Table of contents

The Avengers changed the game for cinema in 2012. It was around this time I debated whether or not I’d dive into the source material that inspired this movie and many others like it. Unfortunately, as a teen girl, I felt comics were not made for me. Between an unwelcoming comic shop, oversexualized depictions of women, and judgemental comments from male classmates, I gave up on that interest until college.

Instead, I focused on a medium that was more welcoming for girls – shojo manga and anime. Where comic publishers and my local comic community failed, shojo series like Sailor Moon, Ouran High School Host Club, and Alice in the Country of Hearts welcomed me. This is unsurprising when one looks at the definition of shojo. As the New York Public Library points out, shojo series primarily target teen girls; meanwhile, shonen series target teen boys.

American comics, on the other hand, are not as upfront about gendered marketing. While there are age ratings, it’s often on the readers to assume whether or not a comic is made with women in mind. It’s not a surprise then that a younger me assumed comics – specifically Marvel and DC – were not made for readers like me when men dominated the industry, male characters were the main protagonists, and the few leading women I saw at the time felt like objects.

Thankfully, I moved past this assumption when I entered college. Independent titles like Kelly Sue DeConnick and Emma Rios’ Pretty Deadly and Joelle Jones’ Lady Killer inspired me to pursue a career in comics. I’ve worked in comic shops since 2019, have been a comic critic, interviewed industry professionals, and have written my own published comic, “Negative Realm.” Fully immersed in this industry since my first internship in 2017, I’ve seen how much has changed since 2012. I’ve also seen how this industry can benefit from following in the footsteps of shojo series.

How Do Shojo Series Succeed Where American Comics Fail?

As mentioned earlier, shojo series target a teen girl demographic, while josei series target female readers 18 and older. Yes, these are demographics, but there are expectations of shojo and josei series beyond what their intended audiences are, similar to how there are expectations for genres.

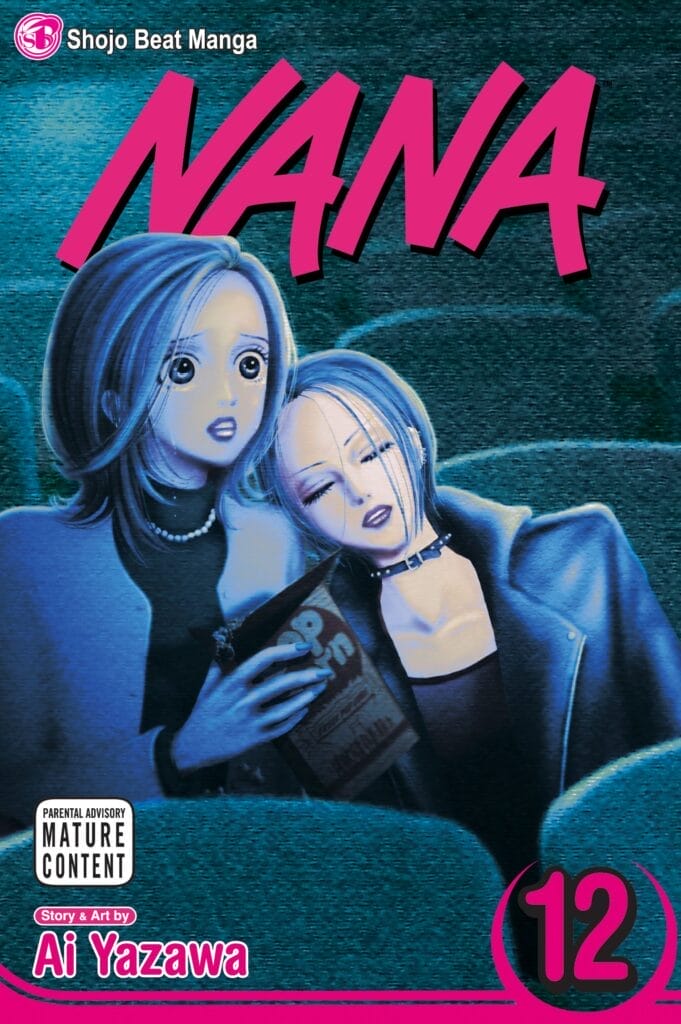

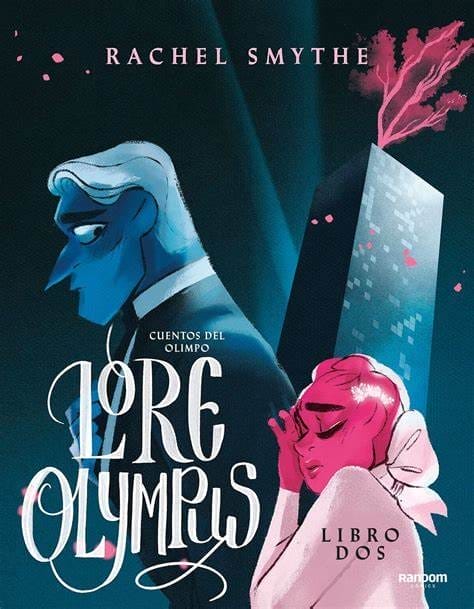

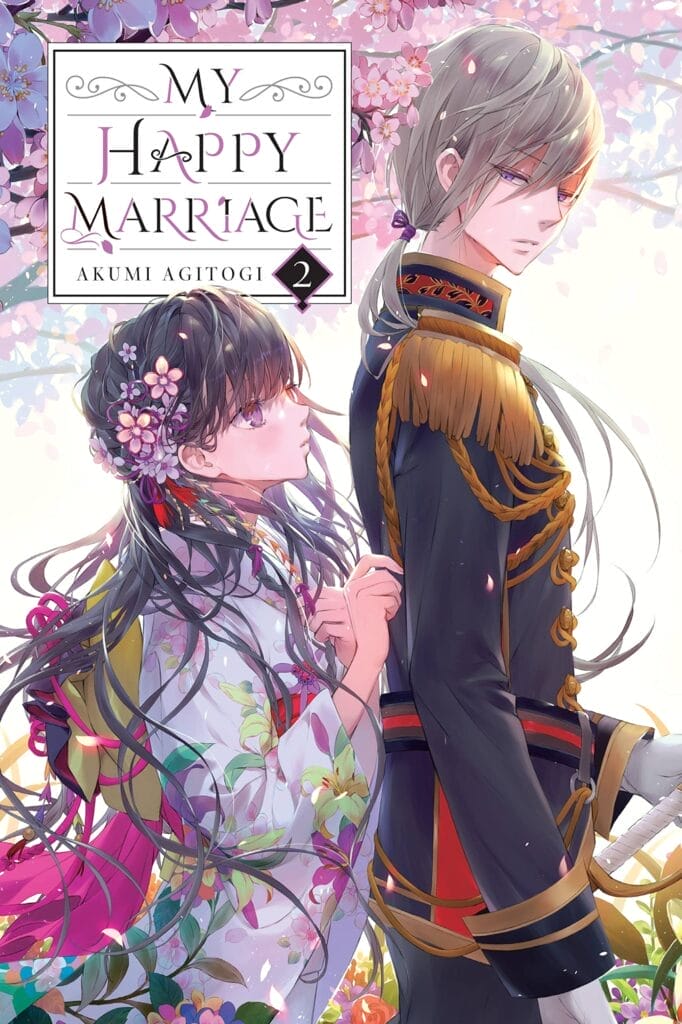

The New York Public Library claims shojo and josei series often feature romance, with the former dealing with coming-of-age themes while the latter handles more mature themes. Along with that, certain styles are associated with these demographics. To compliment the romantic and dramatic themes in shojo and josei, for instance, a lot of art has a feminine, romantic quality to it, as seen in the floral imagery of Fruits Basket and My Happy Marriage, as well as the fashion focus in Nana and Paradise Kiss.

These visuals, as well as themes, help convey that series under these demographics are geared toward women. That is not to say women inherently have to enjoy these series, relate to the subject matter, or like the more feminine aesthetics. However, it is a way to remind potential readers these are stories with women in mind, as well as remind them that manga is more than shonen series.

American comics, on the other hand, struggle with this, as the public perception continues to be dominated by one genre – the superhero genre. When it comes to pulling books for regulars at my local comic shop, Marvel and DC dominate pull lists every week. In fact, according to Statista, 62 percent of comic shop sales are from Marvel and DC. Along with that, Marvel and DC have a more well-known brand than other comic publishers thanks to the countless movies, shows, and video games that have come out over the decades.

This lack of genre diversity on a mainstream level can deter potential readers who are not interested in superhero comics. Manga, on the other hand, caters to a wider audience thanks to a variety of genres. Looking at the shojo demographic specifically, there are slice-of-life stories (Ouran High School Host Club), as well as historical dramas (The Rose of Versaille), supernatural romances (Fruits Basket), and even superhero tales (Sailor Moon). For women entering the world of comics, manga has more genres to pick from on the surface, including superhero stories. Furthermore, superhero books under the shojo umbrella may appear to be more welcoming to women than American periodicals – single-issue comics.

Of course, women can enjoy American superheroes. I have met many female fans working at my local comic shop, and there are incredible women comic creators on popular titles today, like Catwoman, Poison Ivy, Harley Quinn, Power Girl, and Ms. Marvel. Despite this, the public image of comics – specifically superhero periodicals – is still masculine.

While I am a superhero comic fan today, it was this genre of comics that kept me from pursuing the medium until college. That had a lot to do with how women were depicted in the periodicals back then. At the time, I didn’t see a lot of women in leading roles, and the ones I did see felt like eye candy. Even heroes I adored, like Starfire, could not rope me in when all I saw were women wearing next to nothing with body proportions that did not help my teenage insecurities. It’s no wonder, then, that I would turn to the likes of Sailor Moon for my hero fix.

Since high school, things have improved in terms of on-page representation, as evidenced by the popularity of female characters like Harley Quinn and Ms. Marvel; however, male heroes are primarily leading periodicals. Based on the previews for February 2024, only 21 percent of the solo titles for Marvel are about women. On the DC front, its three most popular characters – Batman, Superman, and Wonder Woman – are not treated equally number-wise. In December 2023, Batman had seven solo series, and Superman had four. Wonder Woman, on the other hand, had one.

With one genre dominating the American comic industry, and said genre leaning toward one demographic – men – the American comic industry can come off as unwelcoming to new readers, specifically women. As addressed earlier, there are female fans, ones who enjoy books marketed toward women, as well as comics marketed toward men. However, how successful the American comic industry is at welcoming this demographic is debatable, especially when compared to how manga welcomes the female demographic through shojo series, as well as series outside the shojo demographic.

Similar to how women do not have to enjoy shojo series, they can also be fans of shonen series, despite not being part of the technical demographic. In fact, there is often an active female fanbase for shonen series, as seen on social media with the likes My Hero Academia and Demon Slayer. As for myself, while shojo series like Sailor Moon and Alice in the Country of Hearts were my introduction to manga, I now read shonen series like One Piece, Spy x Family, and Witch Hat Atelier, on top of josei series like Wotakoi: Love is Hard for an Otaku.

Along with that, there is no denying the influence shojo has on shonen. Spy x Family is one of the most popular shonen series today (via ComicBook); however, the slice-of-life elements, marriage of convenience plot line, and themes about found family can suit a shojo series too. These elements are not exclusive to shojo series, as there are numerous shonen series that explore elements like this. However, where shonen series – specifically battle shonen – are often associated with action-driven plots, shojo series, according to the New York Public Library, are associated with emotion-driven plots. Spy x Family delivers on both fronts, thus appealing to shojo and shonen demographics at the same time, something American superhero comics struggle to do.

Along with that, the creator of Spy x Family, Tatsuya Endo, pulls direct inspiration from shojo series like Boys Over Flowers by Yoko Kamio when it comes to designing characters like Damian Desmond, according to the official Spy x Family fanbook. One can also see how shojo series inspire shonen series like Spy x Family beyond character designs and plot elements.

Looking back at Damian, when Anya apologizes to him, his perspective of her changes. Her “cute factor” is enhanced to communicate to readers how Damian is developing a crush on her. Along with that, the background takes on floral elements to emphasize Damian’s feelings toward Anya. This type of visual storytelling is prominent in romance-driven shojo series, and it’s unsurprising that this is how Endo approaches Damian’s emotions when the character is inspired by a pre-existing shojo character.

Turning toward another manga that blurs the line between shonen and shojo is Witch Hat Atelier. Like Spy x Family, Witch Hat Atelier is technically classified as a shonen series; however, stylistically, it feels akin to a fantastical shojo set in the past, like The Rose of Versailles, thanks to its baroque yet whimsical world, adorable leading women, and bishonen-esque mentor figure. Also like Spy x Family, Witch Hat Atelier is reminiscent of shojo series beyond the stylistic elements.

As Kotaku points out, shonen series often feature male characters in leading roles given the target demographic; however, that’s changed over the years. This is seen in Witch Hat Atelier, which not only has a female lead, but the supporting cast is predominantly women. Other shonen series, like Chainsaw Man, feature many women in leading roles. Featuring women in such prominent roles is normal for shojo series, as Kotaku addresses, but modern shonen series like Chainsaw Man, Spy x Family, and Witch Hat Atelier are willing to feature women in these roles too.

Who the leading characters are in a series is one way to tell readers who the target demographic of said series is. Therefore, seeing women featured in a series lets new female readers know there is a place for them in this fandom, which is what shojo and josei series have done for decades.

Going back to my introduction to manga, I was drawn to shojo series because they featured complex women in leading roles, something that was not prominent in the superhero comics available to me at the time. If those American comics featured women like Sailor Moon or Haruhi Fujioka up front, I may have reconsidered putting comics on hold.

Shonen series are also welcoming more readers who traditionally are part of the shojo demographic by putting multiple female characters in key roles. There is no Spy x Family without Yor or Anya, there is no Chainsaw Man without Makima or Power, and there is no Witch Hat Atelier without Coco or her fellow witches in training.

Manga has taken note of how important the shojo demographic can be for the medium at large. American comics, on the other hand, struggle. More specifically, superhero periodicals – the face of the industry – struggle. Meanwhile, “independent” comics are taking note of the success of manga, as well as the storytelling tactics used in shojo series.

Independent Comics and Webtoons Understand the Value of Shojo Fans

Independent comics – a term colloquially used in comic shops for books outside of Marvel and DC – embrace the romance genre more than superhero comics do. This is partially due to the Comics Code Authority (CCA).

In 1954, the CCA issued a moral mandate on American comics. According to the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund’s She Changed Comics, a handful of genres were pushed out of the mainstream as a result, including horror and romance – a prominent genre for shojo series. More specifically, the CCA banned portrayals of illicit sexual relations, mandated that romance stories promote the sanctity of marriage, and forbade any sexual “perversions” or “abnormalities” (via History). This meant queerness was censored under the code, thus pushing the LGBTQ demographic to the side along with the female demographic, two demographics that have been catered to for years in shojo and josei series (via New York Public Library).

While the code censored this demographic, underground comix celebrated women like Lyn Chevli, Joyce Farmer, and Aline Kominsky-Crumb (via She Writes Comics). Such as the nature of anything underground, though, said comics were not what the wider public associated with the industry. Superhero comics, on the other hand, were able to keep their foot in the door despite running into issues with the CCA as well.

While horror and romance were once condemned by the CCA, they are making a comeback nowadays, and it’s thanks to independent comics, as well as webtoons. Like in the era of the CCA, storytellers who want to explore these genres go beyond the mainstream to tell said stories. Sure, Marvel and DC have some horror titles, but they are often superhero stories first, with the exception of books like The Nice House on the Lake by James Tynion, Álvaro Martínez Bueno, and Jordie Bellaire.

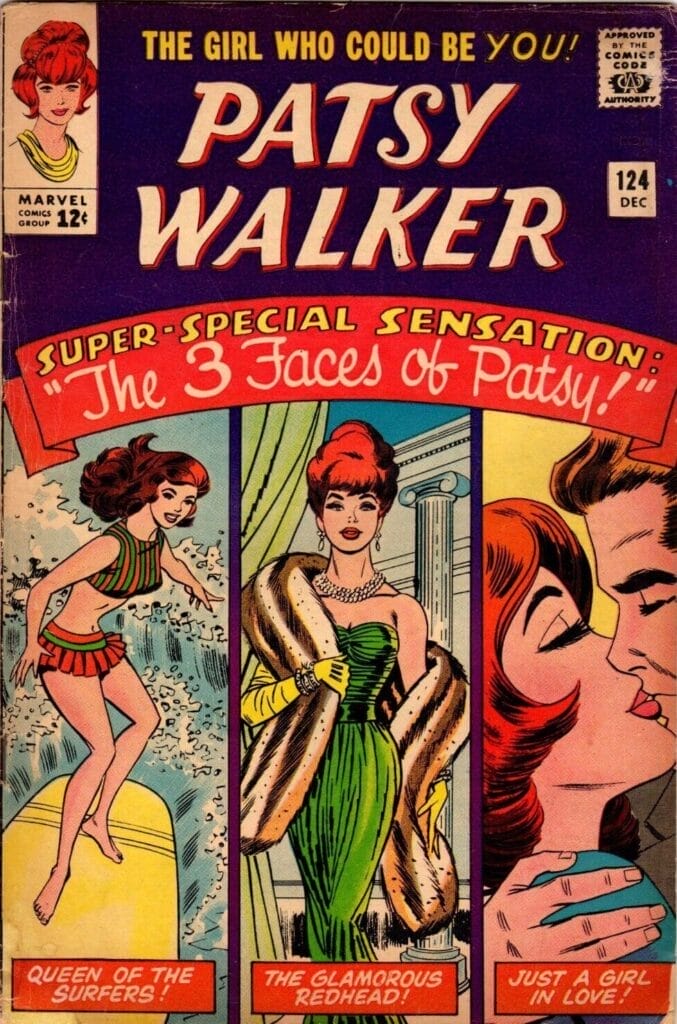

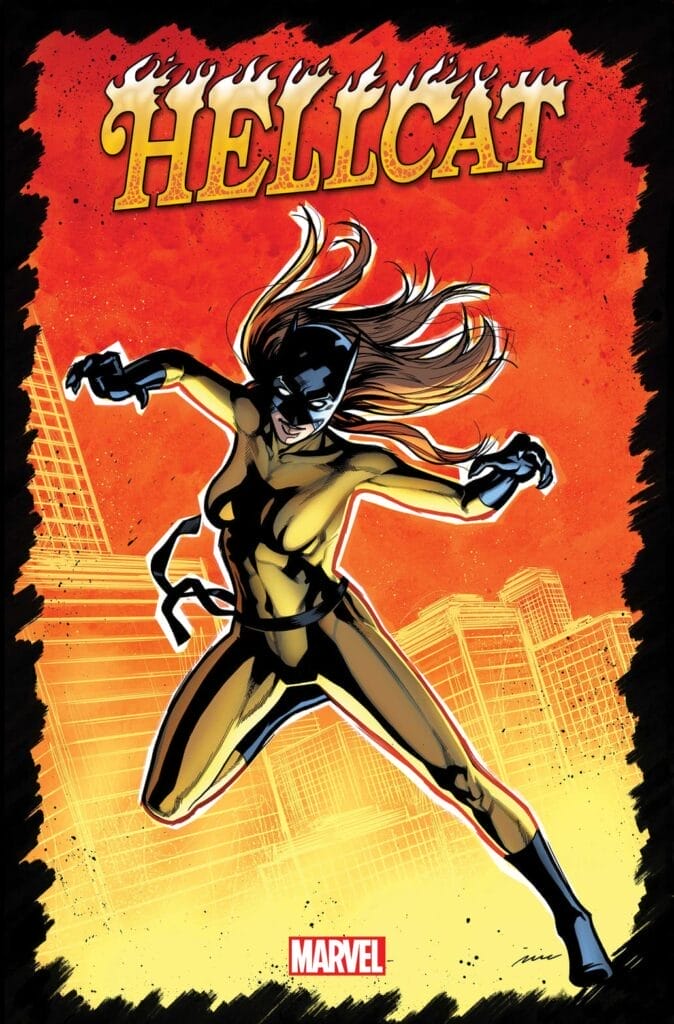

There are also romances in superhero comics, but the love stories are often B-plots. This is unsurprising given how Marvel and DC had to adjust these sorts of genres to appeal to the CCA years ago. For instance, Marvel’s slice-of-life- romance Patsy Walker was reimagined into a superhero comic titled Hellcat during the time of the CCA (via Marvel).

Where Marvel and DC stay true to what’s worked for them for decades, independent comics have a lot more freedom. Along with having a booming horror catalog thanks to publishers like Dark Horse Comics, Boom! Studios, AWA, Image Comics, and more, American comics catering to a shojo demographic have found a home with independent publishers as well.

Titles like Archaia’s Flavor Girls by Loic Locatelli-Kournwsky and Angel De Santiago, Boom! Box’s Save Yourself by Bones Leopard, Kelly Matthews, and Nicole Matthews, and Dark Horse Comics’ Zodiac Starforce by Kevin Panetta and Paulina Ganucheau pull inspiration from magical girl shojo series like Sailor Moon and Cardcaptor Sakura. While it shouldn’t be hard for Marvel and DC to follow in the footsteps of shojo series that have superhero elements, they’re missing the mark where these independent series are taking note.

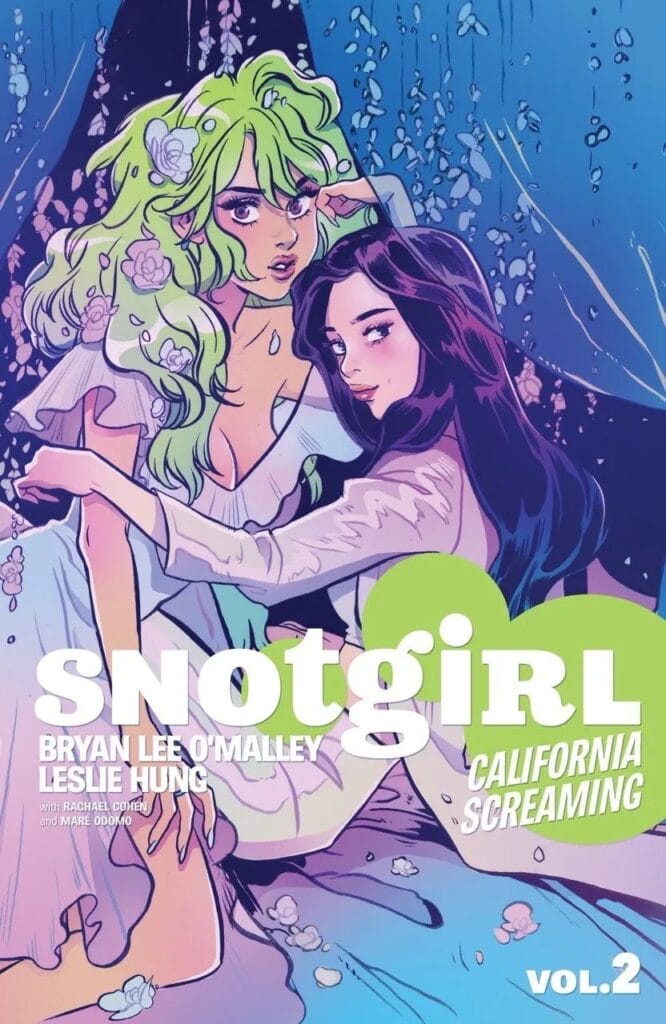

Along with that, independent publishers do a better job at producing queer romance comics and LGBTQ+ stories (via CBR). Oni Press’Chef’s Kiss by Jarrett Melendez, Danica Brine, Hank Jones, and Hassa Otsmane-Elhaou, Image Comics’ Snotgirl by Bryan Lee O’Malley, Leslie Hung, Rachel Cohen, and Mare Odomo, First Second’s Bloom by Kevin Panetta and Savanna Ganucheau, and First Second’s Laura Dean Keeps Breaking Up with Me by Mariko Tamaki and Rosemary Valero-O’Connell are a few titles that feature interpersonal and romantic themes, as well as imagery akin to what’s expected in a shojo series. Along with that, the aforementioned titles all feature queer relationships. Relationships like these are also capitalized on in some shojo and josei series, specifically “girls love” or “boys love” narratives (via Book Riot).

Independent comics cater to the shojo demographic, as well as numerous others that have been pushed to the side thanks to the CCA years ago. Despite this, independent comics have yet to surpass superhero comics in mainstream recognition and periodical sales. Because of this, the public image of comics stays the same. However, other publishers have latched onto another form of storytelling that does right by its female fans and pulls inspiration from shojo and josei series: webcomics.

Heavy Vinyl by Carly Usdin, Nina Vakueva, Irene Flores, Lee Caballero, and Jim Campbell, for instance, is a webcomic from Tapas, but it was re-released as a physical comic thanks to Boom! Studios. Along with that, Heavy Vinyl falls more in line with shojo series than comics from Marvel and DC, as it features a predominantly female cast and focuses on several romantic and platonic relationships. It also explores concepts of femininity, girlhood, and queerness in diverse ways, thus feeding into the feminine aesthetics and themes of shojo series while subverting gender expectations.

On top of webcomics, webtoons – vertical digital comics originating from South Korea (via the Victoria and Albert Museum) – have been adapted into physical books to great success in America, as seen with Lore Olympus by Rachel Smythe. The immensely popular webtoon (1.3 billion views) hit number one on the New York Times’ graphic novel bestseller list with its first volume in 2021 (via The Beat).

Webtoons also are more akin to manga than American print comics, especially when it comes to the wide variety of genres and demographics they include. Along with that, there are numerous webtoons that fall under the shojo banner. True Beauty by Yaongyi (54.9 million likes), Cursed Princess Club by LambCat (21.8 million likes) Boyfriends by refrainbow (23.5 million likes), and Lore Olympus (66.5 million likes) all feel at home with the shojo demographic, and they all have physical counterparts now available.

Along with stylistically and thematically pulling inspiration from shojo and josei series, Webtoon’s primary demographic is young women under the age of 24, according to Forbes in 2021. Webtoon’s audience is the same audience shojo and josei series often cater to. Furthermore, as Forbes points out, Webtoons’ demographics differ greatly from the demographics of periodical comics.

In 2023, 25 percent of comic book readers were baby boomers, and 63 percent of readers were men (via enterpriseappstoday). Working in comic shops in two metropolitan areas – New York City and Los Angeles – most of my regulars are also men. Despite being in cities where one may think the clientele would be more diverse, I have had more than my fair share of encounters with male customers who had disparaging comments about me being a woman in comics, including several who did not believe I read the periodicals or classics. Don’t get me wrong, I adore working in a comic shop and have a lot of love for my amazing customers – men and women alike. However, I can’t ignore how a majority of my interactions – whether positive or negative – are with men.

Women and the queer community have historically been censored or erased from mainstream American comics thanks to the CCA. While the CCA ended over a decade ago (via Book Riot), the face of the industry – superhero periodicals – stays the same, as does its primary demographic – men.

As a result, many outside this demographic go beyond superhero periodicals for their comic fix. While some turn to underground comix, independent comics, or webcomics, others turn to manga. Afterall, shojo series have welcomed women readers for decades. While there has been progress in regard to welcoming more women into superhero periodicals, it’s not enough, as evidenced by the ratio of male readers to female readers, as well as the disappointing sales numbers for American superhero comics nowadays.

Why Do Superhero Periodicals Need to Cater to Shojo Readers?

Despite superhero comics being the face of the industry, this does not mean they are killing it in sales. In 2022, The Beat reported that superhero comics were only 14 percent of graphic novel sales in North America. Meanwhile, manga was 45 percent of sales. One can then assume the remaining graphic novel sales went to independent graphic novels or physical print copies of webtoons, both of which cater to a shojo demographic to varying extents.

What’s more surprising is that superhero comics should be the American equivalent of shonen series, the biggest-selling books for manga in 2023 (via IGN). After all, both traditionally target the same demographic; however, where superhero comics maintain their male fanbase, shonen series are broadening their demographics to include men and women, as addressed earlier.

Where manga, webtoons, and independent comics have leaned into a broader demographic, American superhero comics have not, and it’s hurting them. It’s gotten to a point where publishers like DC and Marvel are trying new tactics to maintain their hold on the American comic industry.

DC, for instance, has taken notice of the success of webtoons, as well as shojo-like comics. One of the biggest stories on Webtoon (105.3 million views) is none other than Batman: Wayne Family Adventures by StarBite and CRC Payne – a slice-of-life reimagining of Batman and co. DC Comics has a handful of other webtoons – Vixen: NYC by Jasmine Walls and Manou Azumi and Zatanna and the Ripper by Sarah Dealy and Syro – as well.

DC also has a successful young adult line of graphic novels that are akin to shojo series in plot and style. A majority of these YA titles are heavy on the romance, feature coming-of-age themes, incorporate some of the shojo visual elements addressed in this essay, and have a fair amount of titles featuring both male and female leads (via Barnes and Noble). They are also separate from the main continuity, so they are great starting places for new readers, but that is the catch.

DC Comics is taking steps in the right direction to broaden its demographic through YA graphic novels and webtoons, but these stories are separate from the periodicals that are the face of the publisher. On the Webtoon front, these comics will likely be seen as webtoons first, comics second. After all, they are released on Webtoon months before they are available for purchase in comic shops, and they are free to read online.

Meanwhile, the YA graphic novels have been popular (via Penguin Random House), but most of them are stand-alone outside of a few series, like Kami Garcia and Gabriel Picolo’s Teen Titans. They are also released much more sporadically than periodicals, so the chance of them instilling a readership that returns to their local comic shop every week is smaller.

As for Marvel, they lack a line dedicated to YA graphic novels. Meanwhile, their digital comics are similar to what’s represented on the shelves, so it’s a lot of the same thing but in a digital package – one that comes at a price ($9.99 a month), unlike Webtoon. There are a few exceptions that break the mold like It’s Jeff! by Kelly Thompson and Gurihiru, but those are rare and outside of continuity.

Instead of committing to broadening its demographic on a large scale, these powerhouse publishers provide niche substitutes for comic readers who feel overlooked by the medium. On the digital front, there is a lack of incentive to go to a comic shop and pick up these titles. As for YA graphic novels, it’s clear these titles are separate from continuity. Instead of treating the shojo demographic as an equal to their usual demographic, these publishers other them.

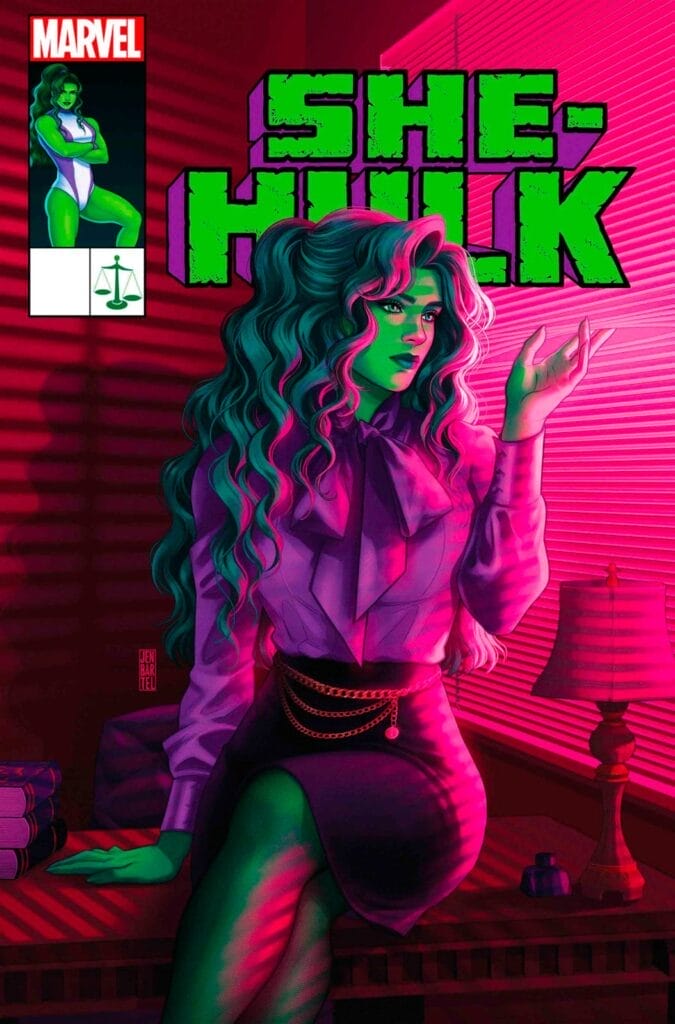

Marvel and DC have taken steps in the right direction through webtoons, YA graphic novels, and a handful of periodicals – Fire & Ice: Welcome to Smallville by Joanne Starer and Natacha Bustos, and She-Hulk by Rainbow Rowell, Roge Antonio, Luca Maresca, and Rico Renzi. However, these are outliers in the grand scheme of the superhero machine. Therefore, it others readers who are interested in comics like these – comics targeting a shojo demographic.

If superhero periodicals didn’t control the public perception of American comics, this would not be as much of an issue. Independent publishers and webcomics are catering directly to the shojo demographic without treating them like outliers, and there are hundreds of stories to check out from these publishers and outlets. However, as long as superhero periodicals continue to be the face of the industry, it’s on them to prove to new readers that American comics at large are not a boy’s club.

There are so many wonderful women in American comics – on and off page. There is also a female fanbase ready for more comics dedicated to them, but the superhero periodicals – the books controlling the industry’s image – fail to welcome this demographic fully.

Manga, on the other hand, sees massive international success and welcomes said demographic with open arms thanks to shojo series. Even books that do not traditionally target this demographic have put in the work to make women feel welcomed by pulling inspiration from shojo series in a variety of ways – intentional or not.

On a smaller scale, the American comic industry does this, as seen by the numerous independent titles. The industry is also aware that other forms of comic storytelling, like webtoons, have found success by catering to a shojo and josei demographic

Unfortunately, the public perception of American comics often falls on Marvel and DC. Outside these books being a majority of what’s on the shelves, they have found their way into the mainstream thanks to film, television, and video game adaptations. There have been attempts to cater to a shojo demographic from these publishers, but said attempts are often outliers. Meanwhile, their main continuity still caters to the same demographic it’s catered to for decades, leaving new female readers behind.

With manga surpassing American comics sales-wise, the heavy hitters of the industry need to take note of how to welcome new readers. Including the shojo demographic like manga, independent comics, and webtoons is one way the publishers controlling how we view the American comic industry can do just that.