trilogy, is a perfect example. On the weekend ending on 5 May, 2019, Avengers: Endgame was the number one movie in nearly all nations and territories around the world. But despite only being in its second weekend in Japan, it lost the top spot to none other than Detective Conan: The Fist of Blue Sapphire, the 23rd film in the Detective Conan series, which was already in its fourth weekend [3].

It may be unfair to compare Avengers to Detective Conan. In Japan, manga is an ubiquitous form of entertainment enjoyed by everyone from children to adults, and can be found everywhere from convenience stores to dedicated bookstores. Comic books, on the other hand, were fazed out of newsstands in the 1980s due to poor sales and are now almost exclusively sold through independent comic book stores [4] .

But, as series such as My Hero Academia and One Punch Man attest, the American superhero remains ingrained in the Japanese popular culture consciousness, thanks to adaptations and hybridizations in the form of TV shows, manga, and film.

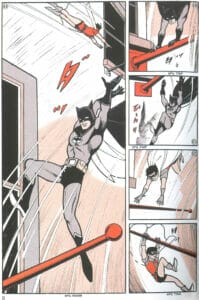

An influx of such adaptations began in the 1960s, alongside the international popularity of the Batman TV show. During this era, kamishibai storytellers were struggling to keep up the popularity of television. In an effort to stay relevant, these storytellers began adapting popular TV shows into kamishibai stories, including the Batman TV show starring Adam West and Burt Ward. Around the same time, manga artist Jirō Kuwata was approached by editors of the Shōnen King manga magazine to produce a weekly Batman manga to coincide with the TV show’s release in Japan.

Kuwata already had experience adapting a live-action superhero TV show into a manga, as he was one of multiple artists hired to draw a tie-in manga for the tokusatsu series Moonlight Mask in 1958. Despite this, Batman would be his first time working on an American comic property. Kuwata originally intended to study the American comics in order to incorporate Bob Kane’s style into his own. He was too busy to do so, though, and the resulting manga was 100% Kuwata [2]. His take gave Batman a bold, striking look that quickly became a hit among non-Japanese readers in the know when it was finally released in English in 2008.

Jirō Kuwata wasn’t the only manga artist approached to draw an American superhero in the 1960s and ‘70s. When entering the Japanese market, Marvel decided to commission Kōdansha to produce manga versions of Spider-Man and The Hulk instead of translating already-published comics into Japanese. Ryōichi Ikegami, an emerging manga artist at the time, was tasked with Spider-Man, and was given Japanese translations of the original American Spider-Man scripts on which to base his adaptation. The resulting character was a Japanese high school student named Yu Komori (his last name, komori, meaning “spider” in Japanese) who gets bitten by a radioactive spider while performing experiments in the school laboratory.

There’s another Japanese version of Spider-Man that’s arguably even more unbelievable: the star of Toei’s eponymous tokusatsu TV series. Running a total of 41 episodes from 1978-1979, this series featured a Spider-Man who received his powers from an alien and piloted a giant robot named Leopardon. This giant robot was the first to be included in a tokusatsu series, after which the idea carried over to Battle Fever J and Super Sentai.

Episode one of Marvel’s 616 TV series, “Japanese Spider-Man” explores the background of Toei’s Spider-Man in depth. The episode offers a glimpse into how beloved the show was in Japan at the time of its release, and features modern interviews with some of the cast. Importantly, the episode explained that this kind of adaptation was accepted at the time, under the condition that it would never be released outside of Japan. Ideally, the restriction would ensure that these works wouldn’t conflict with the image of Spider-Man in America.

Though Kuwata’s Batman and Ikegami’s Spider-Man manga wouldn’t officially make their way to English-speaking audiences until many years after their original releases, the worlds of manga and comics have continued to cross over in various ways. As Daniel Stein notes, with the rise of manga in the late 1990s and early 2000s came an increasing interest in manga versions of superheroes, resulting in multiple superhero manga adaptations as well American manga-style comics [4] .

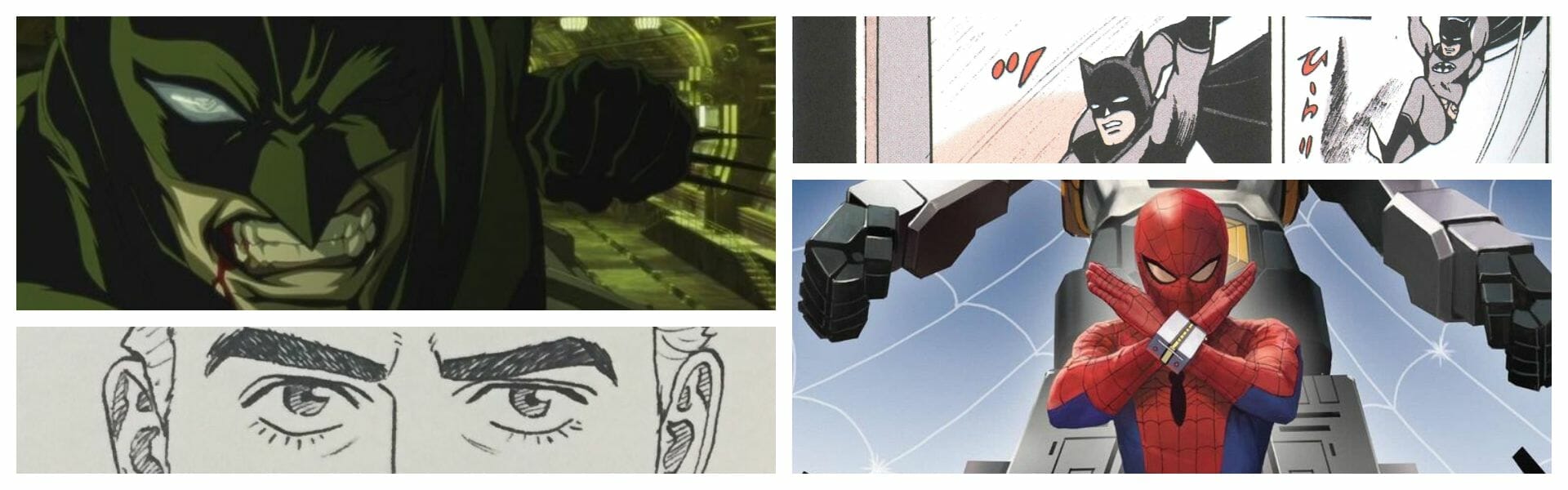

By the late 2000s, Japanese animation studios were taking part in officially-sanctioned collaborative projects. One example of this is Batman: Gotham Knight (2008), an anthology film written by American comic book writers and produced by studios like Madhouse and Production I.G. Unlike early Japanese versions of American superheroes that were excluded from the broader superhero “canon,” this film was intended to take place directly between Christopher Nolan’s 2005 film Batman Begins and its 2008 sequel, The Dark Knight.

Collaborations in the form of crossovers with existing manga series also offered new avenues for superheroes. For example, in 2014, Attack on Titan author Hajime Isayama produced a collaborative comic with Marvel writers and artists titled “Attack on Avengers”. The eight-page comic transports the titular titans from Attack on Titan to New York City, with the Avengers (and a special appearance from The Guardians of the Galaxy) coming to the rescue.

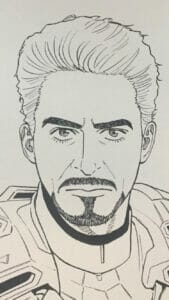

In 2016, Robert Downey Jr.’s Iron Man even had a short excursion into the world of Space Brothers by Chūya Koyama. The 16-page chapter was published in the Japanese women’s lifestyle magazine FRaU alongside a three-part feature titled “A Marvel Primer for Women” promoting the MCU film franchise to the magazine’s predominately female readers. Instead of being a collaborative effort like “Attack on Avengers,” though, Koyama was entirely in charge of the short, titled “#special Tony and Mutta,” which injected Tony Stark/Iron Man into the existing Space Brothers universe.

Such transcultural collaborative projects between American superhero comic creators and Japanese manga artists are a far cry from the Japan-exclusive adaptations of superheroes from the 1960s and ‘70s and the Marvel OEL manga of the early 2000s. Not only are Japanese manga riffing off of classic American superhero tropes to great success with titles such as My Hero Academia and One-Punch Man, but Japanese manga adaptations of popular superhero characters continue to thrive both in Japanese and in English, such as Deadpool: Samurai by Sanshirou Kasama and Hikaru Uesugi and Marvel Meow by Nao Fuji. Indeed, with more and more adaptations, revisions, and collaborations on the horizon, it’s likely that the distinctions between Japanese and American superheroes, as well as the mediums of manga and comics, may become even more blurred.

To learn more about superhero comics in Japan, manga, and collaborations between American comic creators and Japanese manga artists, see “Transnational Superhero Adaptations Between Japan and America from ‘Bat-Manga’ to ‘Attack on Avengers’” by Anne Lee in The Superhero Multiverse: Readapting Comic Book Icons in Twenty-First-Century Film and Popular Media, edited by Lorna Piatti-Farnell.

References

[1] MHA at #2 in spring 2018. Can’t access summer 2018 to confirm its place then but it’s #1 by fall 2018 https://icv2.com/articles/markets/view/41032/top-10-manga-franchises-spring-2018

source: https://www.kotaku.com.au/2019/05/avengers-endgame-doesnt-dominate-in-japan/

[2] p. 4, Kidd, Chip, Geoff Spear and Saul Ferris. 2008. Bat-Manga!: The Secret History of Batman in Japan. New York, N.Y.: Pantheon Books.

[3] p 210, Nevins, Jess. 2017. The Evolution of the Costumed Avenger: The 4,000-Year History of the Superhero. Santa Barbara: Praeger.

[4] p. 151, Stein, Daniel. 2014. “Of Transcreations and Transpacific Adaptations: Investigating Manga Versions of Spider-Man.” In Transnational Perspectives on Graphic Narratives: Comics at the Crossroads. Edited by Shane Denson, Christina Meyer, and Daniel Stein. London: Bloomsbury, pp 145-162.