Table of contents

Introduction

Like NFTs and cryptocurrency in recent years, much of the talk surrounding artificial intelligence (AI) has amounted to little more than heavily hyped marketing campaigns disguised as good-faith discussions. Yet seemingly overnight, AI has invaded nearly every industry, causing a litany of negative repercussions. This rapid proliferation is fueled, in part, by our desire to find quick, easy answers to even our most consequential queries. Conceptually, AI has been the subject of science fiction for decades; for much longer still, automation in some form or another has been the goal of societies looking to increase efficiency and decrease reliance on the human body. The craze of the early 2020s usually refers to chatbots connected to Large Language Models (LLMs) like ChatGPT, which was released by OpenAI, a company that defines AI as “highly autonomous systems that outperform humans at most economically valuable work.”

However, the “outperform” part of this definition has yet to be realized. Worse than consulting any fortune cookie, Magic 8 Ball, or horoscope, it’s not that AI responses are vague or irrelevant—it’s that they’re often entirely incorrect. Writing for the Associated Press, David Klepper reports that OpenAI itself “has acknowledged that AI-powered tools could be exploited to create disinformation” on every conceivable topic. According to Klepper, so far this has included information about vaccines, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the insurrection that occurred at the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021.

Writing for Fortune, Sage Lazzaro covers the so-called “hallucination problem” endemic to ChatGPT and other generative AI tools; namely, that they just make stuff up. Unfortunately, as Lazzaro notes, this slightly inconvenient fact has not stopped profit-driven enterprises from hurriedly adopting this largely untested technology for fear of missing out on the next big thing:

When OpenAI released ChatGPT, it opened the floodgates. Google, which had been holding back on productizing its competing tech over concerns it gave too many wrong answers, released Bard to avoid falling behind and is now experimenting with how it can recreate its search business in the image of generative A.I. Many companies quickly followed suit, rewriting their product roadmaps to meet the new generative A.I. moment.

There are a number of interrelated cultural reasons for this technological overhaul. For one thing, AI is a useful tool if the objective is to refrain from paying—or even interacting with—other human beings. This can be very attractive to opportunists of all stripes looking for shortcuts: whether it’s writing, drawing, or composing music, AI has been enthusiastically embraced by those lacking the inclination to spend their time and money developing actual skills. Comparable to the undercurrent of resentment fueling purchases of crypto tokens as a way to somehow stick it to Wall Street, it is not hard to see why AI appeals to those with disdain for expertise: as comedian Sarah Silverman and many others contend, it unceremoniously pulls from the copyrightable work of others. By extension, any defense of generating content using AI almost necessarily requires a devaluation of human effort; it regularly casts actors, writers, and other talented individuals honing various crafts as elitists who need to be taken down a peg or two, regardless of their accomplishments or status.

Opposition to AI has even been characterized as a form of ableism. The corporate realm has been a bit more tactful, if not less subtle. In a write-up of Sudowrite (a subscription-based service advertising AI as a tool for writing fiction), Josh Dzieza of The Verge describes writer’s block as a “luxury” that some independent authors simply cannot afford; writing for Bloomberg, Brad Stone suggests that such tools might “save” us from “the drudgery” of writing. In unvarnished social media posts as well as polished puff pieces, artistic expression is reframed as menial output while the creative process is treated as though it were a detestable chore.

But AI is not exclusively the domain of the envious or the spiteful. Taking advantage of our continuous quest for time-saving measures, AI insidiously indulges our laziest tendencies and encourages bad habits. Even professionals who ought to know better have been enticed by the prospect of letting a mindless machine do their work for them. Reporting for CNBC, Dan Mangan details how lawyers with years of legal experience were sanctioned for using ChatGPT to file a nonsensical brief—complete with fake citations pointing to non-existent cases—on behalf of their client. One can envision similar catastrophic results cropping up in other fields as time marches on. Sadly, we need not imagine what this kind of damage looks like in the world of translation: writing for RestofWorld, Andrew Deck describes how the asylum claim of a refugee from Afghanistan was denied because of inconsistencies between her initial interview and her subsequent written statements. The discrepancies arose due to faulty machine translations, which Deck says have quickly become a serious issue in multiple industries:

In 2016, Google launched its first neural machine translation system. Today, when subtitling films for streaming companies or drafting documents for law firms, some of the most established global translation companies use neural machine translation in their workflow in an effort to cut costs and boost productivity. But like the new generation of AI chatbots, machine translation tools are far from perfect, and the errors they introduce can have severe consequences.

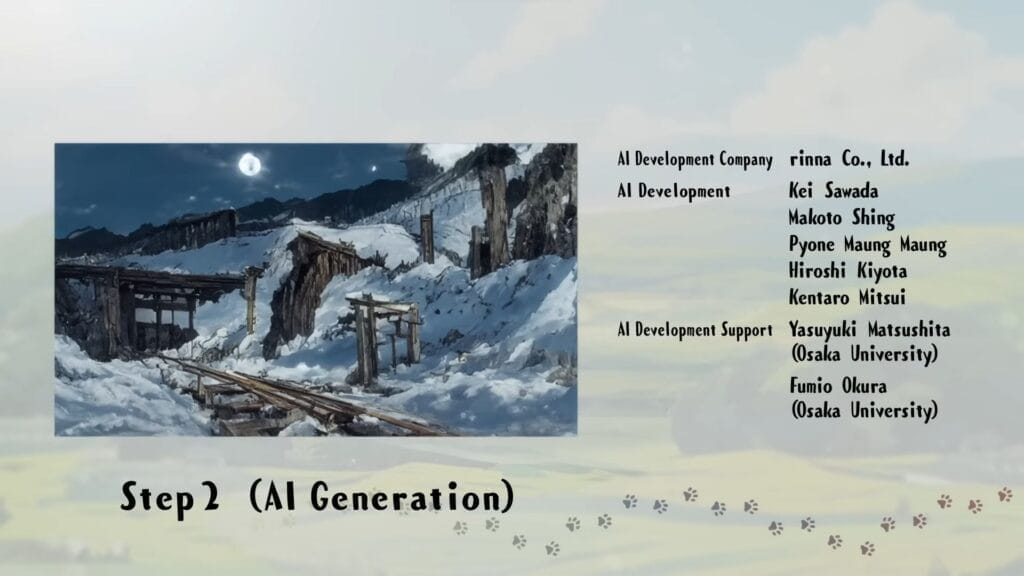

This begs the underlying question of the present case: What will the push for increased implementation of AI do to anime and manga? We already have precedent for background artists being replaced in Japanese animation: reporting for Vice, Samantha Cole shares how Netflix’s animated short film The Dog & The Boy (2023) uses AI-generated artwork. Meanwhile, as featured in Kizuna, an AI system called “Mantra Engine” has already been adopted by several companies in Japan and elsewhere in their attempts to streamline the translation process of popular manga titles. Although such efforts emphasize the need for timely releases to offset labor shortages or combat piracy, they raise significant ethical concerns as they bring about powerful economic consequences.

The Japanese entertainment industry churns out innumerable international commodities. For those who are not fluent in Japanese, translation is a vital component to the consumption thereof; it is also essential for Japanese companies who are heavily reliant upon foreign sales of their products. For countless fans around the world, their enjoyment of animation, comics, light novels, and video games requires the work of dedicated, qualified professionals making otherwise inaccessible artwork understandable. Three of these individuals have graciously agreed to share some of their thoughts on this subject with Anime Herald so that every fandom predicated on Japanese media might maintain an awareness of these developments. By learning what they can do to support the people working to bridge the gaps between linguistic barriers, they can (hopefully) prevent official releases of their favorite franchises from slipping below acceptable standards of quality.

The Role of Translators

We all have a general idea of what translators do—translate, of course! But to learn more, we need to hear from those in the know. Matthias Hirsh, who has been a professional translator since 2018, specializes in creative writing: while he enjoys working on manga, novels, and video games, he said that they have only made up approximately half of his total career thus far; advertising, journalism, and social media are other areas in which he commonly applies his abilities. “Translation is taking a document that is in one language and transferring it to another language,” said Hirsh, “while maintaining as much of the original content as is either possible or desired by the client.”

Though this might sound pretty straightforward, Hirsh also said that the process of translating and editing is a balancing act between accuracy and acceptability, “with accuracy referring to strict loyalty to the source text and acceptability referring to, basically, ease of comprehension and naturalness in the target language.” This means that not only must specific words be taken into consideration, but also subtle nuances and certain feelings expressed by original authors. “The more complex a text is,” said Hirsh, “the harder it is to maintain 100% of that source text feeling and meaning, and in some cases your client may request to make it so the target feels less (or more) foreign to the target audience compared to the original source text audience; this is localization.”

Hirsh provided a hypothetical to help illustrate his point:

Example: if I was translating a text in which the color of a traffic light when it means “go” comes up, and I was doing a 100% accuracy-informed translation, in English, I would end up saying the light is blue. But if I was doing a more acceptability-informed translation, I would say the light is green because that is the color we say the “go” light is. But it’s the same light and the same color in both cases.

Writing for Reader’s Digest, Brandon Specktor offers a more detailed explanation as to why Japanese sometimes use the word for what we tend to call blue for what we generally call green in the present day; similar difficulties arise when examining other cultures from the distant past, including ancient Greece. The point Hirsh made, of course, is that something as seemingly universal as perceiving color is subject to differing interpretations informed by cultural lenses.

When the authorial intent is immersion within a narrative, a completely accurate translation of every minute detail can prove jarring to readers or viewers who are not calibrated to a certain cultural background.

Thus, in addition to conveying an author’s meaning, translators often act as curators of the materials with which they are entrusted. This requires both intimate knowledge of original content and an appreciation of those who consume it. Kim Morrissy, who has worked as a Tokyo correspondent for Anime News Network and was the translator for screenwriter Mari Okada’s autobiography, describes translation as an act of communication. “You convey a message from one language in a way that the person listening can understand,” said Morrissy. “This means that you not only have to understand the original message thoroughly, you have to tailor the wording to suit what your audience knows.”

While expressing similar sentiments as Hirsh regarding balance, Morrissy’s experience as a journalist and her knowledge of anime subcultures have influenced an approach that differs slightly from what is usually required for fiction. Although there is never a one-size-fits-all application for every scenario, most fans of anime, manga, or anything else possess a passing familiarity with concepts presented therein:

In the context of Japanese media localization, there’s quite a lot of familiarity among fans about Japanese culture even when they aren’t fluent in the language themselves. You don’t have to hold their hands and introduce an entirely new culture to them, but they also don’t know everything. It’s a balancing act. But for me, at least, the translation process is simpler than it might otherwise be, because I don’t have to “localize” entire concepts. Bear in mind that I am speaking about this from the context of someone who worked primarily in journalism, where accuracy was always more important than the reader’s entertainment.

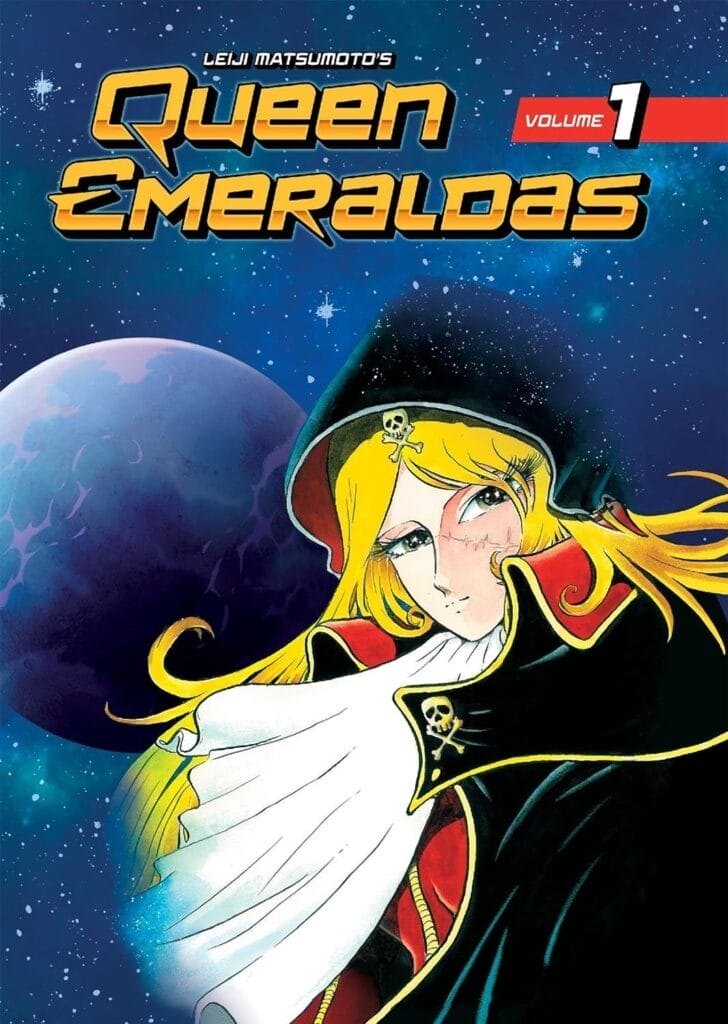

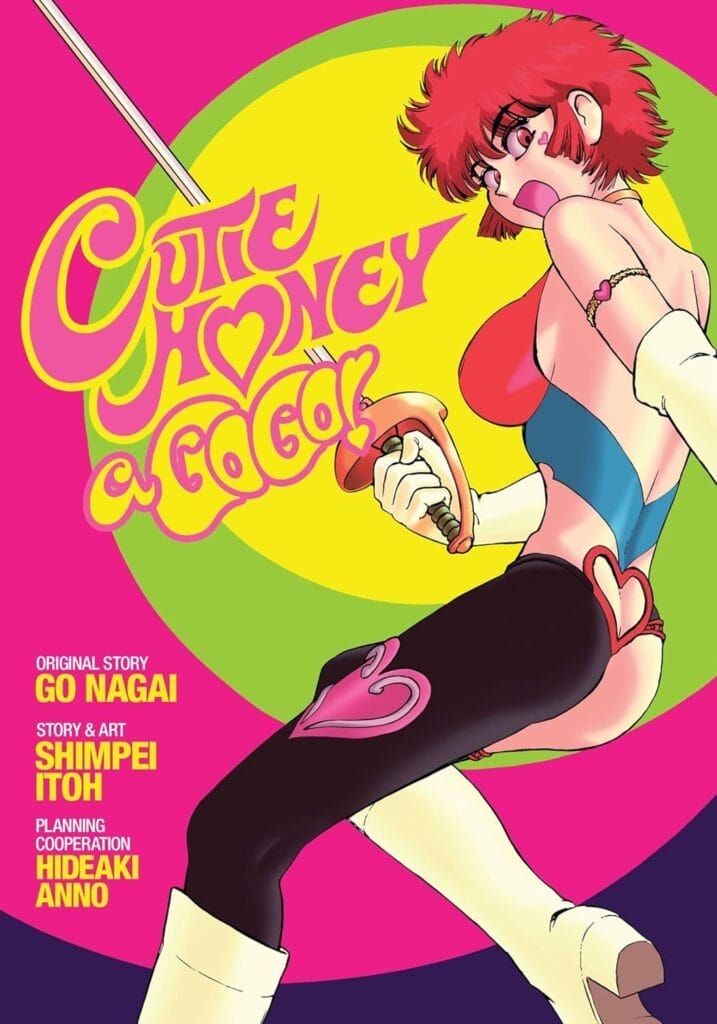

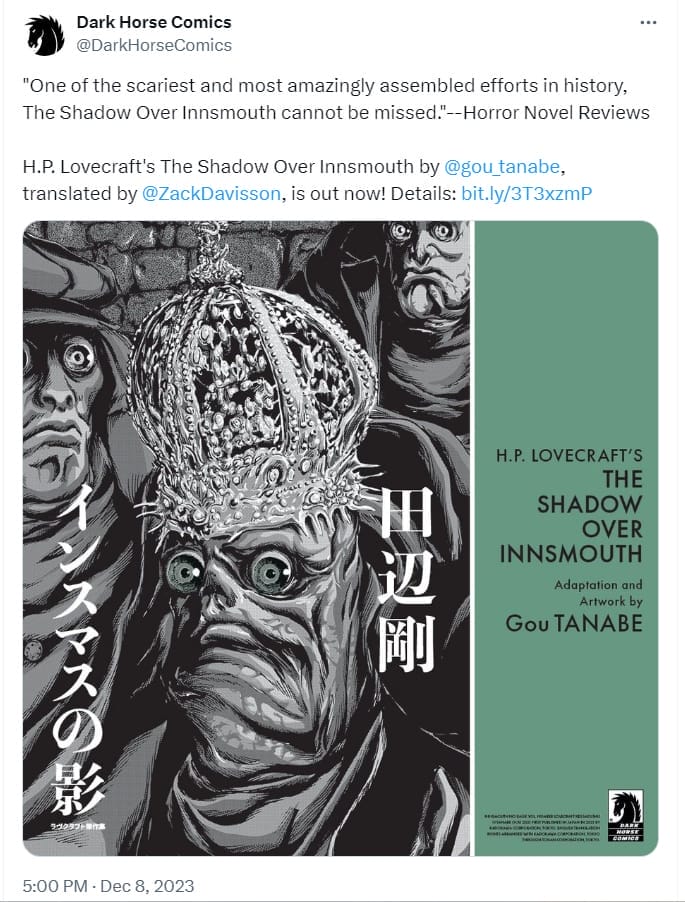

In their own ways, Hirsh and Morrissy have demonstrated that their experience has proven invaluable—and irreplaceable—to their work as translators. Zack Davisson, who has been working in the industry since 2011, can definitely speak to this fact. Having translated the work of giants like Leiji Matsumoto, Shigeru Mizuki, and Go Nagai, he has also taken up established franchises like Record of Lodoss War and even written his own books on supernatural elements of Japanese folklore. Drawing on his years of experience, he said that translating has become very intuitive for him:

I assume it is different for every translator. For me it is an intuitive process. I read the work, sort of… examine my own feelings… then try to think how to replicate those feelings in English. I often explain that I translate emotions, not words. What is important is if readers experience the same emotions as readers in the original language. If they laugh at the same beats, get surprised at the same beats, cry at the same beats… that’s what is important. If I have to use different words to do that, then I will.

While recognizing that there is no one right way to approach translation, Davisson said that there is definitely a difference between a seasoned veteran and someone inexperienced—namely, not seeing the forest for the trees. “I find that’s the difference between amateur and experienced translators,” he said. “Amateurs translate the words. Professionals translate the story.” Indeed, whereas the novice might be tempted to populate valuable real estate (be it the printed page or a screen) with copious translator’s notes about a single line or passage, a professional must find a way to balance communicating unfamiliar customs with maintaining an overall intended effect for a particular readership or viewership.

Thoughts on AI

Now that we have a grasp of what translators do, it’s time to find out what they really think of AI. Machine translators are certainly nothing new to manga and anime fandoms; writing for The Independent, Joe Sommerlad notes how Google Translate started out using rather clunky “statistical machine translation” circa 2006 before transitioning to “neural machine translation” a decade later; moreover, the foundations for such technology were built well before the 2000s. For better or worse, the 2020s promise another big technological leap. Hirsh said that his opinion is mostly the same whether talking about Google Translate or ChatGPT: at some level, it’s always about taking humans out of the equation. “I can’t speak to how ChatGPT would change the translation world, as I have never worked with it, nor do I have clear enough of an understanding of it to comfortably speculate,” he said. “I do consider machine translation to be AI, however, and I am extremely wary of it.” While Hirsh said it might be useful in a handful of fields, he does not believe that creative writing is one of them.

Morrissy understands this unease all too well. “Machine automation has come up in a lot of industries, but I think there’s a big conversation around AI because people have always thought of art as something machines could never do,” she said. “It’s like the final bastion of sorts.” But Morrissy considers herself to be rather optimistic about technology going hand in hand with societal progress in general. Rather than aiming criticism at the technology behind ChatGPT, she said that the underlying problem is how people being replaced by machines so often results in economic insecurity rather than liberation of any kind:

Personally, I think the theory around it is interesting but the way it works right now in economic terms is miserable for a lot of workers. I wish we could skip ahead to the sci-fi future where machines can do all the things and the humans don’t have to work to have access to basic human rights. The transition period is rough and I am not confident that a “post-work” economy is something that our society is even striving towards.

Davisson offered a dose of pragmatism for translators facing an uncertain future. Regardless of how one feels about it, he believes that it is an inevitability for which we all must prepare:

I would say that, like it or not, AI is coming. That genie is not going back in the bottle. And it is improving. The days of Google Translate being a joke are gone. Who knows what AI translation will be like ten years from now? Twenty? Something people need to think about. Hating it is not going to make it go away.

Technology always offers potential, but it is up to each society in its time to decide how it will be implemented. AI could be truly disastrous to the industry; then again, if used ethically, maybe it could become a comparatively benign addition or even a benefit. It behooves us to imagine a better tomorrow. For now, let’s look at how AI is affecting the translation industry in the present day.

The Capitalist Machine

As already touched upon, there is one primary—arguably the only—factor propelling the development of AI for translation purposes: money. As capitalism dictates, it is but one of innumerable money-saving measures taken by corporations to maximize profits. Translators themselves are certainly not advocating for their own replacement. “The majority of people pushing machine translation are not translators,” Hirsh said, “even if they are multilingual.”

Hirsh also pointed out that even if this compulsion to cut costs does not always result in the loss of a career, it absolutely causes a devaluation of labor by recasting a translator’s position as a supplementary role in a needlessly cumbersome process. By being assigned to rework what a machine spits out, they are forced to use their skills as translators on machine translations (MT) without being compensated accordingly:

Machine translations nearly always need to be proofread or edited by a human, so in many cases, you might as well have hired a human translator. Additionally, having to compete with AI and MT devalues our work. Rates are stagnant among translation agencies as it is. More importantly, however, MT is cutting corners and ultimately leaves the end user with a worse outcome than they would have with a qualified human translator.

Morrissy shares much of these sentiments with Hirsh. Unfortunately, those in charge of a publishing company often value cost-cutting more than quality, fair wages, or even workflow efficiency:

In practice, machine translation and AI are used as ways to devalue the work of human translators. A lot of companies are in a race to the bottom to turn the role of “translator” into “machine translation editor”, which always pays much worse. It’s tough because the tech genuinely is useful in speeding up the process, when used intelligently. But at the moment, let’s just say that the suits really overestimate the contributions of the machines when a “machine translation editor” often needs to retranslate entire sections to ensure basic quality.

Hirsh and Morrissy reveal that there are two fundamental problems to be addressed: one is the practical limitations of relying on machines to complete tasks of which they are not capable; the other is an ethical dilemma stemming from a desire to replace human beings in order to compensate them less in a world where we all have bills to pay. For the time being, AI simply cannot translate a fictional narrative or breaking news without human supervision—even though corporate entities will no doubt attempt to do so anyway. But what if the technology were truly capable? On this subject, Zack Davisson offered an anecdote:

I’ll tell you a story. I do translation battles with a friend of mine, Jay Rubin, to teach people about translation. We each translate a selected text then compare our work in front of an audience. That allows them to see what difference a translator makes to the finished text. Last time, we had a surprise third challenger—Google Translate. We put Google Translate’s version of a Murakami Haruki passage against ours. And the thing that scared us both… it wasn’t bad. It wasn’t perfect. It lacked nuance. But it was understandable.

The translation was publishable.

To some, the possibility of machines creating passable translations would be their wildest hopes come true: imagine a world where linguistic barriers are no longer an obstacle!

Misunderstandings in business and politics would vanish overnight, and we could connect with each other through the arts as never before! For others, putting faith in our current system to achieve such utopic results is far too naive. In a world where translation is a business, the primary objective is not a better world for all: it is increased profits for a few.

Hirsh leaves no room for ambiguity regarding the aggressive push for AI. In his opinion, it is to the detriment of translators, original authors, and the fans thereof. The only beneficiaries of increased automatization are those at the top:

The only reason agencies and companies want to use AI is to save money. And even if someone is hired to check (or redo) the AI’s work, that person will not be offered the same rate as if they were translating it themselves and they will not be given the time to do a thorough job. I can tell you from experience checking MT work (which I no longer do) that I never had enough time to fix everything to my standard of quality, between the time I was given and rate I was offered. They want you to work as fast as possible so long as the result is okay enough to not raise eyebrows or be incomprehensible to end users.

Mediocrity is the norm.

Morrissy also expressed her take on the current state of the industry rather candidly. She pointed out that machine translation (MTL) and AI are just a part of much larger issues like stagnant wages faced by translators trying to make a living:

At the moment, MTL and AI aren’t actively stealing jobs, but that may simply be because the demand for translated Japanese media is growing at a faster rate than it has ever been.

Perhaps one day the demand will slow and it will be harder to find work in this industry. But the years go by, and the pay rates don’t go up to match the rising cost of living. It’s not easy to make a living nowadays unless you are very fast.

Taking a step back, Davisson looked to the past in order to contextualize our present. The reality is that many of the appliances and devices surrounding us today were, at one time, the purview of a person whose labor was required to achieve the desired result:

Technology has replaced many careers across time. “Computer” used to be a profession where people did calculations all day. Now, the word refers to a machine. Many don’t realize “computer” was ever a job title. I can imagine “translator” becoming the same in the future. If AI continues to improve, I can foresee a time when “translator” is only a device in the Star Trek sense, and not a person.

There is always a cost to be paid for such advancements. As actor Spencer Tracy passionately states in Stanley Kramer’s film Inherit the Wind (1960), “progress has never been a bargain, you have to pay for it.” Heigo Kurosawa, brother of the world-renowned director Akira Kurosawa, committed suicide after his career as a benshi (a narrator for silent films) was rendered obsolete by the advent of synchronized sound in cinema. Let us hope that in any field, these transitions are made in a responsible manner to minimize the risks of such tragedies occurring when people’s livelihoods are uprooted at the behest of market forces.

The Power of The Consumer

Speaking of the market, it is always necessary to examine how consumers affect these situations. Those of us who purchase the products offered by publishers have at least some sway in these transactions. What might we do in order to preserve the integrity of our favorite franchises while getting the most bang for our buck? When discussing the potential of AI, Davisson brought up simultaneous publishing (simulpub)—which, like a simultaneous broadcast (simulcast), places an emphasis on timely releases—to highlight how the demand for quantity from consumers affects the behavior of publishers and, ultimately, the output of translation efforts:

It’s not there now. But ten years from now…? I am glad I am at the stage of my career that I am. If I were starting out as a translator now, I would not feel confident of the longevity of my career path. Especially as consumers have proved that they care more about speed than quality, especially in manga. Getting great translations doing simulpub, for instance, is incredibly difficult. But readers are willing to sacrifice quality for quantity. And that’s totally fine. Perfect should never be the enemy of good. Sometimes good and fast is better than great but wait.

Those of us who buy manga, light novels, or anything else originally written in a language we cannot understand must bear some responsibility for the quality we ultimately receive. But is the future of the translation industry as it relates to anime and manga in the hands of consumers? Hirsh certainly believes so. If we do not favor AI replacing flesh and blood, then we must send a message to companies making these kinds of decisions:

There should absolutely be pressure on companies that make creative work to not use AI or MT. And in the case that consumers know that a company used either for a work, they should boycott that work. They should know they are not being given the best possible outcome, they are being handed the most affordable and fastest. This is not about quality or accuracy, this is about saving money. Please read, watch, and play officially licensed manga, anime, and games. Please do not believe companies or publishers when they tell you that machine translation or AI are beneficial to anyone but themselves.

Morrissy stressed awareness over a direct call to action on the part of consumers. Recognizing the eternal struggle between management and workers, she said that those in the translation industry must always stand up for themselves to protect their interests. Within our current socioeconomic and sociopolitical framework, self-preservation is a must:

Corporations should definitely be more aware of the current limitations of MTL/AI and not see them as a shortcut to reducing labour costs. It’s not just purely a matter of ethics but making people aware that current applications will either see a big drop in quality or require more human labour than they were led to believe. As for the consumers, I don’t necessarily think they should be expected to vote with their wallets purely over this issue, and it would be naive to expect them to do so, honestly. In the future, as AI improves, we may see the debate take on new forms. Personally, I like being optimistic about technological progress. I welcome the tech, just not the way business culture works around it. People have to argue for their rights as workers, otherwise those rights will get eroded over time. That’s just unfortunately how the world works.

According to Davisson, there is no panacea for these topical issues; there are no cure-alls that can make these very real problems disappear. In his opinion, the interplay between producers and consumers will determine how things shake out:

I don’t have any easy answers. Manga IS capitalism. Translation is a job. Those that learn to adapt to technology will still have jobs in the future, those that don’t… won’t. I hope companies put anti-AI controls in their systems. I recently had to sign a No AI clause in a contract, and I appreciated that. But that will also have to be consumer-driven. Do readers want fast and good or great and wait? That will ultimately drive everything.

But Davisson did offer some speculative ideas to thwart the seemingly inevitable devaluation of translators and their work. If translators themselves are viewed in a similar vein as authors and artists, as the directors and designers who help bring memorable stories and unforgettable characters to life, perhaps their erasure could be stalled if not outright prevented altogether. In the end, it comes down to what the consumer wants:

I think something companies could do is push good translation to the forefront, make it a selling point. They’ve spent decades vanishing translators from the industry, taking their names off the covers of books, then moving them to the fine print. But if they did the reverse, educating readers and marketing quality translations over speed…. it’s possible. But again, that will be 99% consumer driven. How people choose to spend their dollars is the greatest power they have and determines everything about how the manga industry will look in the future.

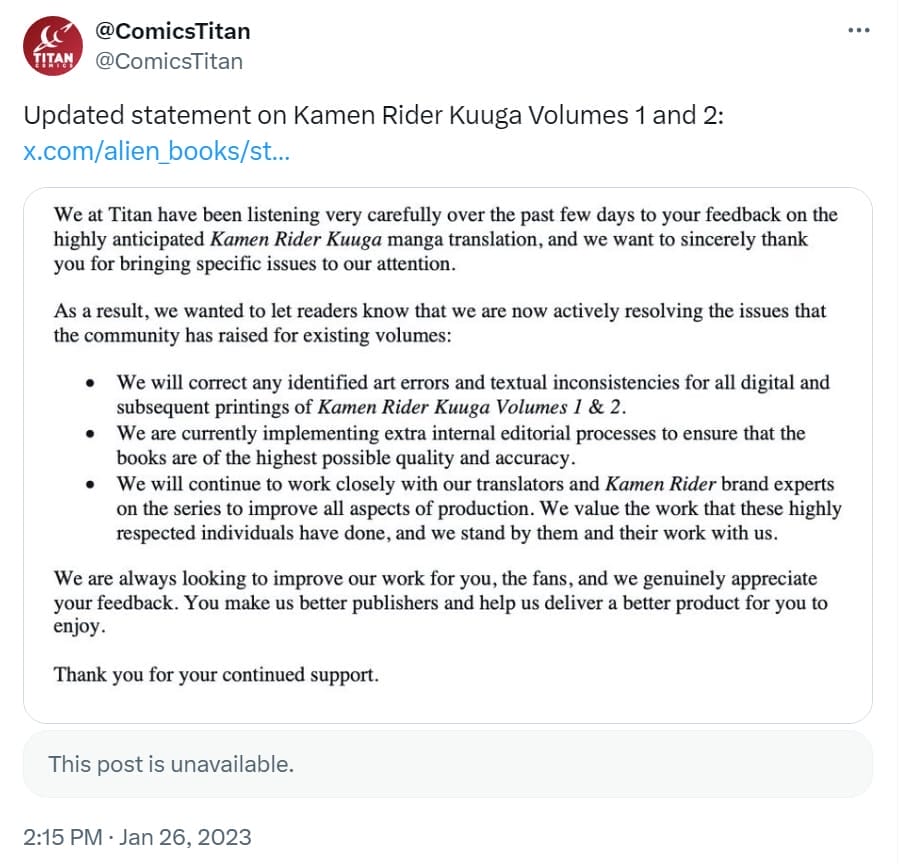

One of Davisson’s inspirations, Lafcadio Hearn, is a perfect example: a naturalized citizen of Japan who died over a century ago, his translations of Japanese folklore remain a selling point for publishers to this day. There are certain advantages to advertising good translations—for starters, it might help cancel out bad ones! Writing for CBR, Hilary Leung chronicles a translation debacle involving the Kamen Rider Kuuga manga. After Kaylyn Saucedo and others voiced their suspicions that machine translations were being used in an official capacity, the publisher, Titan Comics, released a statement: therein, they claimed that early drafts were done hastily for “marketing purposes” whereas the printed books were translated by “highly respected translators” in the business.

Time will tell if those involved in marketing other properties will adopt Davisson’s suggestion to prevent this type of faux pas. In the meantime, it is incumbent upon those working in the industry to support themselves and each other: accepting less than your peers might land you a job today while costing you a fulfilling career tomorrow. As far as the industry side of this equation goes, there are steps to be taken by both translators and those who wish to benefit from their abilities to ensure a robust ecosystem of exchange.

Conclusion

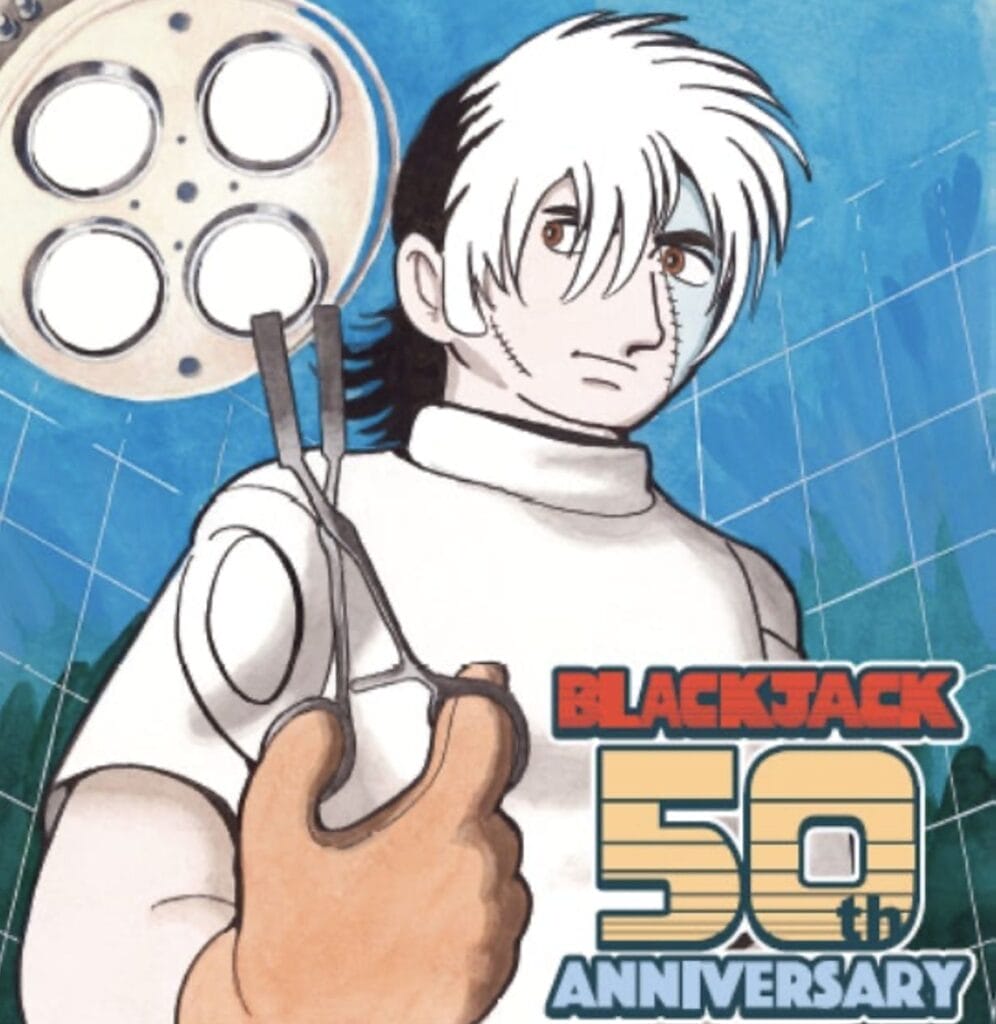

At present, AI has already made waves in our culture at the intersections of commerce and art, of politics and economics. In June of 2023, NHK World-Japan announced that an AI project would attempt to “continue” Osamu Tezuka’s Black Jack manga. A revered figure in the histories of both manga and anime, Tezuka himself has been dead for over thirty years; even though the project is being overseen by his son, it has already provoked strong reactions across the globe. The ripples caused by AI will not be confined to professional spheres: one way or another, fans will have to deal with it. As Jie Yee Ong reports for The Chainsaw, the wiki-hosting service Fandom has been accused of using AI to populate its vast trove of user-generated content with erroneous information. Numerous news sites (another way through which fans remain informed) are also susceptible to this top-down treatment.

For The Verge, Mia Sato reports that G/O Media, owner of Gizmodo and The A.V. Club, is already using bots to write listicles; as Sato puts it, “embarrassing mistakes” concerning basic Star Wars chronology were made almost immediately. Self-described nerds, geeks, and otaku will have to decide for themselves if search results populated by vagrant falsities are something they’re willing to tolerate.

For the patrons of various entertainment franchises, how they spend their money is ultimately their choice. Ethical consumption has long been a topic of debate for anime and manga fans in one form or another; AI is poised to become the latest iteration of this ongoing conversation. If human translators being replaced perturbs you, then speak your mind! Let companies know that you will not passively accept such standards. Conversely, if the prospect of translators going the way of soulless computers does not bother you, ask yourself why that might be the case. After all, you probably wouldn’t want your favorite creator to be replaced by software! Stories told by the likes of Akira Toriyama, Yoshihiro Togashi, and Eiichiro Oda endure because they resonate with other people—and unless you’re fluent in Japanese, you have translators to thank for making their work accessible. But would you regularly purchase manga drawn without human input? How enthusiastically would you keep up with an anime series written by an algorithm featuring characters voiced by AI without any human direction? Plenty of CEOs wouldn’t think twice of doing away with any part of the production process as long as it saved them money. If paying customers want human creativity to flourish, then they must be willing to cultivate it; otherwise, we risk losing tomorrow’s generational talent. Think of what the industry would look like without Rumiko Takahashi or Naoko Takeuchi. Imagine a world without the published works of Kentaro Miura or Kazuki Takahashi, who now live on through their indelible creations. How much are we willing to sacrifice in the name of convenience?

Where we draw the line is up to us. Wherever consumers lead, moneyed interests will follow.

For everyone’s sake, we should all endeavor to pave the road on which we currently tread with more than just good intentions.

Works Cited

- “AI manga project aims to continue Astro Boy creator’s work.” NHK World-Japan, 13 June 2023, https://www3.nhk.or.jp/nhkworld/en/news/backstories/2521/. Accessed 1 Sept. 2023.

- “The AI-Powered Manga Translation Service Sharing Beloved Titles with the World.” Kizuna, 20 Feb. 2023, https://www.japan.go.jp/kizuna/2023/02/manga_translation_service.html. Accessed 1 Sept. 2023.

- Deck, Andrew. “AI translation is jeopardizing Afghan asylum claims.” Rest of World, 19 Apr. 2023, https://restofworld.org/2023/ai-translation-errors-afghan-refugees-asylum/. Accessed 27 Aug. 2023.

- Inherit the Wind. Directed by Stanley Kramer, performances by Spencer Tracy and Fredric March, United Artists, 1960.

- Lazzaro, Sage. “Generative A.I.’s hallucination problem has companies contemplating if they want to ‘move fast and break things’ yet again.” Fortune, 8 Aug. 2023, https://fortune.com/2023/08/08/generative-ai-hallucination-problems-will-companies-mo ve-fast-and-break-things-again/. Accessed 27 Aug. 2023.

- “Learning to lie: AI tools adept at creating disinformation.” AP News, 24 Jan. 2023, https://apnews.com/article/technology-science-business-artificial-intelligence-afb4618ff5 93db9e3e51ecbd91dc3eef. Accessed 31 Aug. 2023.

- Leung, Hilary. “Kamen Rider Kuuga Manga Appears Machine Translated Due to Inaccuracies.” CBR, 25 Jan. 2023, https://www.cbr.com/kamen-rider-kuuga-manga-mistranslated-marketing-pages/. Accessed 1 Sept. 2023.

- Mangan, Dan. “Judge sanctions lawyers for brief written by A.I. with fake citations.” CNBC, 22 June 2023, https://www.cnbc.com/2023/06/22/judge-sanctions-lawyers-whose-ai-written-filing-conta ined-fake-citations.html. Accessed 27 Aug. 2023.

- Ong, Jin Yee. “FANDOM Wiki Criticised For AI-Generated Answers Riddled With Mistakes.” The Chainsaw, 21 Aug. 2023, https://thechainsaw.com/nft/fandom-wiki-ai-generated-answers-chatgpt-hollow-knight/. Accessed 1 Sept. 2023.

- “Open AI Charter.” OpenAI, https://openai.com/charter. Accessed 27 Aug. 2023.

- “Sarah Silverman and novelists sue ChatGPT-maker OpenAI for ingesting their books.” AP News, 12 July 2023, https://apnews.com/article/sarah-silverman-suing-chatgpt-openai-ai-8927025139a8151e26053249d1aeec20. Accessed 1 Sept. 2023.

- Sato, Mia. “G/O Media’s AI ‘innovation’ is off to a rocky start.” The Verge, 6 July 2023, https://www.theverge.com/2023/7/6/23785645/go-media-ai-generated-articles-gizmodo-a v-club-artificial-intelligence-bots. Accessed 1 Sept. 2023.

- Sommerlad, Joe. “Google Translate: How does the multilingual interpreter actually work?” The Independent, 24 Mar. 2017, https://www.independent.co.uk/tech/how-does-google-translate-work-b1821775.html. Accessed 27 Aug. 2023.

- Specktor, Brandon. “This Is Why Japan Has Blue Traffic Lights Instead of Green.” Reader’s Digest, 31 Jan. 2023, https://www.rd.com/article/heres-japan-blue-traffic-lights/. Accessed 27 Aug. 2023.