Thank you to Mark McDonald for the Patron article request!

Editor: Samantha Ferreira

In 1983, Lupin The Third made his North American TV debut on WTBS.

Well, not quite – the rascally thief wouldn’t get his crack at home video success in the US for a few more years. But viewers of the short-lived game show, Starcade, could get an early taste of his antics thanks to Stern Electronics. That year, the arcade titan released Cliff Hanger: a cutting-edge laserdisc game that stitched together footage from Castle of Cagliostro and Mystery of Mamo.

Released in the wake of Don Bluth’s arcade blockbuster, Dragon’s Lair, Cliff Hanger capitalized on the short-lived boom of laserdisc games. It relied on the strengths of Hayao Miyazaki and Soji Yōshikawa’s artful productions to sell the game, with vibrant attract screens that were unlike anything else in American arcades at the time.

(Well, outside of Dragon’s Lair.)

Cliff Hanger is often cited alongside both Lair and Space Ace as the third major pillar of animated laserdisc gaming. There’s no denying its importance – the game played a major hand in popularizing Lupin III and anime in general, even appearing in The Goonies. But all three titles were preceded by an ambitious Data East title that launched one year earlier – Bega’s Battle.

Bega’s Battle was the very first video game to utilize anime cutscenes. Unlike the games that would go on to popularize the genre, the 1982 title blended actual shoot-’em-up gameplay with animated storytelling. It’s mostly remembered as a curio in the United States, though, and had a relatively low penetration rate outside of Japan.

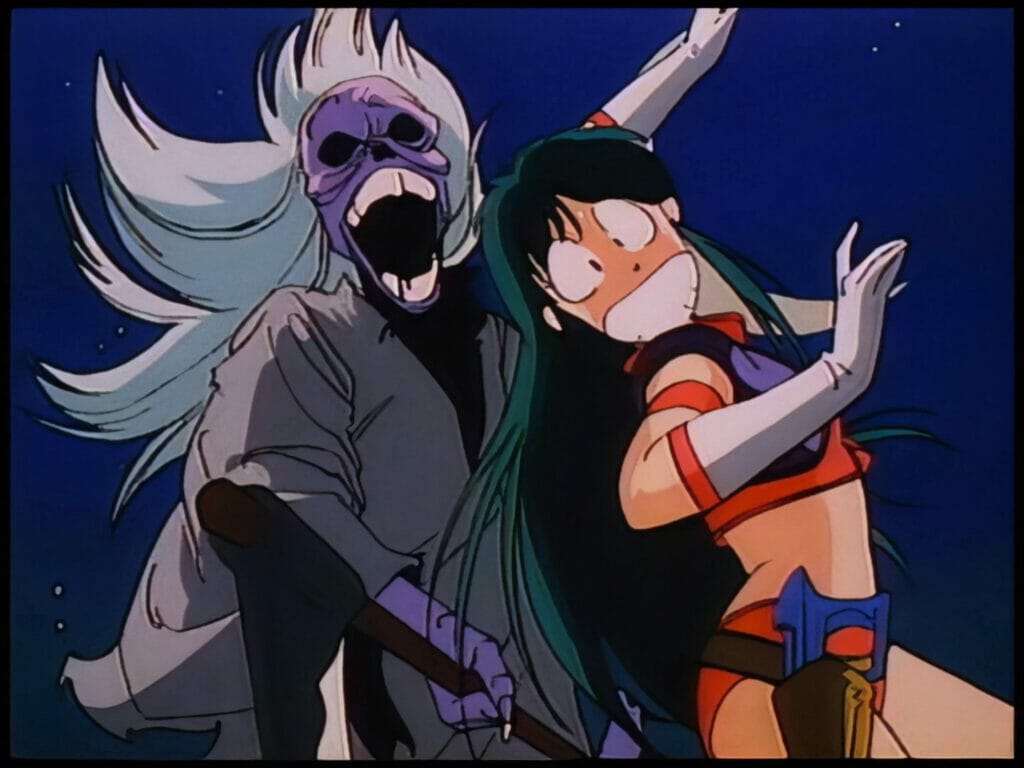

But in Japan, it was a different story. Bega’s Battle is drawn from Genma Taisen (known as Harmagedon in America), a smash-hit series at the time. In 1967, the Kazumasa Hirai and Shotaro Ishinomori collaboration ran in Kodansha’s Weekly Shōnen Magazine for two volumes before getting canned prematurely. The 1970s were kinder, though, as the franchise enjoyed a second life in a successful run of novels. By 1983, it had been a pop culture fixture for a combined fifteen-plus years, and cemented itself as a landmark work of Japanese sci-fi.

That year, Kadokawa tapped Madhouse and esteemed director Rintaro for a sprawling two-plus hour animated adaptation. Rintaro was hot off the box office success of his two Galaxy Express 999 films, which made him a prime candidate for the science fiction project. And while contemporary appraisal has been largely unfavorable, the picture tends to be remembered as a classic among Japanese fans who grew up with it. Like an Aliens or Jurassic Park, it was supported by an aggressive multi-media blitz that ensured it glommed up some stock of cultural cachet.

No small amount of the project’s success was due, in part, to Data East’s tie-in. Every in-game and interstitial cutscene is drawn from the smash-hit feature, which opened in the same month – March 1983. The Genma Taisen game gave fans a chance to experience the film ahead of its home video release. The onboard Sony Laserdisc player ensured that they got prettier, clearer footage than the contemporaneous VHS, to boot.

Apart from being a decent, if basic shooter, Genma Taisen was a massive advertisement for the highest-grossing animated film in Japan that year. Taking that into consideration, then, it makes sense that the game was one of the most widely played titles in Japanese arcades at the time. By November 1983, Game Machine reported that Genma Taisen was still the third-most played game in Japanese arcades – almost eight months after its launch.

Its primary competition? Astron Belt – another hugely popular laserdisc game that used footage from, among other things, Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan. Sega’s hit was revolutionary for the time, as it used live footage as the backdrop to a rudimentary 2D game. It was, in fact, the first commercial – not to mention commercially successful – laserdisc game. Data East was looking Sega square in the eye with their competitor – ready to up the ante.

Whether you know it as Bega’s Battle or Genma Taisen, Data East’s title is more influential and important than it gets credit for. In the rush to make a splashy piece of promotion for a blockbuster tie-in, the developers inadvertently predicted a trend. It’s the first game to ever use distinct animated cutscenes between gameplay segments, predating the trend of fully rendered FMV animatics. Because of that, it could be argued that Bega’s Battle birthed the pre-rendered cutscene as we know it.

In Japan, Genma Taisen was a landmark success that helped usher in a new era for arcade gaming. It was aided by an established media franchise and a blockbuster film. In America, however, the game flopped. Most of the ~700 Bega’s Battle cabinets were converted into Cobra Command machines by the following year. These days, the cab is exceedingly rare in its original form, with an estimated ballpark value of over $5,000 USD.

(Of course, because so few are being passed around, there’s no telling how much the next one will crop up for – or if one will.)

It’s in the success of Genma Taisen and the failure of Bega’s Battle that Cliff Hanger managed to succeed. Dragon’s Lair made laserdisc games stick with American players by removing gameplay altogether, outside of timed button presses. Cliff Hanger emulated this model, leaning on the Lupin footage to entice players.

Because Bega’s was such a tremendous failure in American arcades, too, Stern had an edge on Data East when it came to using anime as a stylistic choice. Most Americans in the Reagan years had limited, if any, knowledge of anime outside of a select few properties. For some, this might have been their first (or only) exposure to anime outside of, say, Speed Racer or Robotech. In that context, Cliff Hanger’s immediate appeal makes sense. Dragon’s Lair was drawn from American technique and tradition, making it more familiar to generations raised on Disney fairy tales. Cliff Hanger, meanwhile, was a modern-day blockbuster, boasting unique art most contemporary players had never seen.

But even that success was short-lived. Popular dictum states that laserdisc games died off within a year, with few developers able to find new ways to iterate on them. That isn’t entirely true, though. 1984 saw the release of Taito’s Ninja Hayate—which boasted original animation from Toei—and Universal’s generally ill-received Super Don Quix-Ote. Both titles iterated on the ideas present in Dragon’s Lair, albeit to much less success.

The following year, Toei and Taito teamed up for Time Gal. While it was another riff on the already-aging mechanics of Dragon’s Lair, Time Gal was notable for its beautiful original animation, as well as for boasting one of the industry’s earliest human female protagonists. It’s best described as a Project A-Ko alike, in the sense that it’s a broad pastiche of—and love letter to—sci-fi of the era. At the time. it was a hit, and according to anime and gaming historian Mike Toole, Taito even changed their mascot to the titular Gal for a spot.

But it wouldn’t last. As home console heavy-hitters like Nintendo and arcade juggernauts such as Capcom redefined the gaming landscape, laserdisc games quickly fell out of vogue. Even so, their impact would be felt in Japanese development well into the ‘90s. As home computing technology improved, it became easier to compress video and play it back on a variety of devices. CD-ROM was a boon to the medium, and in the early ‘90s, hardware manufacturers like Sega and 3DO tried to explore the medium, albeit with little financial success.

These too, though, were important years for anime’s involvement with video games. One of the earliest Sega CD titles, in fact, was Time Gal. Moreover, Sega itself tapped anime studios for pre-rendered animatics in their own titles. The most well-known instance of this is arguably Toei’s opening, closing, and interstitial animations for Sonic CD. In particular, the opening sequence—directed by Sonic co-creator Naoto Oshima and set to a song penned by Orguss theme performer Casey Rankin—has long been an object of cult fixation in the Sonic fanbase.

From the mid-1990s onward, anime cutscenes exploded into video games, thanks to the advent of the Sony PlayStation. The console was a runaway global success, thanks to impressive 3D visuals and a diverse library of games. This meant that the dominant system had a CD drive, which opened the door for developers to innovate on new and exciting ways to work anime into their titles. And while it was more limited, the Sega Saturn—popular in Japan but a tremendous Western failure due to general mismanagement—also boasted a number of titles doing the same thing. Games like Sakura Wars, Lunar and Thousand Arms introduced unique anime cutscenes into the story, creating organic narrative tapestries between the gameplay and the plot.

Post-2000, anime in video games wasn’t a novelty anymore – it was a thriving and viable artistic choice. From the PlayStation 2 to now, entire franchises have built themselves around lush and expensive anime cutscenes to sell their aesthetic. This goes up to as recently as titles like Persona 5, which tells a good portion of its story through gorgeous anime sequences courtesy of CloverWorks. Even Nintendo has tapped into the practice in the past decade, as they’ve commissioned the likes of Studio Khara to work on their Fire Emblem series.

In 1983, it was a risk to release Genma Taisen. These cabinets were expensive to build and maintain, not to mention the fees involved with the prestigious license. It was even riskier to reskin it and release it as Bega’s Battle to an audience totally ignorant of the source material. But because of Data East’s early risks—made in hopes of capitalizing on Sega’s success with Astron Belt—an entire industry was changed.

Data East knew anime and games would go together. They were just a few years too early.

Sources

- “Bega’s Battle.” International Arcade Museum.

- “Bega’s Battle” Dragon’s Lair Project.

- Ciolek, Todd. “Column: ‘Might Have Been’ – Time Gal”. GameSetWatch

- Exidy’s Arcade Price Guide.

- “Game Machine’s Best Hit Games 25 – アップライト, コックピット型TVゲーム機 (Upright/Cockpit Videos)”. Game Machine. No. 223. November 1983.

- Sevakis, Justin. “Buried Garbage – Harmageddon.” Anime News Network.

- Starrcade #103 – Cliff Hanger. YouTube.

- Toole, Mike (January 8, 2017). “The Mike Toole Show – The Amazing World of Anime Arcade Games”. Anime News Network.