Visual novels are a niche of a niche, a cul-de-sac of Japanese subculture overtaken in recent years by the success of light novels and web fiction. Yet despite the medium fading from popular consciousness, some of its biggest names have broken out and found success elsewhere. Kinoko Nasu currently heads the team developing Fate/Grand Order, one of the highest grossing mobile games ever. Gen Urobuchi has risen to become one of the anime industry’s few high-profile scriptwriters through work like Mahou Shoujo Madoka Magica and Psycho-Pass. Romeo Tanaka’s Humanity has Declined was nominated for a Seiun award, no small feat for a series of light novels. They aren’t the only ones, either. Open up the floorboards of the modern anime industry, and you can find former visual novel writers like Takahiro, Fumiaki Maruto and looseboy toiling away.

Then there are those writers who were arguably just as good as any of those, yet never “made it” outside of the visual novel industry. Ittetsu Narahara is a NitroPlus affiliated writer as ruthless as Gen Urobuchi, but he’s seemingly disappeared since the release of his magnum opus Full Metal Daemon Muramasa in 2009. Hikaru Sakurai, who wrote scripts for the heavily Utena-inspired What a Beautiful series of games at the studio Liar-soft, was announced in 2014 to be involved with the mysterious project Meian no Keruneteru. But the project never materialized, and Sakurai went on to join Nasu’s team of writers on Fate/Grand Order.

There is another former writer from Liar-soft who is now working on Fate/Grand Order, and his pen name is Hoshizora Meteo. His recent credited work includes the script for the anime World Conquest: Zvezda Project, a comedy about a boy who joins forces with a young girl and her found family of villains to take over Japan; Fire Girl, a light novel series that has yet to be officially or even fully translated into English; and Fate/Requiem, an extension of the Fate universe set in a far future where powerful Servants have become an accepted part of everyday life. Finally, there’s Girls’ Work, a collaboration between Nasu’s game studio Type-Moon and the anime studio ufotable… of which there has been no news since 2010. With ufotable’s future now consumed by the extraordinarily popular Demon Slayer, it’s easy to imagine Girls’ Work sitting on the backburner indefinitely.

Why does this matter? Well, without Hoshizora Meteo, this little corner of Japanese pop culture might look very different. After serving as a writer for Liar-soft for several years, he was matched with the character designer and manga artist Tatsuya Nakamura. Together, they released their breakthrough VN in 2002: Kusarihime ~euthanasia~ (translated into English, “Rotting Princess”), a bizarre time loop story about a dilapidated town, the close but corrosive relationships of its inhabitants, and a mysterious phenomena that reduces them to red snow. Kinoko Nasu, Gen Urobuchi and Romeo Tanaka all read and loved Kusarihime, and would go on to produce work that bore Meteo’s influence.

The “Heaven’s Feel” route of Nasu’s Fate/Stay Night told a visceral story of abuse and desperation that challenged the rules of its own setting. Urobuchi’s Saya no Uta built upon Kusarihime’s cosmic mysteries to tell a smaller but even meaner and grosser tale of madness. Tanaka’s Cross Channel is a masterpiece of time loop fiction in its own right, setting up a gaggle of complicated teenagers and then stretching them to their breaking point. These titles were all published shortly after Kusarihime’s release. Nasu, Urobuchi and Tanaka interviewed Meteo and Nakamura for a 2002 fanbook. Its translation is one of the few English-language primary sources we have documenting the industry’s inner workings at that time.

Like many other visual novels of this era, Kusarihime is inaccessible to most audiences. First, because it’s never been released outside of Japan. Second, because it’s a janky PC game from 2002. Third, because being a visual novel from that time released for adult audiences, it includes a wealth of messy content including sex, incest and graphic violence. Despite inspiring three of the best-known writers in the English-speaking visual novel fandom, the game never earned a fan translation (let alone an official one).

All that exists of the game in English are impressions written by bewildered fans, screenshots on the Visual Novel Database and a (subtitled) copy of the opening somebody uploaded to YouTube. Going by those samples, the game has a strong sense of style, using full illustrations and unusual UI design to convey atmosphere. Credit for Kusarihime’s thoughtful presentation can likely be given to Nakamura. But Meteo can draw as well, and it is also possible that his awareness of how the game should look shaped the final product. His future projects share an attention to visual presentation that considers how information is delivered and characters are framed within the scene.

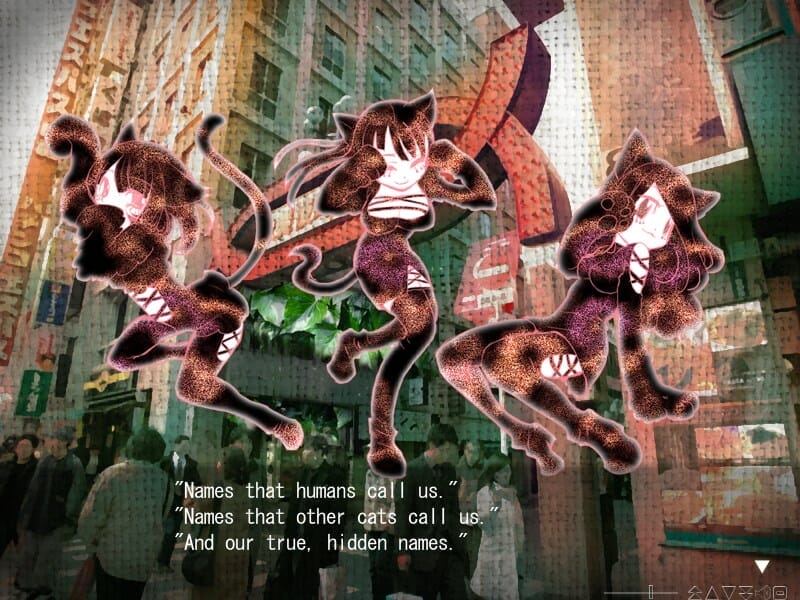

While I have not played Kusarihime, I have played Meteo’s later title Forest, which made an explosive impact on me when I read its English translation in college. It’s the story of five young adults in Tokyo’s Shinjuku ward who are absorbed into a series of games, orchestrated by a young girl named Alice who has the creatures of English literature at her beck and call. Forest name-drops authors ranging from Ursula Le Guin to E. Nesbitt, and features literary cameos that are played both for and against type.

Narnia’s noble mouse Reepicheep earns a starring role, but so does a mournful, chthonic Winnie the Pooh. One chapter mashes up “A Midsummer Night’s Dream,” Peter Pan and the myth of the Tower of Babel. While other games in this genre make you trudge through hours of set-up before reaching the good stuff, Forest has a train turn into a dinosaur—or something equally odd—every twenty minutes.

The structure of Forest is very different from other games of its type. The narration is delivered using both text and voiced lines at the same time, forcing the reader to pay attention to both to receive the full effect. It’s a choice that transforms the process of reading into the equivalent of making sense of different audio tracks piped through separate headphones. It’s a choice that some might find infuriating, and even makes the game inaccessible to those unable to read and hear both tracks. But it makes for a good match with Forest, a story about stories that demands the reader read between the lines.

Additionally, each scene in the narrative is depicted as a “leaf” on a tree, and many can be skipped. All vary in style, narrator and subject matter. Some are character vignettes, others form separate narratives that at first barely seem related to the main plot. Eventually the game will hit you with a big set piece, including some of the most ambitious choice structures I’ve seen in a visual novel.

One is a choose-your-own adventure board game with several possible resolutions. Another is a journey through a series of sky islands that explodes into a labyrinth of choices and dead ends. Rather than expecting you to keep track of your choices to obtain the ending you want, Forest thumbs its nose at any kind of sensible route structure. Even the game’s “bad ending” is designed to ambush you long after you make the fateful decision that triggers it, such that you may not think to correct your mistake until it’s too late.

Forest is also one of the few visual novels of this time period I’ve played that features a cast of adults, rather than high schoolers passed off as college students for the demands of an 18+ rating. Akeru is technically the lead, but the game gives you the choice to begin as either him or Nozomi, a frustrated office worker with a past connection to Akeru and the mysterious Alice. Other members of the cast include Maki, a sensible restaurateur stuck in an abusive marriage, and Kaoru, a young and standoffish medical student who changes dramatically over the course of the story.

My favorite character by far is Amane, a sex worker who’s constantly cracking jokes but is acutely aware that she’s a side character in a fictional tale that she can’t control. There’s a great scene late in the game where, after nearly choking Akeru to death in a fit of anger during sex, Amane shares a cigarette with him on the balcony of her apartment. It’s a strange, powerful, earnest moment of adult intimacy between peers that you rarely see in a game like this.

Years later, I was amazed to find Meteo’s name attached to an anime series, titled World Conquest: Zvezda Plot. Like Forest, Zvezda Plot is the tale of a boy who has an unexpected encounter with a young girl (this one’s named Kate), joins a group of societal outcasts and is drawn into a world that lies just beneath his own. The cast includes Natasha the mad scientist, team dad Gorou and the hilariously incompetent young adult Yasu. Like Forest, Zvezda Plot is structured as a series of bizarre vignettes that build to a grand climax. In one episode, our heroes commit to eliminating all smokers from Japan; another features a local turnip-like plant called udo that can be used to power electrical generators.

The show also features unexpected riffs on pop culture, like an advertisement for a film titled “Hiroshima Dialects Without Honor or Humanity!” Zvezda Plot unfortunately loses momentum at the halfway point, hitting a few episodes in a row that are slower and less imaginative than earlier highlights. But it picks up again at the end, turning the screws so tightly on its found family of lovable weirdos that their happy ending makes you sigh with relief.

With that in mind, we should discuss the elephant in the room. When Zvezda Plot first aired, there were plenty of folks who were disgusted by the skimpy outfits worn by the characters. They were particularly repulsed by Kate, who is way too young to be sexualized in that way. As someone who’s been following Meteo’s work for a while, I can’t help but compare Zvezda Plot to Forest, another story about a man doing the bidding of an entity which takes the shape of a young girl; or Kusarihime, whose protagonist is once again haunted by the ghost of a young girl (who looks like his sister, so it’s incest as well). It’s an archetype that Meteo clearly has some affinity for.

To be fair, each of these three narratives is doing something different with that archetype. Kate’s “evil” organization in Zvezda Plot is really just a big extended family filling in for her absent parents, while the young ghost that haunts Kusarihime represents the tip of a gruesome family tragedy. Forest pulls the biggest gambit of all, drawing parallels between Akeru and Nozomi’s former student-teacher relationship and Lewis Carroll’s infamous friendship with a young Alice Liddell. Alice is the living specter of their affair, a ghost spawned by rumor who gives an adult Nozomi the power she dreamed of as a child and dogs the regretful Akeru at every step.

There are scenes in Forest where Alice (in her form as a young girl) extorts sex from Akeru. The first of these scenes is played as horror but ends with a joke, kicking you back to a checkpoint if you choose to “go inside” Alice. I imagine that most readers would be appalled by this scene; I remember being very uncomfortable when I read it.

At the same time, it’s also a reminder that visual novels, especially adult ones, are a niche of a niche with their own uncomfortably familiar set of uncomfortable tropes. There are games like the Rance series where the number of women the protagonist can sexually assault is a feature on the back of the box. There are games like Wonderful Everyday that cut an in-game image depicting beastiality for English release. Fate/Stay Night was able to find success in the mainstream by jetisoning some elements (like mana transfer via sex) while keeping others intact (like the deeply gross method by which Sakura is abused by her family). By comparison, Meteo’s visual novel work remains wedded to the seediest corners of Japanese VN subculture.

Meteo has been working on the Fate/Grand Order team together with Kinoko Nasu. Nasu’s only ever been effusive in his praise for him, even claiming in a commentary to Meteo’s light novel series Fire Girl that working alongside Meteo permanently changed him as a writer. Yet pinpointing Meteo’s recent credits outside of his light novel projects can be difficult.

Girls’ Work was to be his magnum opus, a co-production between Nasu’s Type-Moon and ufotable. It appeared, from the marketing, to be a spiritual sequel to Forest set in “a Paris of dreams”, a description that had me salivating. But we’ve heard absolutely nothing about it since its announcement. Considering that Type-Moon released its long-promised Tsukihime remake (another VN emblematic of the early ‘00s) not long ago, a visual novel version of Girls’ Work might be possible at some far future date. But who knows when that might be?

Meteo’s recent contributions to the Fate universe are similarly difficult to figure out. Rumor has it that he came up with the original idea for the servant Astolfo, and that he was an uncredited writer for sections of Fate/Hollow Atraxia. He’s reportedly been heavily involved with Fate/Grand Order for the past few years, writing full arcs alongside former Liar-soft writer Hikaru Sakurai. But Type-Moon has been cagey in recent years about which writers are responsible for which story arc, due to past instances of fan abuse. As a Meteo fan (and a Sakurai fan, to be quite honest) it’s frustrating that the contributions of these two writers are hidden deep within the superstructure of an enormous phone game with no clear way of knowing who wrote what.

In the long run, you could say that Meteo’s career was successful. It’s likely that far more people have played his chapters of Fate/Grand Order than ever touched the games he wrote for Liar-soft. So long as Nasu continues to run Type-Moon, I reckon that we’ll continue to see work that bears Meteo’s touch. But as a fan of his earlier work, I can’t help but wish that one day Meteo is granted the same prestige that, say, Urobuchi currently possesses in the anime marketplace. Meteo’s harder to fit into a box, but that’s precisely what makes him a great writer within his niche. His stories aren’t always coherent or consistent, but they always take you outside the box of genre formula to a wilder and woolier place.

But what right do I have to say that, really? I’ve never read his work in original Japanese. Even with the handful of information I’ve dug up, there’s so much I still don’t know. To be a fan of visual novels when you don’t know the source language is always to be haunted by the ghosts of games you might never play, and stories you’ll never experience in their proper context. I don’t know if the truth of those buried stories might measure up to the Meteo in my head. I don’t even know whether he’s better than other forgotten writers that visual novel fans swear by, like Shuumon Yuu or George Jackson. Perhaps it’s all just coal. But who cares if art is trash or treasure, so long as it leaves a mark? As Akeru once said, “only children talk about reincarnation and eternity! Those things don’t even sell at Comiket!”