Content Warning: The following article contains mentions of sexual assault. Some images contain depictions of violence.

Eiichiro Oda’s One Piece is one of the biggest stories of this generation, taking 25 years and counting to unfold a massive narrative unlike any other. Comparing it to other seminal epics, like The Lord of the Rings or The Odyssey, is not unheard of given its size, narrative structure, and expansive lore. In fact, One Piece shares a lot in common with classic Greek epics – specifically those about a hero’s journey. For so long, the Greek epics have served as a blueprint for modern storytelling, as seen in One Piece. This goes beyond just the story structure, though, as many classic characters and their respective archetypes are seen today in pop culture, whether that be with literal interpretations or with modern reimaginings. It’s through these reimaginings that audiences see how far both storytelling and civilization have come. They also see how a story told centuries ago can still have an impact on society today, which will likely be the case for One Piece given its legacy today.

When looking at One Piece and how it approaches real-world myths, Boa Hancock is the best example of how Oda keeps Greek mythology alive with a modern twist. In this instance, the Medusa myth serves as inspiration for Boa. Like many feminist critics and storytellers before him, Oda reworks the classic myth to elevate a female character once seen as just another monster. Medusa has had a remarkable transformation over the decades, and Oda keeps said evolution alive via Boa Hancock.

Introduced in Episode 409 of the One Piece anime and Chapter 516 of the manga, Hancock is one of the Seven Warlords of the Seas and ruler of Amazon Lily, an island paradise of women. Early on, there are similarities between her and the Greek mythical figure Medusa given Hancock’s abilities to turn people to stone, her snake motifs and her backstory crediting a gorgon for her powers – even though she actually received her abilities from a Devil Fruit. Medusa is an obvious inspiration behind this character while the Greek myths about the Amazons are the inspiration for Boa’s home; however, these are more than just inspiration.

Oda is practicing – in his own way – the oral traditions of ancient Greece, which often saw countless myths passed down verbally, thus leading to variations of the same story. While Oda is writing down One Piece, he is telling his own version of the Medusa myth and building off of the multiple interpretations of the character that have emerged over the centuries due to her ever-changing story.

Due to the nature of Greek oral traditions, there is no definitive iteration of a myth, and that carries over to Medusa. In some instances, as reported by the Metropolitan Museum, she is a woman seduced by Poseidon, and the two have sex in Athena’s temple. Because of this, the goddess turned Medusa into a snake-like monster as punishment. Other iterations, as reported by Vanderbilt University, see Medusa as a victim raped by Poseidon but punished nonetheless. It’s this latter interpretation that has been latched onto by my feminist critics, and it paved the way for the reclamation of Medusa, as she is now well-regarded as a tragic figure at the hands of the patriarchy as opposed to just another monster. Along with that, it is this iteration of Medusa that most closely resembles Boa Hancock.

As time goes by, as reported by Vice, Medusa has become more of a tragic hero and muse than a monster, as seen with the countless art pieces she inspired, as well as how her image is used as a symbol of protection and liberation. The Laugh of the Medusa by Helene Cixous, for instance, directly calls out how man has painted Medusa out to be a monster in order to condemn femininity. This is just one of many readings where the Medusa myth is re-examined with a female gaze, thus leading to tale about the demonization of a woman’s body, the systemic silencing of women, and the struggle of sexual assault survivors. Hancock continues this tradition as well, with Oda telling the story of a woman put in a similar situation as Medusa and eventually using the myth itself as a means to empower and protect herself and other women.

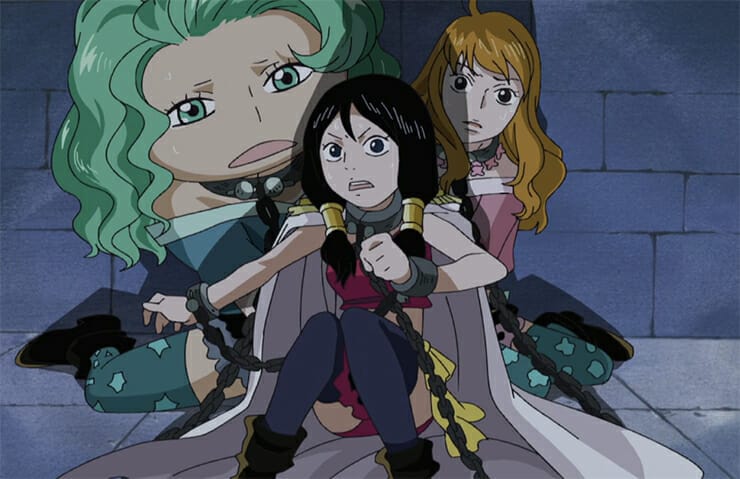

As a child, Hancock is sold into slavery with her sisters. Here, men take advantage of Hancock and further punish her by forcing her to eat a Devil Fruit. Said Devil Fruit, however, gives her the ability to turn anyone attracted to her to stone. Where Medusa was cursed to be so horrific that her gaze turned men to stone – an ability that has been interpreted by some as a means for Medusa to defend herself – Hancock has been cursed with the ability to turn those who lust for her into stone.

Like Medusa, this is a curse Hancock reclaims as her own to defend herself. More specifically, she is taking advantage of her enemies’ objectifying thoughts about her to ascend to power, make a name for herself and protect herself and her loved ones. As a woman who was sold and treated as an object since childhood, this ability to punish those with the capacity to treat her as such again takes on a deeper meaning. Hancock turns what was used against her as her own strength and reclaims her narrative and agency in the process.

Along with that, Hancock’s story is the natural progression of the Medusa myth. With the Medusa myth being reimagined over the centuries, it is no surprise that this would continue in pop culture, as has been the case for other myths – as seen in books like Circe, plays like Hadestown and webtoons like Lore Olympus. Along with that, the Medusa myth has seen the titular character evolve from monstrous villain to tragic victim. As more time has gone by, it is inevitable to see the Medusa myth undergo yet another transformation – one where she is not the victim; she is the hero.

Where the original myth itself has been reclaimed by feminist critics to be an examination of a woman’s suffering, exploitation and abuse, she is still defeated by Perseus in most versions of the literal myth – beheaded and once again used for the desires of a man. Hancock, on the other hand, escapes her abusers and uses the powers she was cursed with to thrive as the only woman Warlord in One Piece. Along with that, her Warlord status allows her to maintain a paradise for women – one free of the dangers she and her sisters suffered as children.

Hancock’s origin and what she’s done with her Devil Fruit abilities take the Medusa myth to another level, one where the Medusa figure is not just a survivor – she is a conqueror. On top of Hancock’s story metaphorically building off of the Medusa myth, Hancock literally takes this story into her own hands and reworks it to benefit herself. After escaping slavery, Hancock and her sisters need a cover story to protect themselves and maintain their public image, otherwise, they risk enslavement again and leave Amazon Lily vulnerable. This is where the Gorgon myth comes into play again.

As slaves, the Boa sisters were branded on their backs, so if anyone sees these marks, the sisters are at risk once more. To avoid this, Hancock and her sisters claim they fought a gorgon and defeated her, but it came at a price. While Hancock claims she got her stone abilities from the gorgon and her sisters got their snake abilities this way as well, they were also cursed with the gorgon’s eye on their backs. Because of this, no one can stare at their exposed backs otherwise they will turn to stone. This is not true, but the gorgon myth seems to be known well enough in the world of One Piece that Hancock can string together a believable lie out of it. Like Oda, Hancock practices Greek oral traditions in her own way, expanding on the Medusa myth while also defending herself and her sisters.

With over 1000 chapters and counting in One Piece, there are many myths to unpack in the manga and its respective anime, but it’s the Medusa myth and its relation to Hancock that perhaps highlights how Oda continues Greek oral traditions the best. He may not be sharing the story of One Piece orally, as would have been the case centuries ago, but he is passing down this myth through his own lens with Hancock’s origin, abilities, and story arc. Along with that, he demonstrates the practice of Greek oral traditions in the text itself with how Hancock takes an age-old myth about the gorgons and reworks it to create a new myth about herself.

Oda’s Boa Hancock is more than just a reimagining of Medusa. She is proof that Greek myths continue to grow and change to this day, with the Medusa figure evolving from a condemned woman who should be punished to a survivor who fights back and thrives thanks to the abilities that were originally meant to punish her. Oda’s Hancock is one of many Medusa figures reclaiming the myth for modern women, and she is a character who highlights how myths are always fluid and change depending on the times and the storyteller.

Edited By: Nicole Mejias