Cover image: La scintilla dell’amore by Kuroda Sakaki (Kappa Edizioni, 2006)

A girl is out at the newsstand next to her building, buying some magazines for her mother and a newspaper for her grandfather. The air is cold, she shivers in her coat as she just so quickly browses the small comic book section the kiosk offers: a lot of Tex, which she finds boring, but also a lot of Dylan Dog, whom she finds kind of hot. There are some Japanese manga too— she has been a fan for a couple of years, so it is quite handy to have it there. Plus, they’re dirt cheap!

Her eyes stop on one peculiar title called New York New York by Ragawa Marimo. It’s November 1999 and Panini Comics has just published Italy’s first BL manga.

Italy has been many things throughout its history. However, “consistent” is not one of these things. The country, my country, is known for being volatile, and Italians for being quick to change their heart on something—with either negative or positive outcomes.

So, it comes as little wonder that Japanese media has been imported for as long as most of us can remember, at least since the second post-war boom of the ‘60s, with high praise, too. Though, at the same time, it was treated like a plaything for children.

Anime was relegated to child-friendly timeslots on TV, heavily censored and toned down to suit the tastes of kids ranging from six to fourteen years of age. Most anime of the ’70s weren’t as heavily edited as those that got the chop throughout the ’80s, ’90s and early ’00s.

I, myself, mostly grew up with name-changed, cropped, and often altered anime, until MTV got ahold of it in 1999 with the MTV Anime Night segment. This aired every Tuesday at 9 PM and showcased more “adult” (namely, Trigun, Cowboy Bebop, Full Metal Panic, etc.) shows without any changes, aside from dubbing.

Manga took a little longer to reach the boot-shaped peninsula, but in 1990 we got Fist of the North Star, which kickstarted a slow-building phenomenon of Italian nerd subculture. Manga were often ignored by censorship, possibly because younger kids weren’t talking about comics as much as they would with cartoons.

Furthermore, Italians haven’t been reading much for the past three decades, in general. Thus, whenever you would pick up a comic, may it be Italian, French, American or Japanese, it usually didn’t feature any meddling.

Among those kids who did go out of their way to read manga and get passionate about it, we will meet an even smaller part of the already (then) small Italian nerd subculture: yaoi fans.

Also known in the Italian slang of the late ‘90s and early ‘00s as yaoiste (plural feminine; singular feminine or masculine would be yaoista). The word comes from the union of the term yaoi and the suffix -ista, which is usually reserved for religious practitioners such as buddhista, Buddhist, or shintoista, Shintoist.

We’re going for a ride.

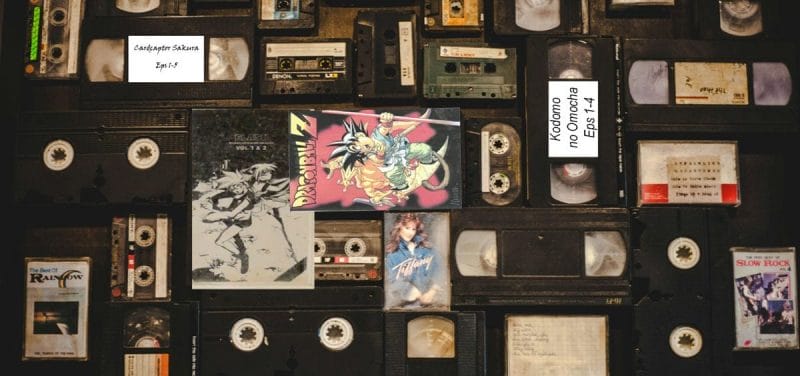

At the cusp of the new millennium, the BL genre officially touched the coasts of Italy with the above-mentioned title New York New York. However, a large number of teen girls and twenty-somethings were already getting interested in this subgenre of shōjo manga from Japan, thanks to the budding world wide web and the small assortment of anime titles that had already been imported since the late 1990s like Kizuna and Ai no Kusabi).

These pioneers browsed the internet in search of community. They bonded over fan art and dōjinshi found on the internet, as they tried to escape the toxic social climate of the early noughties. Nerd spaces were also minefields for girls or young women who wanted to interact with any type of geek media, so connecting over something that felt like a “safe space” for them (and later, queer readers) seemed almost natural.

Much like in Japan in the ‘70s, the term yaoi began to spread throughout the Italian side of the internet as a general term for stories involving boys loving boys, helping a younger audience of girls to get accustomed to sex and sexuality—maybe even their own.

In a traditionalist and close-minded society like Italy’s, most girls weren’t allowed the same sexual freedom as their male peers and, in comparison, their reading preferences were also put under higher scrutiny. So, the fans enjoyed it in secret, scared of getting caught reading something explicit more so than something containing queer characters.

The stigma of liking erotica, as a woman, was so overbearing that most fans were living parallel lives. Online, they were thriving on dedicated forums or websites like yaoitalia.it, shared with like-minded lovers of BL comics, appreciating slash fiction on the Italian equivalent of fanfiction.net, also known as EFP (efpfanfic.net, still active) and, sometimes, drawing fan arts or original works themselves. Famous examples included the BL circle “Le Peruggine” or the birth of Teke, a small indie publisher. Offline, though, they were living their daily lives, buying “regular” manga at best, or hiding those, too, at worst.

Most people approaching BL titles at the time were consuming almost every single piece of relevant media they could find. The number of originals available in comic shops was limited, almost exclusively imported by Kappa Edizioni—now known as KappaLab—and Flashbook. So were their anime counterparts: many will remember Gravitation or Sukisho. Though, the king that took the crown was Junjō Romantica, arguably the first “mainstream” BL anime title to reach most Italian fans.

In the whole decade between the year 2000 and 2010, only thirty-nine BL manga and manhwa titles were imported and officially translated to Italian; the fans were starved for more content. Forums grew at an exponential rate, thus “yaoista” started appearing in online spaces as early as 2006—until it also migrated onto the convention sphere.

As the general “otaku” subculture was taking roots in the hearts of many Italians, yaoi fans would gather both at smaller and bigger anime conventions, especially at the main event on the whole peninsula: a fair called Lucca Comics & Games. The event is hosted every year in a small medieval city in Tuscany called, well, Lucca.

BL dōjinshi resellers, illegally printed images on bootleg merchandise, actual original volumes, and countless cosplays accompanied these women whenever they met. Rome, Milan and Naples were huge hubs for offline meetings of yaoiste, with even a small store called “Neko Shop”, based in Rome, that would host weekly anime screenings and sell dōjinshi or BL manga— even made by Italians themselves!

And here we are. It’s 2012, and we are witnessing the second generation of young Boys’ Love fans.

A new era welcomes the world as the internet shifts from web 1.0 to web 2.0, and social media begins to take root in society. Facebook and Wattpad will play a pivotal role in the growth of the Italian yaoi/BL fandom, not to mention the spread of both original and fan content with a focus on m/m relationships.

Facebook groups dedicated to the genre began to replace traditional forums, and EFP was slowly losing traction, substituted by Wattpad, an app for writing short stories, readily available on our new little trinkets called “smartphones.” In just two years—2011 and 2012—Italy had already imported and translated 23 BL titles, and many girls were now seeing them appear in comic book stores across the country.

Still, BL and its fans continue to be heavily stigmatized, though, by a greater society that didn’t understand such a specific type of fiction. Underground spaces, a usually very territorial field for male (cisgender, heterosexual) nerds and otaku, also harshly criticized BL content and mocked yaoi fans, considering the genre as the derogatory “erotica for women,” or as straight-up trash.

Much of the repulsion Italian male nerds felt toward BL was related to Italy’s (still) deeply machista, queerphobic and patriarchal society. Seeing two androgynous characters acting in a “non-heterosexual” way was challenging the accepted “status quo” definition of masculinity.

The male-dominated nerd space felt attacked by such a small group of women, who were now putting their feet down by showing their love for BL media, without any shame, also in virtue of their young age. Problems arose once yaoi fans felt as much an outcast as actual queer people, sometimes behaving inappropriately, both offline and online.

The fetishisation of gay men was, and still is, a problem that runs high among BL fans. During that period especially, many of the popular stereotypes (rape, sexual assault, unhealthy BDSM practices, etc.) seen in BL comics or dōjinshi were regarded as “actual gay behaviour”, further alienating Italian queer readers, especially gay men.

To this day, Italy struggles with LGBTQ+ rights. Civil partnership happened in 2016, though adoption is not allowed, for example. In some ways, the landscape is a mirror image of Japan. Regardless, publishers began releasing more and more titles to stores to please an ever-growing fandom that peaked around 2015-2016, and ultimately stabilized around the end of the 2010s.

It was during this period that manga prices also started to inflate. Where an average volume in 2009 would cost around €3, the average price quickly jumped to €8, regardless of the quality of the book itself or its translation. At the same time, other publishers started to pick up on the lucrative side of the phenomenon: it’s capitalism at its best, baby!

The new big hits pushing BL as a conversation starter in high school corridors, and among peers in University classrooms, though, were now coming mainly from Korea, exploding in demand with the translation of Killing Stalking back in 2017, and later with Webtoon titles like BJ Alex, Bloodbank, or On or Off.

BL’s popularity continued building in popularity until the COVID-19 pandemic, when the genre skyrocketed into mainstream consciousness alongside mainstream manga, thanks to Italy’s three-month-long mandatory lockdown. Platforms like Instagram and Tiktok are now where the fun’s at. Contemporary teens share their passion with older fans, leading publishers to import even more titles.

The new yaoista is now a little different; they prefer the imported word “fujoshi” (or “fudanshi/fujin”) and are generally more aware of Italy’s queerphobic climate, but still suffer the scorn of their male peers.

Month after month, new titles are distributed by publishers, greatly supporting the rediscovery of women and queer people making money go round. Cisgender, heterosexual boys and men still actively (and very vocally) show their discomfort for the mere existence of these comics on the shelves of their precious shops, though, often by commenting on their favourite publisher of choice’s Instagram account.

The contemporary, 2022 Italian BL fandom counts a lot of different people, may they be a young bisexual sixteen-year-old girl, or a thirty-five-year-old non-binary person: the times are changing even in the land of saints, poets and sailors. It’s a very peculiar transformation, and one I want nothing more than to witness.

Though, back in the 2000s, we could encounter Italian comics that depicted m/m relationships labelled as “yaoi”, nowadays, most authors portray their queer characters as conscious of living in a specific society and in a specific country: Italy.

Plus, publishers are way fonder of the highly-regarded label of “graphic novel”: being an English loan word, it sounds cooler and it doesn’t remind people of “comics” (fumetti), still considered lowbrow literature. A clear example is In Italia sono tutti maschi (non-literal translation being “In Italy they’re all real men”) by Luca de Santis and Luca Colaone, which shows the tragedy of being a gay man under Fascist Italy in the late 1930s.

Flavia Biondi, Fumettibrutti, Giopota, Giulio Macaione and many other artists are depicting slice-of-life stories that often focus on the struggle of being queer in Italy: a clear distance is put between the fantasy storytelling found in BL titles from Japan or Korea.

BL manga are famous around the globe, that’s for sure. However, Italy holds the genre dear to its heart much like its motherland of Japan, especially because it gave girls and women a stronghold to understand themselves. Also, it seems that, in recent years, queer readers make up at least half of the audience!

Though, the country still has a lot of problems in handling the genre. Publishers often hide a veiled homo/queerphobia behind a layer of plastic that surrounds most BL titles sold on shelves, whether they contain erotica or not, while ecchi/allusive works, like Italian comic artist Milo Manara’s, or dark titles, such as Berserk or any work by Maruo Suheiro or Itō Junji, are left completely open for any child roaming a book shop to open.

As usually, this oddball of a country is full of contradictions, as we see more and more socially aware BL or BL-adjacent works are being made and also translated to Italian, like Our Dreams at Dusk or My Son is Probably Gay, marking an attempt to reach out with non-manga fans, too.

2020 also marked the start of a new series in major-publisher’s Star Comics roster simply called “Queer”, counting for a handpicked number of titles from the BL, GL and manga world at large, aiming to be more inclusive (such as Our Not So Lonely Planet Travel Guide and Boys Run the Riot).

So, surely, Italy’s love for BL is very much like a telenovela: troubled, problematic but, above all, passionate.