For the past two years, I’ve been spending Saturday nights online with an anime club based in Maryland. Most of what they watch each week are popular action standbys like My Hero Academia and One Piece. But in the late night timeslots, we’ve been working our way through smaller cult classics: Planet With, Keep Your Hands Off Eizouken! and Akudama Drive. I expected to have to fight to convince my peers to line up older series for those time slots. So I was surprised when a friend in that club recommended Tsuritama, a Spring 2012 classic and one of my favorite anime of the 2010s. I was even more surprised when it won a slot unanimously.

Sometimes a series hooks you, out of the blue, and you find yourself driven to watch the next available episode at all costs. There’s a moment in Tsuritama’s fifth episode, when its protagonist Yuki learns self-confidence on a fishing boat, when I realized the show had me hook line and sinker. I would brave the unsteady WiFi of a Key West bed and breakfast to watch Tsuritama. I would pore through blog posts referencing the Ryujin myth to better understand Tsuritama. I would hunt down recordings from Kuricorder Quartet and hole up inside Tsuritama’s sonic universe. For the rest of 2012, Tsuritama had me dancing to its tune. It’s had a place in my heart ever since.

But when my friends looked for Tsuritama on Crunchyroll, I knew they wouldn’t be able to find it there. When they searched on the internet for a cheap DVD, I knew that the only Tsuritama discs left on the market would be expensive as hell. When they came to me and asked what to do, all I could tell them was the truth. Tsuritama, as much as I loved it, had fallen through the cracks. Whether through alien abduction or licensing hell, the series was nowhere to be found outside rare Blu-rays and torrents. The Tsuritama in my memories, and my friend’s memories, remained vibrant and alive. Outside of them, the show itself might as well be a ghost.

Tsuritama is a show in two parts. The first is a very gentle drama about an anxious teenage boy named Yuki who moves to Enoshima. There he meets a strange boy named Haru, who immediately pulls him out of his usual comfort zone. Haru makes him dance up in front of the classroom, chases him around town and then moves into his house. Most importantly of all, Haru demands that Yuki learn to fish—the fate of the world depends on it! With the help of their jaded classmate Natsuki, a fishing prodigy, they do just that.

The title’s first half is a sports show, as devoted to the intricacies of fishing as Slam Dunk is to basketball or Hikaru no Go is to go. Comics Journal editor Joe McCulloch once said of shounen manga that “no comics in the world love explaining things more!” and this is certainly true of Tsuritama: the characters describe the mechanics of casting, fly fishing and technique in such detail that you could use the series as a guide to go fishing yourself. But Tsuritama is far gentler than the shounen comics average. After all, a lot of fishing involves sitting around and waiting. There’s plenty of time for personal growth: for Yuki to become more comfortable with himself, for Natsuki to learn to compromise with his well-meaning but overbearing father, and for Haru to consider other people’s needs rather than force them to do what he wants.

Tsuritama isn’t just a story about individuals; it’s about communities. Yuki lives with his grandma (one of the coolest in anime history). Haru lives with his sister. Natsuki prays together with his father and sister to his mom’s spirit every night before dinner. Everybody in the world is navigating an absence, a phantom limb they’ve had to learn to live without. But they manage, just like people in the real world manage. Plenty of anime lean on the “found family” trope, putting misfit kids into a situation where they are able to support each other through difficult times. But Tsuritama does one better by building not just a family but multiple overlapping support networks across the island of Enoshima. The characters change not just through their own will, but through their relationships with their friends and neighbors.

I’d still remember Tsuritama fondly if it was just a simple story about kids learning to fish and overcoming obstacles in the process. But it has other fish to fry, as well. Haru is an alien, he’s being monitored by a spy named Akira working for the secret organization DUCK, and the two of them fear a mysterious force sleeping beneath the seas of Enoshima. At first you’d think that Yuki saying, in the very first episode, that “we never expected that we would one day save the world!” is a joke. But a mountain forms out of small unsettling hints: the Enoshima dance, Haru’s water gun, his cool sister who lives in a spaceship, and boats of singing, dancing people out at sea.

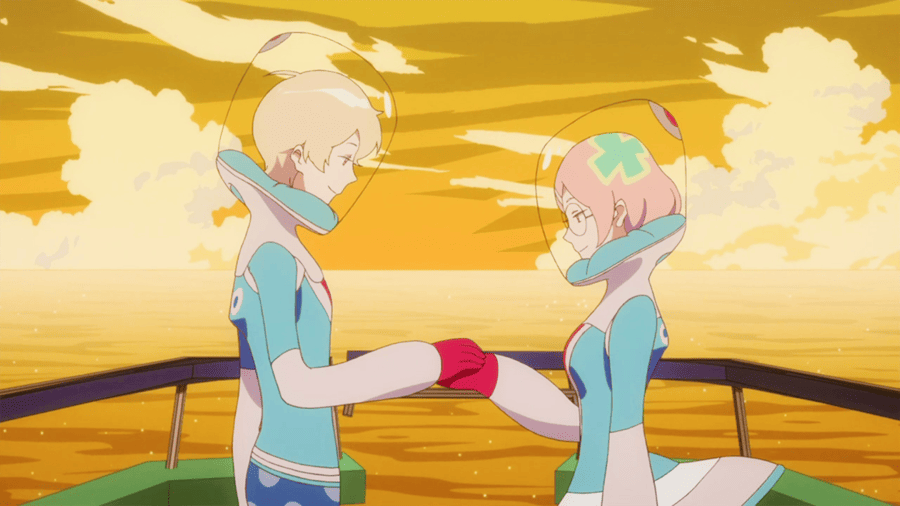

Sooner or later Tsuritama becomes an alien invasion story, a riff on Invasion of the Body Snatchers where the fate of Japan rests on our heroes’ bonds of friendship and fishing prowess. But Tsuritama never loses track of the work done in the show’s gentler first half. The fear and paranoia of the coming apocalypse soon gives way to a veritable Rube Goldberg machine of love and reconciliation, as each member of the cast rejects nihilism to believe in the friends they made out on the water.

Tsuritama’s genius director Kenji Nakamura and writer Toshiya Ono would go on to refine these themes in their later collaboration, the ambitious near-future science fiction superhero epic Gatchaman Crowds. It’s not difficult to look at the shape of Tsuritama and see traces of what would become Crowds: secret organizations bound up in red tape, childlike optimism challenged by stark reality, and a willingness to expand the range of characters typically depicted in anime. Tsuritama also foreshadows the theme of “atmosphere” that would power Crowds’s second season; while the villain doesn’t truly mean any harm, the way in which his powers infect others with groupthink represents a genuine threat.

This dual nature is, in itself, a risk. I can imagine some folks coming to the series for the alien invasion story, only to be bored by the fishing; similarly, I’ve known some viewers who loved the fishing segments but found the science fiction climax to be rushed. Personally, I think Tsuritama’s blend of warmth and suspense makes it a great entry point to Nakamura’s body of work. Not everybody has it in them to brave the visual excess of Nakamura’s earlier Mononoke, or the high concepts of Crowds. The series tells an accessible story with just enough Nakamura weirdness to sizzle, and thus qualifies as an easy recommendation to just about any anime fan I can think of. If only I could offer you a way to watch it! But I can’t.

When I watched Tsuritama as it aired, the series was posted weekly to Crunchyroll. This is no longer the case. As with Gatchaman Crowds, the series was reclaimed by Sentai Filmworks. Yet both seasons of Gatchaman Crowds are available to stream on Sentai’s online service HIDIVE, while Tsuritama is not. DVDs for the title retail for over $100, while the Blu-Rays (which are over $50) are in increasingly short supply.

At this point in history, anime is more accessible than ever before. As well as simulcasting providing seasonal anime to non-Japanese viewers within hours of airing, many older series are available for legal and easy binge-watching. You can watch all of Cardcaptor Sakura on Crunchyroll for free with ads, or pay a monthly subscription to watch ad-free. Other streaming sites like Funimation and HIDIVE offer similar deals. Blu-rays and DVDs (and torrents) still exist, but most fans don’t need them. The days of rooting through YouTube for cut-down episodes of Naruto are over; now, you can just follow the arrows to your next Shonen Jump fix.

Unfortunately, studying the history of other streaming sites results in a less rosy picture. Once upon a time, you could watch just about anything you wanted on Netflix and Hulu. But hosting media under copyright costs money. Some streaming sites chose to give up the rights to properties they didn’t own rather than continue to pay rent; others chose to build new streaming services under their own brand name. Where there was once a manageable number of streaming options, we now have HBO Max, Paramount Plus, and Peacock—and that’s just a handful of the sites calling for subscriptions in the US alone.

These sites also keep a tight hold on the availability of their original material, rarely if ever distributing it on DVD or Blu-ray. While shows like Bojack Horseman and The Haunting of Hill House are available in the United States via physical media, Netflix has so far refused to extend the favor to licensed anime series like Beastars or Little Witch Academia. At the same time, Disney is now fighting to prevent films from their catalog—including former Fox classics like Alien and Who Framed Roger Rabbit—from screening in independent theaters. While the age of streaming started as a vast rainforest of content, it has become the exact opposite: a walled garden built to serve the algorithm and the bottom line of the company, rather than accessibility, curation, or preservation.

Anime streaming sites like Crunchyroll must grapple with the additional reality of licensing Japanese material. The rights to a series won’t last forever—either they have to be renewed, or they fall out of circulation. Some of these shows that slipped through the cracks have been saved by companies like Discotek Media, which seek to preserve older works in the best quality possible. Others, though, have been less fortunate. Tsuritama is one of them. Its time ran out on Crunchyroll, the Sentai Filmworks DVDs were sold off in an end-of-license fire sale, and there clearly isn’t enough desire from the industry side to bring the series back to streaming.

In modern anime fandom, everybody is always chasing the next big thing. Those shows that win, win big; everything else crumbles into dust. If you’ve been watching anime for long enough, you probably have a lot of dust on your shoes. The rampant pace of modern anime production has not only led to stress and burnout in the industry, but made it that much harder for series to stand out from the pack during and after their release. A passing glance at a list of anime released in 2012 reveals countless other hidden gems that have since been forgotten: Blast of Tempest, Sengoku Collection, and Humanity has Declined among others.

What does it matter compared to the upcoming adaptation of manga mega-success Chainsaw Man, or exciting prospects with prestigious, familiar names attached like Naoko Yamada’s new series The Heike Story? Well, it matters to me. Shows like Tsuritama deserve preservation, and titles that are “less successful” deserve that same dignity. How are people supposed to support these works, let alone believe that these shows existed, if they can’t watch them?

I recognize the realities of the current industry, and that at this very moment a decade plus of anime history is making a sucking sound as it flows endlessly into licensing hell. I also recognize that having to jump through a few extra hoops to find a series like Tsuritama is hardly an emergency. But I can’t help but be selfish when it comes to a show that means something to me. I can’t help but be selfish when I remember that before I was recruited to write about anime on Isn’t it Electrifying, founding members Natasha and Steven blogged Tsuritama as it aired. I don’t know what that experience meant to them; it might not mean anything at all. But Tsuritama is part of our shared fate, even if that fate is blog posts about anime dashed off during college over the course of four years. It deserves a wider audience than us ghosts.

If you have your own Tsuritama, you need to hold it close. Anime is transient but the medium has a history. Find that part of history that matters to you and shout it from the rooftops. Don’t let your friends forget that show was alive. If it’s dead, don’t let that memory slip away. Streaming sites will not or cannot do the work of preserving it for us. The fate of those many abandoned worlds is in our hands.