Editor: Madeline Blondeau

Content Warning: Contains imagery that includes graphic violence, gore, and body horror.

Old-school anime fans know just how weird the medium can get. There are a massive number of older titles you’d find at Suncoast or Blockbuster that were noteworthy only for how shocking they were. Still, no matter how schlocky they got, there was immeasurable creativity devoted into every frame of animation. Even something made in bad taste can have artistic merit.

Among these titles, there is Genocyber.

Genocyber is infamous. Most people who have seen it can agree that the anime is trashy and mean-spirited. It reflects a nihilism that’s at once deeply disturbing and incredibly eye-catching. While the OVA is brief, it does a lot with its run-time, immersing you in a world of psychic battles, grotesque body horror, and human savagery. But there’s one key flaw that ruins the whole affair: despite hating humanity, the show lacks a sense of humanity. This fascinating weakness makes Genocyber a perplexing failure. It came so close to being meaningful, but a foundational flaw ruined it.

What is Genocyber?

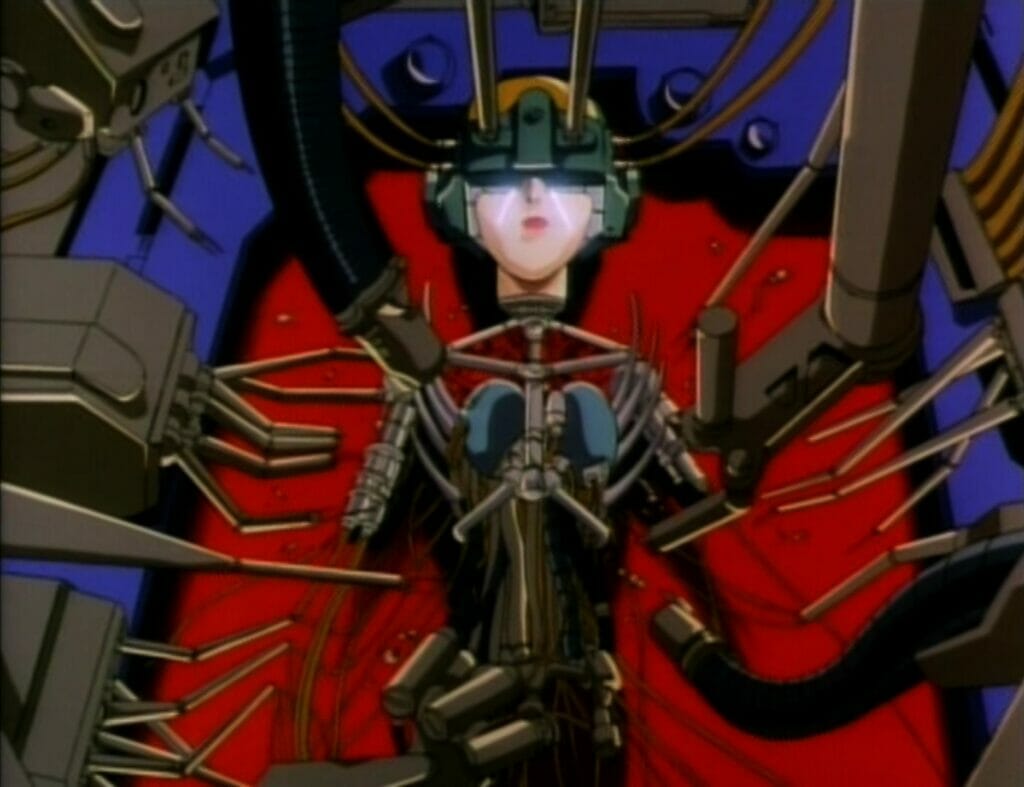

Younger fans might not know much about Genocyber. Starting life as a brief manga by Tony Takezaki, Genocyber tells the story of the titular bio-technological machine – or Vajura. Genocyber is created when two twin psychic sisters, Elaine and Diana, are fused in a pseudo-technological, pseudo-supernatural ritual. The two girls are studied by a Japanese super-corporation known as the Kuryu Group (mistranslated occasionally in the dub as the Kuron Group). A mad scientist working for the Kuryu Group sets out to hunt down Elaine after she escapes.

The manga lasted only a single volume, outlining the start of what appeared to be an epic saga. The anime continued the narrative, showcasing how the creation of Genocyber devastated both the cultural landscape of this world’s present and its far-flung future.

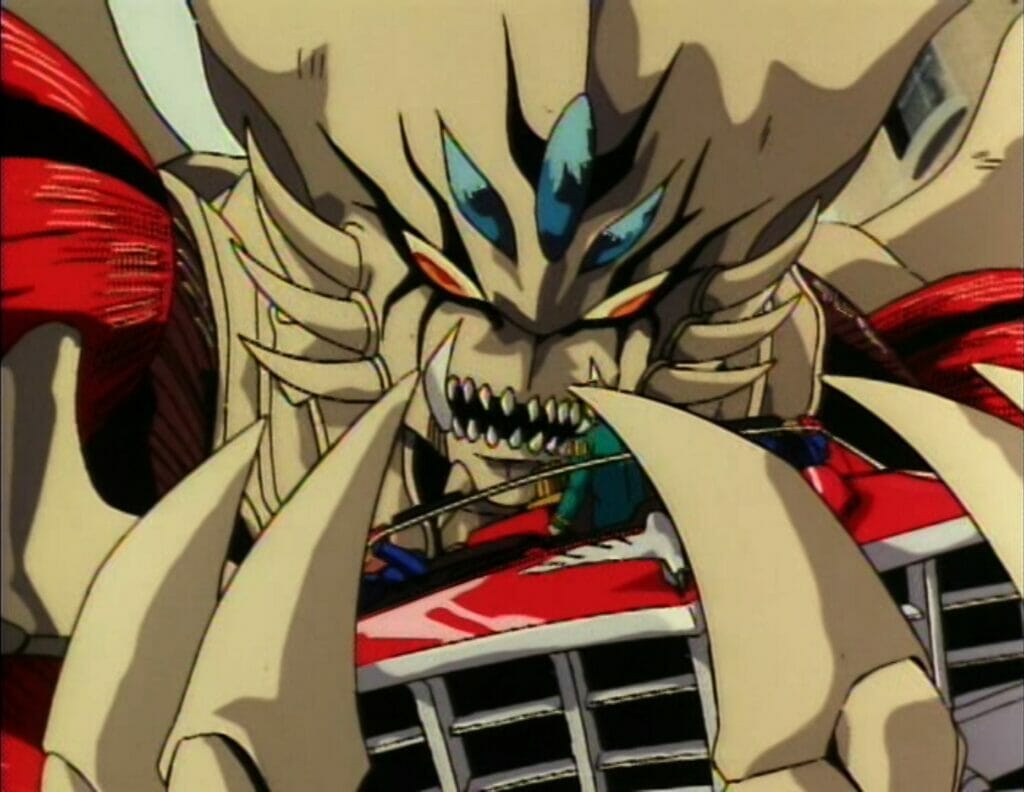

At first glance, Genocyber appears to be a riff on shows like Guyver. The titular Genocyber and other Vajura—humanoid bio-androids— are a grotesque mix of body horror and cyberpunk that would be at home in Yoshiki Takaya’s sci-fi classic. . Meanwhile, the world is so cynical and cruel that it could be compared to that of Go Nagai’s Devilman manga. It’s difficult to pin down what genre Genocyber belongs to, though, because it feels like the story changes greatly from episode to episode.

The first episode serves as an adaptation of the manga, climaxing with Diana and Elaine first fusing into Genocyber and combating bio-cybernetic assassins. We learn that Diana has complicated, self-contradictory feelings towards Elaine, including jealousy, admiration, and loathing.

None of this is fully explored, as the episode concludes with Elaine triggering a wave of destruction after discovering her only friend, a boy named Rat, was killed either before or during the fight.

From there, the subsequent installments track the worldwide impact of Genocyber’s awakening, as society is thrown into chaos. Countries turn against one another, with the United States believing Genocyber to be some superweapon developed by the fictional nation of Kairan.

We learn here that the actions conducted by the Kuryu Group in the prior episode were spearheaded by a rogue agent, and, so, the Kuryu Group is now trying to clean its mess. They send a new Varja after Genocyber, along with several scientists, on an airship bound for Kairan. However, Elaine (who has completely consumed Diana and now has a cybernetic body for unknown reasons) re-materializes on said airship.

From there, the sheer presence of Genocyber drives everyone around Elaine into utter madness. The third episode ends with Kairan being completely obliterated by Genocyber as a result of her battle with the Varja.

The final arc of the story is set centuries later, after Genocyber has ravaged human society. The Kuryu Group is obliterated in the opening sequence by Genocyber.

In this future, only small city-states remain. The episodes center on a new cast of characters who uncover the lost Genocyber as it is reawakened.

From this description, Genocyber sounds like a must-watch cyberpunk anime. So why is Genocyber rarely recommended when discussing classic cyberpunk anime?

Genocyber and the Systems of Control

One of the elements that continues to cause frustration when analyzing Genocyber is how close it comes to something great. From a surface-level read, one could say that it’s similar to Akira.

On a superficial level, one can compare the two works visually. Both are cyberpunk stories that use body horror to distress and disturb the audiences. Likewise, both showcase truly horrific material from the perspective of outcasts from society.

In the case of Akira, we experience the film from the perspective of disgruntled biker gangs and rebels. In Genocyber, meanwhile, we see the story unfold from the perspective of the disenfranchised. Elaine and those who she encounters over the course of the initial three episodes are either outcasts from society or, due to their state of mind, are deliberately ostracized. The third episode ends with Myra, a young female doctor who befriends Elaine, being driven to a state of total delirium due to her encounters with Genocyber and the Vajra.

Both works center on powerful capitalist organizations exploiting the youth in gruesome militaristic experiments. Both culminate in said experiments causing mass destruction, and both showcase how that destruction causes society as we know it to break down.

What separates Genocyber from Akira, however, is how the story chooses to explore these ideas. Akira deliberately shows teens as being essentially powerless in an oppressive society to showcase how they channel that frustration. Tetsuo destroys, while Kaneda and the others attempt to either restore or recreate the world in order to protect what they hold dear.

In Genocyber’s case, very little of that train of thought is put into the OVA’s characters and what their struggles mean in the face of the conflict. We see Rat, Elaine’s friend, be treated kindly by Elaine, only for him to be savagely molested and, eventually, killed as an unimportant casualty. In comparing him to Akira, he bears similarity to the character Kaori, except in one key way: Kaori is a fully realized character, not an object that spurs Elaine into action.

Problems with Characterization

It’s in the realm of characterization where Genocyber fails hardest. People act as they need to in a given moment. Motivation usually boils down to simply “survive,” “greed,” or “anger.” Often, anger and sexual desire are integrated in an implausible way. The Vajra who hunt Elaine down in the first episode, for example, when blending their physical bodies into one bio-android, almost seem to draw erotic pleasure from the experience. Why? Who knows? Maybe they’re Cenobites straight out of Hellraiser.

When characters need to act irrationally, the plot just drives them insane. The second and third episodes feature characters whose arcs culminate in “They go crazy” or “They get paranoid someone is out to get them, and they thus do something self-destructive.” None of these arcs tie into the greater themes of systems of control exploiting the disenfranchised to reach their own ends. After all, things go wrong not because people are awful, but because individuals are just too self-interested or paranoid to handle stress.

The closest we ever see the system to directly causing harm as a part of its systemic force is in the first episode, when the Kuryu Group massacre everyone in a hospital and dissect them like frogs. The scene is violent and dehumanizing, showcasing how indifferent organizations can treat people like animals – to be disposed of at the earliest moment of inconvenience.

The problem is that any pretense Genocyber gives at deeper meaning is lost when there’s no follow-through with the characters.. The characters are so one-note that we never really gain a clear understanding as to why the Kuryu Group would even want to create Genocyber or Vajra. The rogue agent and his underlings have even less motivation to act. They gain nothing from their actions, and just come across as evil for the sake of being evil.

Complicating this matter is the rotating cast of characters. Very few people live long enough in Genocyber to actually have a meaningful arc. Even the anime’s central characters, Elaine and Diana, have minimal characterization. Diana is seemingly absorbed after the initial episode, and Elaine just sort of exists for other characters to project onto.

This is best seen with Myra, whose entire unraveling grip on sanity shows her latch onto Elaine. Myra lost a daughter named Laura, and comes to see Elaine not as a person, but as a replacement for said daughter. The second arc ends with Myra begging Elaine – who she fully believes to be her daughter – to rescue her from the Hell that has become her world.

Myra is, ironically, the most poignant character in the anime. But because her arc is so disconnected from everything else around her, she feels fairly insignificant in the scheme of the story. In a way, this encapsulates Genocyber’s whole method of establishing characters: people are meaningless and have little impact on the scheme of the plot – except in death.

This is also why it is so difficult to explore the final arc of the OVA in any meaningful capacity. The episodes are far more character-focused, with very little effort being placed on establishing the rules of the new future. However, these characters are utterly insignificant in the scheme of Genocyber’s overarching plot.

We center on a new group of characters. Ryu and Mel are a loving couple. Ryu wants to earn money to pay for a surgery that will cure Mel of her blindness. However, all of that is sidelined when the city’s mayor turns his troops on the Genocyber.

This arc does present a religious cult that sees Genocyber as divine punishment for humanity’s cruelty, but very little is really done with this idea, especially considering that we already know the human origins of the being. The episode does end with the trademark destruction the Genocyber anime is known for, as well as a strange hint of renewal, with the Genocyber restoring Mel’s sight and Mel giving birth to someone who may or may not be Elaine and Diana’s reincarnated self.

That said, the problem here is that, again, the characters are disconnected from the themes of the story – because the cast members have very little going for them in terms of depth. Every character exhibits one surface-level motivation: Ryu wants to help Mel, Mel wants Ryu, the cult worships Genocyber, and the mayor wants to maintain control. The characters are unremarkable, which makes it hard to engage with any ideas of deification or systems of control presented in this arc.

Even Genocyber is robbed of its humanity, being mostly dormant, with vague hints of its fused intelligences. We see an image of Diane and Elaine, but little sign that they’re anything more than ghosts, entirely disconnected from the titular Vajra.

The Pace of Violence

Genocyber may be a flat series with little dimension, but it has heaps of violence. It’s the brutality, actually, that earned this anime a legacy. Sure, its characters may not be deep, but they’re full of guts, and the animators are sure to show ‘em to you.

Much of the series focuses on people being cruel to one another. This cruelty does help inform the plot. People use violence to enact sociopathic, enigmatic ends. The creation of the Vajra and Genocyber is fueled by violence.

Much of this violence is incredibly animated. Of particular note is the battle at the end of the first episode, where we see a grotesque fusion of two bio-androids, followed soon after by Genocyber ripping the creature apart. This sequence features incredibly fluid animation. It’s breathtaking and beautiful in how grotesque and dehumanizing it all is.

But the ultimate question that undercuts all that violence is “Why?”

Why does anything in this show happen the way it does? Functionally, the show shows violence to entertain, and, to that end, it pushes all other conventions of storytelling out of the way so that it can get to the violence as quickly as possible.

Genocyber, in its first two arcs, is in constant motion. Whereas most stories stop and linger on scenes or motivation, there is very little stillness in Genocyber. As a result, every scene exists as a bridge to the next horrific image. People need to be carved open in a hospital. Two bio-androids need to merge. People on an airplane need to have horrific hallucinations. A country needs to burn.

All of this happens in rapid-fire sequences where very little motivation is given for anything. Without any tangible understanding why events are happening the way they are, nothing means anything. We don’t ever get a chance to linger on feelings or come to understand them. We barely linger on them long enough to even know they exist.

The result of this lack of characterization is clear. We see characters as sacks of meat to be eradicated in brutal fashion. As a result, we can’t become attached to any of them. We just wait for their inevitable destruction. The characters mean nothing.

The only character to be clearly defined in the whole series is Myra, the scientist who sees Elaine as her daughter. We understand her madness, if even a little bit. As a result, her madness is the closest the series comes to being horrific. It’s far easier to understand Myra’s grief than, say, the weird instincts of an insane, rogue scientist.

When we get to the final arc, the violence dramatically slows down. As a result, the question on your mind when watching is “Okay, when is it going to get violent again?” The show puts aside its barrage of violence in order to showcase character writing…only to reveal that whoever was writing this script really didn’t care about writing people at all. Just planning sequences of gore and brutality.

As a result, the final arc of Genocyber is almost painful to watch. You end up questioning if Genocyber ever could have been good with character writing this inept.

Was Genocyber Almost Good?

It’s difficult to determine whether a show could have, in some other world where decisions were different, been good. The manga remains incomplete, and the OVA seemed unfocused from start to finish. Perhaps with a better base work, the series could have been better.

It’s hard to watch Genocyber and not think, ironically, of another ultra-violent anime known for its sloppy storytelling: Elfen Lied. The Elfen Lied anime, in many respects, has many of the same problems mentioned above: a priority on violent setpieces delivered at the expense of story cohesiveness. But where Elfen Lied distinctly succeeds and Genocyber fails is in its characterization – at least, in the anime.

Elfen Lied’s manga struggled to balance ultra-violent horror with sex comedy, resulting in an uncomfortable tonal clash between bloody murder and wacky hijinks. This also resulted in characters acting wildly inconsistent depending on the story’s needs. The anime’s director, Mamoru Kanbe, wisely chose to hone in on the horror and consistent characterization. This resulted in one of the series’ most disturbing scenes—the murder of Lucy’s puppy—becoming so powerful.

If Genocyber had a crew who understood characterization and character writing, the OVA might very well have been enjoyable. The violence would have had an impact. The themes might have been grounded. Elfen Lied needed an anime director like Kanbe, who previously worked on episodes of Cardcaptor Sakura and would go on to helm The Sound of the Sky and The Promised Neverland.

Meanwhile, Genocyber was directed by Koichi Ohata. More than that, it was Ohata’s directorial debut, after working as a designer on Gunbuster and Angel Cop. It makes sense that his priorities would be on visuals rather than storytelling. Still, given that his most recent credit is work on Redo of Healer as a storyboarder, it’s clear that Ohata remains comfortably in the world of nihilistic violence to this day.

There might be a world where Genocyber is good. Until we find that world, however, we’re left with a cautionary tale about how a sci-fi saga can fall apart without characters and horror can feel impotent without a sense of meaning behind the gore.