Table of contents

With the advent of streaming services, we are currently living through an era of unprecedented access to anime. Some shows are simultaneously released online with subtitles, and even a select number with English dubs, as they air in Japan.

Despite this, there are still those participating in the good old-fashioned piracy that helped create the anime fandom as it is today in North America, doing so surprisingly enough in some of the exact same ways they were over forty years ago. So why was this kind of piracy done in the first place, why was it necessary, and why is a dedicated group of anime fans doing work to preserve it with anime more easy to access than ever before?

Early Anime Fandom

Our story begins when anime first appeared in North America In 1961, with Magic Boy and The Tale of the White Serpent opening as the first and second anime films in the United States. Two years later, in 1963, Astro Boy debuted on American TV, paving the way for Gigantor (Tetsujin 28-go) and Kimba the White Lion. All three shows would become major television hits and, while they were technically anime, they didn’t register as anything different from the other shows airing on Saturday mornings at the time. According to anime historian Fred Patten, they were “considered by the kids who watched them as just more TV cartoons.”1

Things started to change in 1975, when Sony’s Betamax combination LV-1901 TV/VCR floor model debuted in stores as the first consumer VCR. This was quickly followed three months later by the first standalone player, Sony’s Betamax SL-7200.2 Prior to this point, video tape recorders could cost $50,000, $538,188 in today’s money, with a 90-minute tape to record on costing $300, around $3,229 today. This left viewers with few options and at the whims of studios re-releasing things in theaters or on TV. These new VCRs heralded an era of on demand entertainment for the first time by allowing people to record and share television programs on their own schedule due to their affordability and convenience.

“Back then, if you wanted to screen science fiction films, you had to rent 16MM films from places,” Mark Merlino, Co-founder of the Cartoon/Fantasy Organization and founding member of the then-nascent furry fandom recalled. His early experiences at sci-fi conventions like Loscon not only lead to him screening films himself, but meeting Wendell Washer, a storyboard artist for Filmation at the time.

“[Wendell] was recording animation off TV, including shows from Japan that were broadcast on UHF stations in Southern California on Japanese local networks. The shows were recent productions from Japan, 16 MM film that had burned-in subtitles produced by Kiku TV in Hawaii.” Armed with several of Wendell’s tapes as well as some of his own, Merlino set up a TV at Loscon in a meeting room and started showing tapes, including episodes of Yuusha Raideen and Getta Robo G to a modest group of “about 20 people.”

The Role of Anime Clubs

Among those present was Fred Patten, who suggested a monthly informal screening of these sci-fi focused shows at the Los Angeles Science Fiction Society (LASFS) clubhouse each month. “Merlino started to record s-f programs off of TV and bring them on his V-Cord to LASFS meetings and s-f parties,” Patten said. “A small subgroup developed within the LASFS who encouraged Merlino to emphasize the giant-robot cartoons and forget the other stuff. It was my suggestion to turn the irregular giant-robot cartoon screenings into a separate club with regular, publicized meetings.”

That “small sub group” would eventually become the Cartoon Fantasy Organization (C/FO), one of the oldest organizations for animated fandom with a particular focus on Japanese animation. While those small number of subtitled films recorded off TV remained popular, a number of intrepid fans with connections in Japan began trading episodes of American TV for anime, in an attempt to try and watch more of the shows they were enamored with even without translations.3 As media scholar Henry Jenkins noted in an interview, “We didn’t know what the hell they were saying, but it looked really cool.”

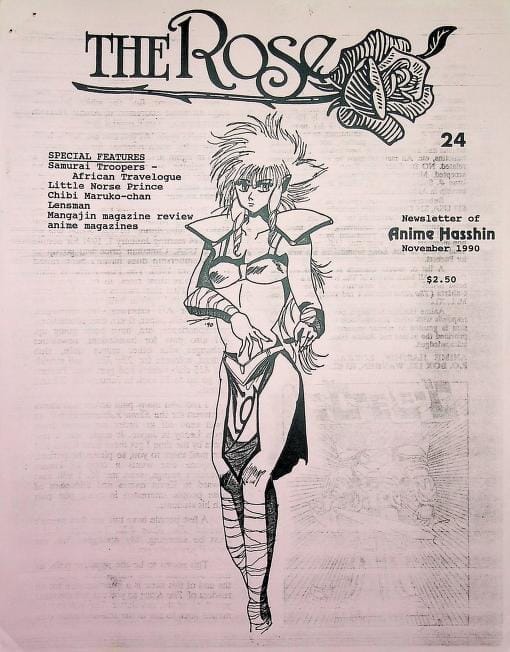

Burgeoning clubs like C/FO and Anime Hasshin! took efforts to make these recorded shows and films more readily available for fans while expanding their own collections. One of those efforts would become the most immeasurably valuable resource to the anime-obsessed in the 1980s — tape trading lists.

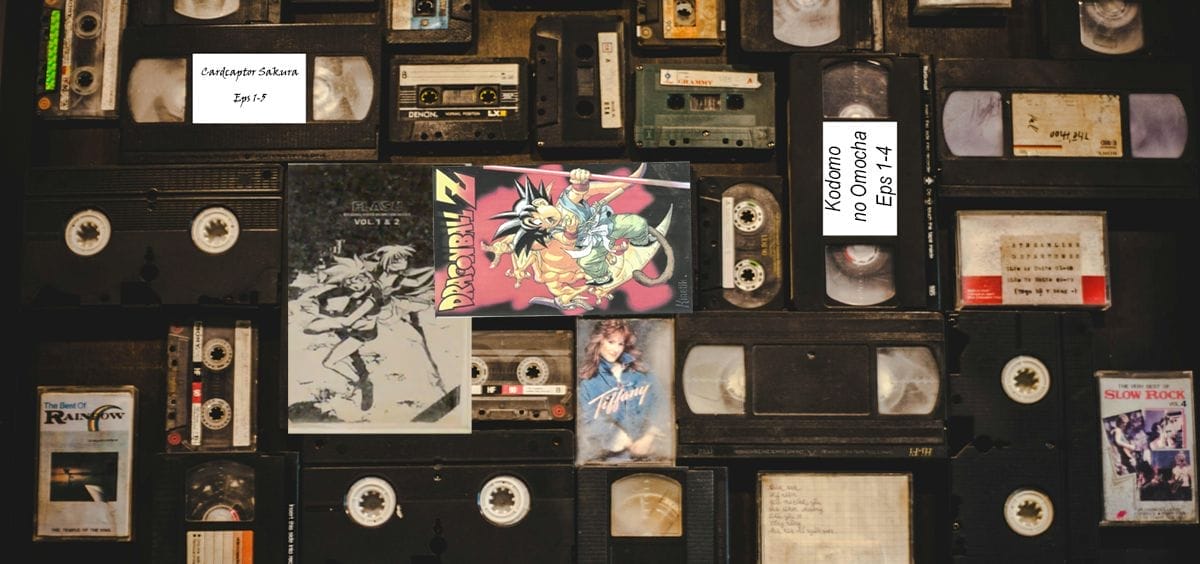

“An important part of Anime Hasshin was its Tape Traders List,” Lorraine Savage, founder of the fan club explained. “The club maintained a list of volunteers who were willing to copy anime from their collection for other Anime Hasshin members.” Collectors would have to send letters, blank tapes, and sometimes cold hard cash to get the shows and movies they wanted to see. As William Chow, founder of the fansubbing group Arctic Animation recalled, “Back in the day, if you wanted to get anime and you wanted […] to get your sources for anime, you actually had to do some […] real writing and a lot of writing.”

This was before two-day shipping was a twinkle in Jeff Bezos’ eye, so it would often involve waiting for weeks, or even months, unsure if or when the tapes would arrive. Some of these tapes would be copies of copies, or recorded at a lower quality so more episodes could fit on each tape. Because of this, first or second-generation copies —tapes that were only copied once or twice from the original—were highly sought after for their higher quality due to less overall degradation.

The First Anime Fansub

It was one thing to get these tapes but a whole ‘nother thing to understand what was on the screen. For untranslated shows, some fans printouts with basic information on the characters or episode recaps to help others follow along. Viewers Guide to Japanese Animation, distributed by Books Nippon, was one such resource. “It was originally the program guide for a Japanese animation festival at Baycon ’86,” said Tom Warburton, creator of the hit series Codename: Kids Next Door explained in a blog post. “But this edition was distributed by Books Nippan as a primer for people like me that needed to know what the hell was going on in their bootleg anime VHS tapes.” On page forty-eight of that book was a mention of the first fan-subtitled anime ever created.

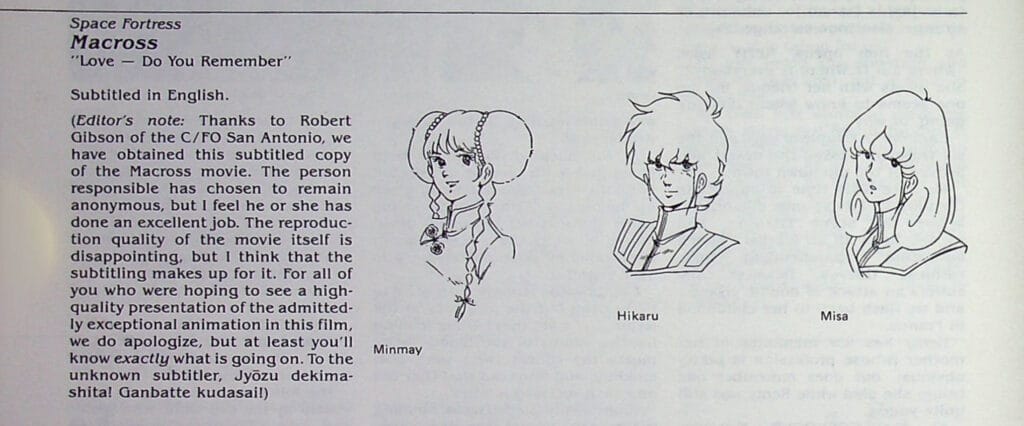

“I was completely blown away by that movie,” said David Riddick, co-founder of US Rendition, which helped pioneer home video distribution of anime in North America.4 ”As a fan project, my friends Mario and Glen Ho and I did a movie translation script of Macross: Do You Remember Love?” Robert Napton, the other co-founder of US Rendition, also talked about the project. “[I]t was called the ‘Macross Movie Gold Script.’ This was a fan publication, but it was a line for line translation of the movie.” The C/FO chapter of San Antonio would eventually use more pieces of affordable and accessible technology coming to the market at the time to add that translation to a VHS tape. Thus the first “fansub” was made.

Fansubbing Expands

This trend known as “fansubbing” led to tape trading becoming more popular than ever, as fans could easily enjoy these works translated for the first time.5 Some of these fansubbing groups, like Arctic Animation, TechnoGirls, and Kodocha Anime would become the biggest distributors of fanmade tapes with personal collectors moving more to the sidelines but never truly being forgotten.

Eventually, personal websites containing trading lists and email gaining popularity would help avoid some of the hilarious to annoying misadventures that were a part of the anime fandom of that time. Despite easier access to trading, fansubs became less popular as reputable fansubbers dropped projects that were officially licensed for import to North America and more companies stepped up to do so in the early 1990s.

Broadband internet would continue to grow in popularity and with it, a perfect storm to revive fansubbing’s popularity was formed. New video compression standards would form, with MPEG-1 releasing in 1991. Just like the VCR revolution in the days of old, the first Digital Video Recorder hitting the market in 1999 made it easier to record anime as it aired. Peer-to-peer file-sharing clients like LimeWire, and Kazaa hit the scene in 2000 and 2001 respectively, making it possible to get these new high-quality videos into fans’ hands fast. The higher quality available and speed to access shows made space for fansubbed projects to come into vogue once more as shows could once more be translated before being officially licensed. IRC chats which had been used to organize fansubbing efforts also became a place to distribute these files thanks to these new, easier to trade formats as well.

The internet would continue to advance in use and popularity until YouTube hit the scene on February 14th, 2005. Now there was little need to send VHS tapes to each other when videos like “Revolutionary Girl Utena Episode 6 [Part 1 of 5].mov” were available to be passed around to a new generation of anime fans and those who were less internet savvy.

Tape Trading Today

With A History of Violence being the last major studio release on VHS back in 2006, it would be reasonable to think that, outside of nostalgia, the format would be abandoned. On the contrary, the ongoing demand for players capable of playing video cassettes resulted in a VHS/Blu-ray combo player hitting stores in 2009. Furthermore, VHS player parts were still produced until 2016.

During this time, interest in fansubbed anime VHS never fully waned. Between 2010 and 2014, Glen Pearce of fansubs.ca recorded orders for forty-two tapes, many more than for the DVDs that were also on offer. In fact, they were still open to distributing tapes until January 5th, 2022 when equipment failure and other factors forced Pearce to change focus.

“My experience over the last few years is people periodically asking about tapes then I never hear from them again or them asking if I can do it cheaper,” He explained in an update. “This leads me to believe most people asking simply can’t afford tapes and postage, never mind the cost of maintaining a pool of antique VCRs.” With the process having “no hope of being self financing like it used to be,” combined with the increased cost of keeping old equipment functioning, Pearce, like many others, shifted his focus toward digitizing and preserving these fansubs instead of producing new tapes.

One of those projects is Senshi Fansubs which, with the help of fansubs.ca, was able to digitize over 200 fansubbed Sailor Moon episodes and movies, which are now available on The Internet Archive. Fansubs.ca also maintains an archive of the custom cases and labels many of these fansubbing projects used for their videos, so modern-day collectors can print them themselves. This allows new fans to have a truly authentic collection, while also preserving a vanishing part of anime fandom history.

Senshi Fansubs also maintains a trade list and isn’t the only modern website to have one. A small group of netizens have taken to Neocities to host their own lists on brand new sites. One such person is DisasterBeast, creator of the VHS FanSubs subreddit and a Discord group dedicated to VHS fansubs. DisasterBeast hopes to create a “new tape trading ring” and maintains a list of traders. The Oldtaku Fansub Archive Project, which is dedicated to preserving fansub tapes, is among those on that list.

“We’re familiar with fanfiction and fanart, but the production of fansubs required enormous amounts of effort for very little tradeoff,” Natalie, who operates the project explained on their about page. “There was no kudos system or comment gallery to show them support. Groups like Techno Girls, Soyokaze, and Kodocha Anime spent thankless hours creating content that shaped an entire generation of anime fans. This is why I’ve decided to start a fansub archive project.”

Even with the ease of subbed anime available via streaming services, fansubbing has not died either. Some projects focus on adding subtitles to older shows unlikely to ever see an official release. Due to many complaints about the quality of subtitles on Netflix, especially with the recently popular Komi Can’t Communicate, viewers have turned to fansubbers to get better experiences. Even a number of the old fansub groups are also still alive and kicking, with the last member of Techno Girls working on redoing the fansub for Dear Brother according to a recent update.

It is also impossible to deny that almost all streaming services are currently estimated to be losing money meaning it’s not impossible to see a collapse of our current economy of anime convenience in the future. If this were to happen, fansubs would skyrocket in popularity once more. With the returned popularity of VHS, perhaps there would even be a renaissance of tape trading, be it for archival or just for modern fans with anemoia who want to experience a taste of early anime fandom for themselves.

No matter what the future holds, it is obvious that anime fans are an industrious bunch who have a history of doing whatever it takes to access the media they love and preserving some of our oldest traditions. With the practice of VHS trading managing to survive over forty years until now, who knows how fans will be watching their favorite shows another forty years in the future.

- Patten, “This Month in Anime History: March 1976—The First Giant Robot Anime, Brave Raideen, Comes to American Television”, 54 ↩︎

- Patten, “This Month InAnime History: November 1975 – The First Consumer-Marketed VCRs Go On Sale In The US”, 54 ↩︎

- Patten, “This Month in Anime History: March 1976—The First Giant Robot Anime, Brave Raideen, Comes to American Television”, 54 ↩︎

- “A Brief History of the Cartoon/Fantasy Organization, America’s First Anime Fan Club — by Sy Sable”, 2020 ↩︎

- Ed Gomez, “The US Renditions Story An Interview With The Founders” Genki Life #9, 25 ↩︎